The Etruscan Curse: Ghosts and Imperial Splendor in Lucius Verus’s Vanished Villa

Rome, Italy

The amnis Tutia or Tutia River (meaning "Safe River") was an ancient stream that, three thousand years ago, was significantly richer in water than it is today. Originating from the hills of Insugherata and Monte Arsiccio, it flowed along the valley floor until it emptied into the Tiber near the Via Flaminia.

In the Middle Ages, it bisected an estate – consequently named 'Acqua Traversa' (Water Crossing) – and crossed the ancient Via Cassia, three miles from Rome, and the Via Flaminia, about four miles from Porta Flaminia. We know that the estate, traversed in Etruscan times by the ancient Via Veientana, became the property of the Borghese family between the 16th and 17th centuries. The Borghese were a noble family originally from Siena, recently relocated to Rome when Camillo, their firstborn, was born.

Indeed, his father Marcantonio was a consistorial lawyer who had chosen Rome to tie his fortunes to those of the Papal Curia. He dedicated all his resources to preparing the first of his seven children, Camillo and Orazio, for high-level careers. Camillo (1552-1621), after graduating, first worked as a lawyer (following his father's footsteps) until he chose an ecclesiastical career. Within less than thirty years, he became Pope Paul V (1605-1621). A great admirer of Caravaggio, he commissioned numerous works in Rome, such as the Belvedere Fountain and the restoration of the Trajan Aqueduct.Excavations sponsored by the Borghese during Paul V's pontificate were carried out on the Acqua Traversa estate in search of antiquities. Numerous Roman-era artifacts were discovered, enriching the antiquities market with marble pieces now housed in museums worldwide.

Portrait of Pope Paul V by Caravaggio (1571–1610), 1605 circa.

The discovery of a fine bust of Lucius Verus (who reigned alongside his adoptive brother Marcus Aurelius from 161 AD until his death) immediately led to the belief that his imperial villa existed on this site. This was confirmed by the testimony of Iulius Capitolinus in the Historia Augusta:

Villam praeterea extruxit in via Clodia famosissimam, in qua per multos dies et ipse ingenti luxuria debacchatus est cum libertis suis et amicis Paridis, quorum praesentiae nulla inerat reverentia, et Marcus rogavit, qui venit, ut fratri venerabilem morum suorum et imitandam ostenderet sanctitudinem, et quinque diebus in eadem villa residens cognitionibus continuis operam dedit, aut convivante fratre aut convivia comparante.

Furthermore, he built an exceedingly notorious villa on the Clodian Way, and here he not only reviled himself for many days at a time in boundless extravagance together with his freedmen and friends of inferior rank in whose presence he felt no shame, but he even invited Marcus. Marcus came, in order to display to his brother the purity of his own moral code as worthy of respect and imitation, and for five days, staying in the same villa, he busied himself continuously with the examination of law-cases, while his brother, in the meantime, was either banqueting or preparing banquets.

Historia Augusta, vol.I, 8.8. The Life of Lucius Verus.

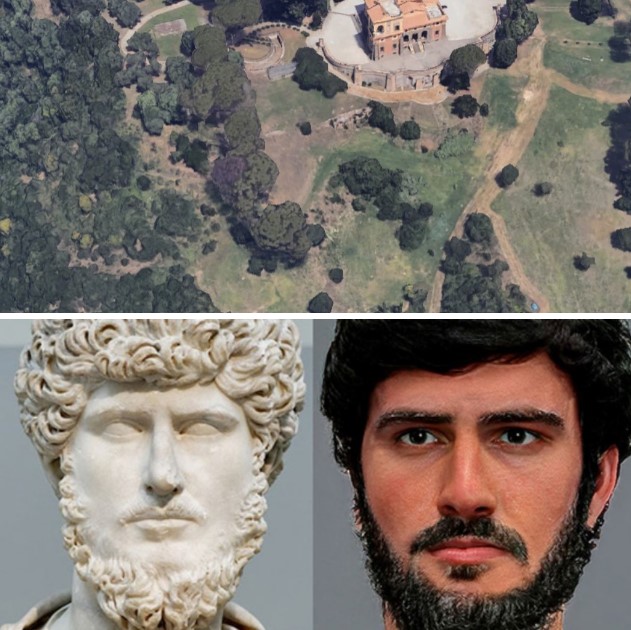

Villa Manzoni built atop the still-visible ruins of Lucius Verus' imperial villa, with a 3D facial reconstruction.

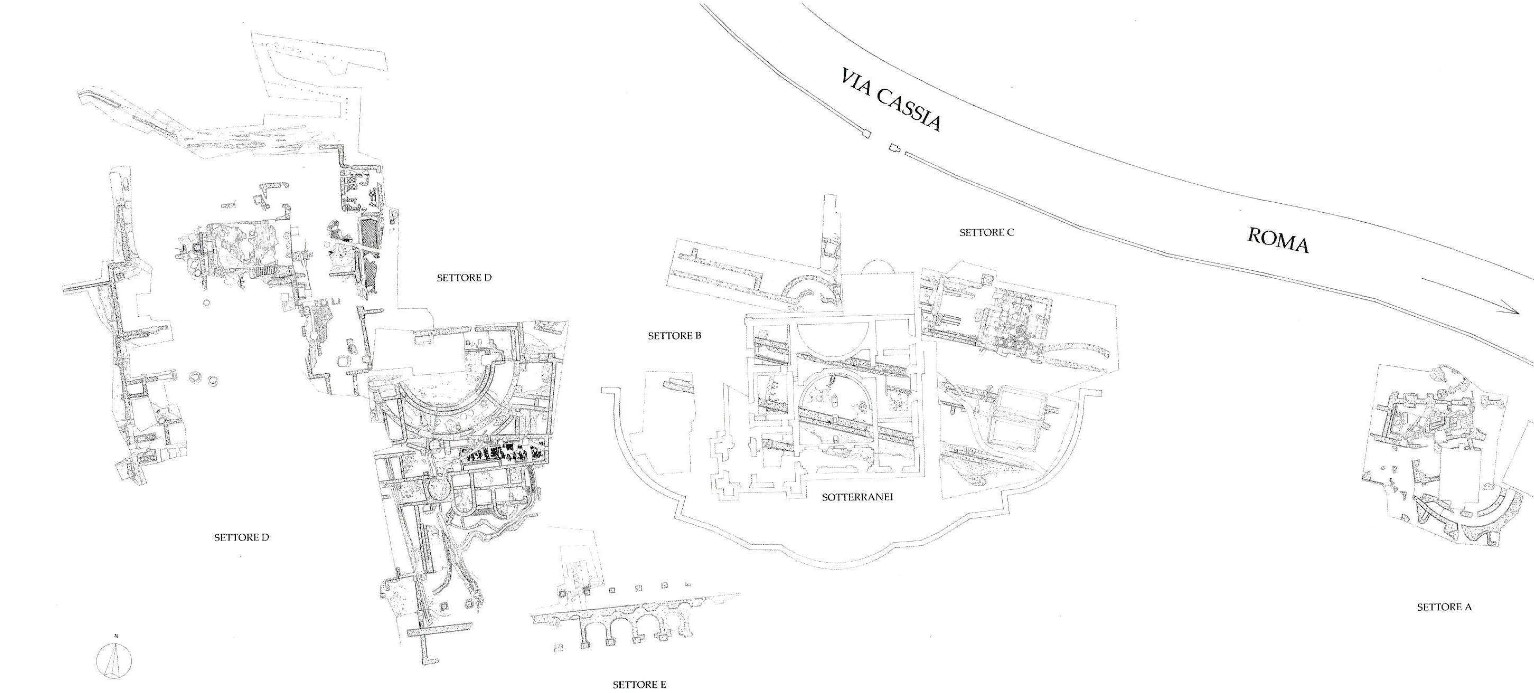

The biographer of Lucius Verus documented, with these words, the presence of a residence of considerable size and magnificent appearance built by the emperor at the fifth mile of the Via Clodia (which coincides with the Cassia in its initial stretch) in the 2nd century AD, in the locality of Acquatraversa. It stood on a hillock offering views stretching to the center of the city and overlooking the valley (89 m above sea level is the highest point to the northwest). This complex follows the hillside slope from north to south, arranged on terraced levels: the higher areas occupied by gardens and reception rooms, and the lower areas by private baths.

Ultimately, few sites along the consular road can be justifiably included among imperial properties based on the scale of their structures and the richness of their artifacts; thus, the remains are now unanimously recognized by scholars as belonging to an imperial complex.

While today the villa lies on the left side of the road, in antiquity it was on the right, because the ancient Via Cassia ran straight beyond the Acqua Traversa ditch, traversing the valley floor and reconnecting with the modern Via Cassia Nuova near the so-called 'Tomb of Nero'. Unlike other consular roads where sections of the original basalt paving are visible in multiple points in Rome's immediate suburbs, the route of the ancient Cassia, at least up to the sixth mile, is documented by the presence of funerary buildings and simple tombs, mostly found during opportunistic excavations.

The author recalls that Marcus Aurelius stayed at Lucius's villa for five days, continuously administering justice: cognitionibus continuis operam dedit.

Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, British Museum.

It was 166 AD when Lucius Verus returned triumphant from the eastern campaigns, where he had been sent by his brother Marcus Aurelius to confront threats from the Parthians on the empire's eastern flank. Between 166 and 169, the year of his death at Altinum during a military expedition, Lucius Verus stayed in Rome and likely initiated the construction of his lavish residence during this period. Pre-existing structures were supplanted and incorporated into a new complex occupying the entire flat area to the north, with some reused and others decommissioned. Access to the late 2nd-century residence was via a side road ascending from the Via Cassia in the valley floor. It comprised monumental structures, residential quarters opening onto green areas, service rooms around a pre-existing cistern, and a balneum (bath complex) in the southwest area.

In the 17th century, discoveries included a Venus and a lead conduit, 2 feet and 4 inches wide, weighing over 40,000 pounds; nine busts, mainly of the Antonines, and various coins also pertaining to them; a finely worked herm of Heracles; a seated female statue; and a head of Marcus Aurelius. Later finds included two magnificent colossal busts of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus; and finally, alabaster columns and other monuments. The busts were sold by Camillo Borghese in 1807 to Napoleon and are now in the Louvre Museum. Two of these busts (nos. 1170 and 1179), attributed stylistically to a posthumous execution, represented, prior to excavations conducted between 2005 and 2009, the only evidence of the villa's use after 180 AD.

In the early 19th century, through the mediation of Giovanni Pierantoni, restorer for the Vatican Museums, other sculptures entered the new arrangement of the Gallery of the Candelabra and the New Wing of the Chiaramonti Museum. These included a male statue, a satyr statue, a statue of a boy "nut thrower" (all in white marble) dated to the mid-2nd century AD, as well as marble capitals and alabaster columns from excavations that the English collector Gavin Hamilton had conducted in the villa area in 1796. Two female heads in Parian marble from the same period are in the Glyptothek in Munich, while a ram's head in Pentelic marble, a Greek original dated between the 5th and 4th centuries BC, is now at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Berlin holds a statue of Artemis in white marble, a copy of a 4th-century original, and finally, a group of 8 sculptures (35 male torso; 59 Venus; 74 Discus Thrower; 50 statue of Plotina with Juno's attributes; 194 statuette of a boy; 407 herm of Alcaeus; 458 bust of Lucius Verus; 459 bust of Lucilla) is currently owned by the Torlonia family and kept in their museum within a family palace on Via della Lungara (not accessible).

A life-sized marble ram was kept at Villa Mattei, purchased by Corvisieri, and another bust of Lucius Verus (Glyptothek n. 253) is in Munich. Other sculptures were located in the former Corsetti house on Via Monserrato, originating from the noble Planca Incoronati family, who were the previous owners of the Acqua Traversa estate in the 17th century.

La villa di Lucio Vero fu devastata da scavi alla ricerca di opere d’arte, in particolare nel ‘600, e poi dalla costruzione della moderna Villa Manzoni nella prima metà del XX secolo. Oggi la lussuosa residenza, costruita scenograficamente a terrazze verso la valle dell’Acquatraversa, conserva parte dell’imponente muro di sostruzione con nicchie, in cui si riconoscono almeno due fasi costruttive; della struttura originale restano inoltre: un portico a pilastri, una cisterna a cunicoli, forse pertinente alla preesistente villa repubblicana, ed una serie di ambienti sulla terrazza superiore, decorati a mosaico e in opus sectile, quest’ultimo in forme particolarmente sontuose.

Fragments of colored vitreous paste plaques and marble inlays.

Lucius Verus's villa was devastated by art-hunting excavations, particularly in the 17th century, and later by the construction of the modern Villa Manzoni in the first half of the 20th century. Today, the luxurious residence, scenically built in terraces towards the Acquatraversa valley, preserves part of the imposing retaining wall with niches, showing at least two construction phases. Other surviving original elements include: a pillared portico, a tunnel cistern (perhaps belonging to the pre-existing Republican villa), and a series of rooms on the upper terrace decorated with mosaics and particularly sumptuous opus sectile.

Lucius Verus's villa is considered an important study site for another class of material it was rich in: glass tesserae decorations, used for both wall decoration and opus sectile flooring. It is the grand use of glass – employed not only for artifacts and domestic objects but, following a practice rarely attested in public buildings or luxurious private residences, as furniture veneer and architectural decoration – that constitutes the villa's significant scientific interest. The enormous quantity of polychrome glass tesserae preserved in the Gorga Collection (about 30,000 out of a total of about 150,000 glass artifacts), and those dispersed in other private and museum collections, skillfully mixed and composed to form panels with geometric or vegetal motifs and then masterfully applied to floors and walls, must have astonished and bewildered guests of the imperial residence, dazzling them with a whirlwind of images and colors. This retrospectively confirms the words of Iulius Capitolinus, biographer of Lucius Verus, about the character's dissoluteness and the splendor and luxury in which he lived.

In 1879, fragments of extremely rich inlaid floors made of colored vitreous enamels and bone were sold to a Roman antiquarian in large baskets.

- G. Tomassetti, La campagna romana antica, medioevale e moderna

The discovery during initial surveys in 1988 of fragments of colored glass paste plaques and marble inlays allowed the attribution to Lucius Verus's villa of a large quantity of figurative panels, evidently the result of past recoveries, now in foreign museums or private collections. For example, some of these plaques were used in the artificial reconstruction of a bone and glass triclinium bed conserved at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Couch and footstool with bone carvings and glass inlays (2nd century CE) from the imperial villa of Lucius Verus (co-emperor, A.D. 161–169), on the Via Cassia outside Rome. - The MET Museum.

These pieces of furniture have been reassembled from fragments, some of which may come from the imperial villa of Lucius Verus on the Via Cassia outside Rome. It is not certain that the square glass panels are original to the bed frame and stool, but the carved bone inlays are paralleled on other Roman couches. On the couch legs are friezes of huntsmen, horses, and hounds flanking Ganymede, the handsome Trojan youth who was abducted by Zeus in the guise of an eagle to serve as his wine steward; on the footstool are scenes of winged cupids and leopards; and on the sides of the bed frame, the striking lion protomes have eyes inlaid with glass.

The Historical Vicissitudes of the Villa

In the early 17th century, the Borghese family bought the various lands of Acqua Traversa. Three centuries later, the estate passed to the Ruffo della Scaletta princes, who held it briefly: between 1923 and 1924, they began excavations for the construction of an imposing villa right on the hilltop overlooking the Acquatraversa ditch valley. The land was then purchased by Count Gaetano Manzoni (1871-1937), an Italian diplomat of the Fascist period. He commissioned the eclectic architect Armando Brasini (1879-1965) – one of the most famous and prolific of the Fascist era – to build a scenographic residence richly adorned with marbles, stuccoes, and decorations worthy of a royal palace, surrounded by a vast park occupying the hilltop and slope down almost to the valley ditch.

Lucius Verus' villa, general floor plan.

The modern construction thus came to be situated directly on the still-visible ruins of the Antonine residence, cataloged during those years by Giuseppe Lugli, the first to compile a detailed list of everything still visible. He described the presence, in the western sector of the park, of structures datable from the 1st century BC to the Augustan age: walls in opus incertum, two types of cisterns (one with tunnels dug into the bedrock and lined with hydraulic cocciopesto, and a semi-subterranean one with a double chamber covered by a barrel vault). In the eastern sector, he documented an open-air reservoir. Along the hillside is a buttressing wall with a double system of niches, built in brick and attributed to the Antonine phase. Lugli also dated some geometric-design mosaics found during earthworks for the Villa Manzoni garden to the 2nd century AD (until the 2005-2009 excavations).

Architect Brasini, despite the numerous and complex Roman remains, built the modern structure directly on the ancient foundations and, while arranging the park and creating the massive retaining wall for the upper terrace, intersected both the mosaic-decorated rooms and the double-niche wall recorded by Lugli. The passionate appeals of the then Superintendent of Monuments, A. Muñoz, denouncing the excessive proximity of modern walls to ancient ones, were in vain.

Count Manzoni resided only briefly in the villa. After his death, it passed to his wife and, after World War II, became a restaurant and nightclub. In 1953, the widowed Mrs. Manzoni sold the residence and the entire park to the Istituto Nazionale Previdenza Dirigenti Aziendali (INPDAI). Unable to proceed with a clearly speculative building subdivision of the now-protected (both naturalistic and archaeological) park, INPDAI let the entire complex fall into ruin.

In subsequent years, numerous fires destroyed the park and Brasini's villa, ruining both the modern structures and the few ancient remains that had survived the interventions of the 1920s. The abandonment of Villa Manzoni and its surrounding park ended in 2004 when the entire complex was purchased by the Republic of Kazakhstan, the current owner, which chose Brasini's building as the seat of its Embassy to the Italian State.

Villa Manzoni in a state of abandonment during the 1980s.

The Villa's Curse

The esoteric world has made this sumptuous 1920s mansion the protagonist of near-paranormal events, widely fueled by popular beliefs. It was built on the ruins of Lucius Verus's villa, itself constructed on a site sacred to the Etruscans. Some believe a curse stems from the desecration of this place – a necropolis and also a site of ancient ceremonies and religious rites just kilometers from the ancient city of Veii. It's said to be reachable via tunnels dug into the natural tuff bedrock (with a slightly ogival vault and no hydraulic lining), under the hill during the earliest period between the 2nd and early 1st centuries BC, to drain what was then agricultural land.

Spirits three thousand years old are said to still wander the villa's corridors and its underground tunnels. Tales of satanic rites, unexplained screams, and terrifying apparitions have contributed to the villa's 'cursed' reputation.

Until a few years ago, Villa Manzoni lay abandoned since the 1950s. In 2003, an American multinational bought it, but reportedly strange phenomena prompted the company to dispose of it as quickly as possible. The following year, it became the restored seat of the Kazakh Embassy.

Today, the site, being within an Embassy, is closed to the public and accessible only by request.

Rome, via Cassia,477