The Clivus of Acilius and the Disappearance of the Velia: The Story of an Urban Transformation

Rome, Italy

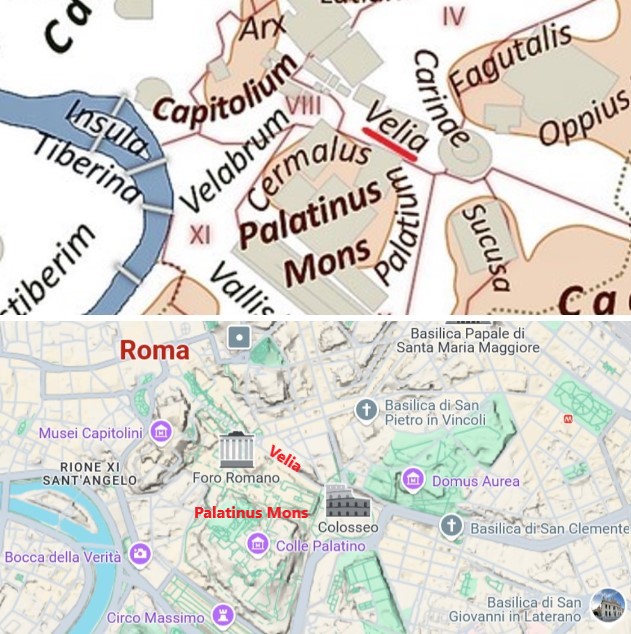

The urban transformation of Rome in the early 20th century also included the destruction of the Velia, a saddle-shaped hill about 40 meters high that stretched between the slopes of the Oppian Hill and the outskirts of the Palatine, separating the area of the Imperial Fora from the Colosseum.

Where the Velia once stood, today we find the Clivus of Acilius, a street located in the Monti district, between Via dei Fori Imperiali and Belvedere Antonio Cederna. It was built in 1937, following the construction of the retaining wall between Via dei Fori Imperiali and Villa Rivaldi, which created this incline. It was decided to name it the Clivus of Acilius in memory of the Compitum Acilii—a crossroads shrine built during the time of Augustus as part of the Emperor’s urban renewal program, located near the present-day clivus. The Acilii, from whom the compitum took its name, were an important family in Ancient Rome, existing until the 5th century AD. The same family owned the estate along Via Salaria Nova, where they commissioned the famous Catacombs of Priscilla.

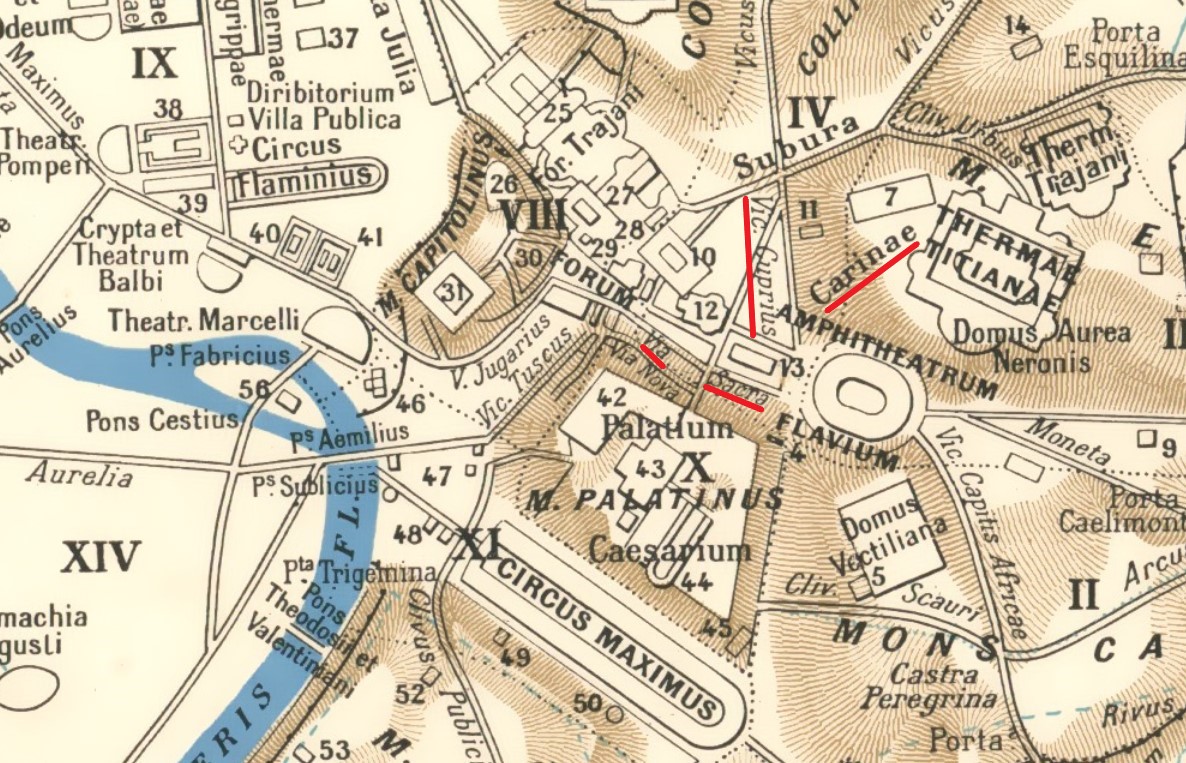

Location of the Velia.

Between 1931 and 1932, the Velia was demolished to make way for a new city thoroughfare, initially intended to be called Via dei Monti (in contrast to Via del Mare), but later named Via dell’Impero (today’s Via dei Fori Imperiali). This was meant to be a grand, monumental, and scenic road connecting the Vittoriano at Piazza Venezia (a symbol of the Italian Risorgimento) to the Colosseum (a symbol of the Eternal City). As part of Mussolini’s urban renewal of Rome, this idea sought to create a sense of continuity with the urban renewal of Ancient Rome under Augustus.

A unique stage in the world, marked by some of the capital’s most important monuments, the road was inaugurated on October 28, 1932, to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the March on Rome, becoming the ideal backdrop for parades in Fascist Rome and other regime rituals.

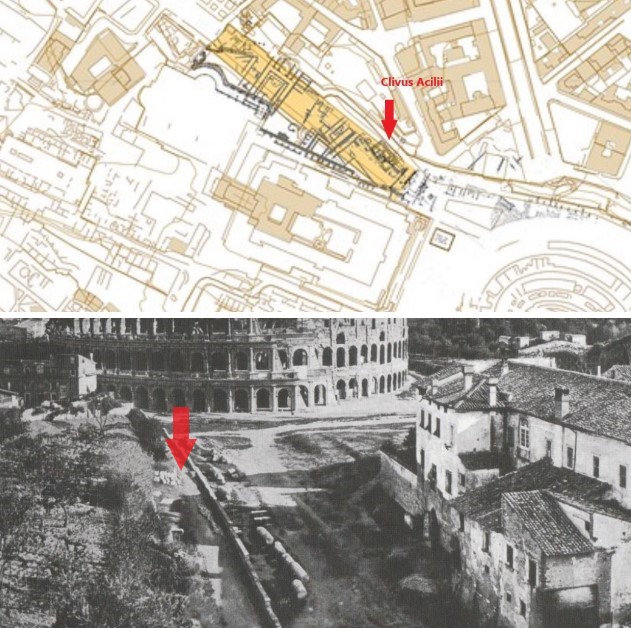

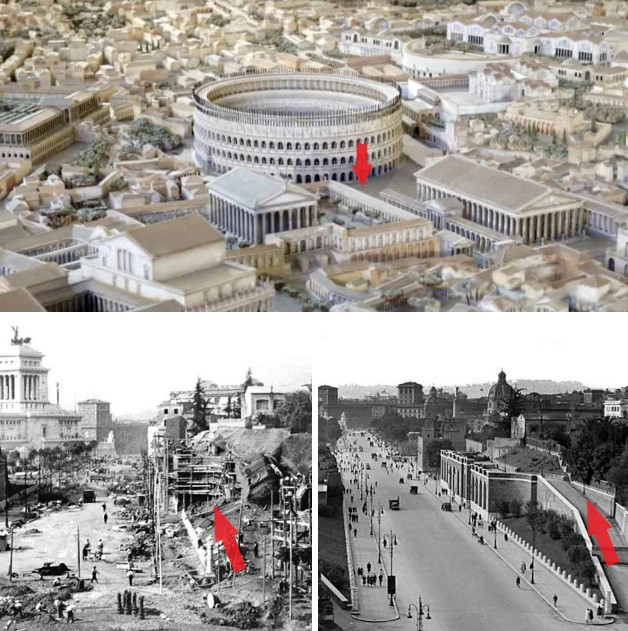

Top – The area of the Velia’s demolition (in yellow) and Roman-era structures (in black) uncovered between 1931–1932, mapped onto modern topography. Bottom – Buildings on the slopes of the Colosseum and the Velia before demolition. The red arrow indicates the Clivus of Acilius.

The archaeologist Antonio Maria Colini, who coordinated the excavations, was given extremely tight deadlines, which—as he repeatedly lamented—compromised the necessary care in the work and the completeness of documentation. With summary excavation reports, photographs, watercolors, sketches, notes, plans drawn during the excavation, and the study of highly fragmentary materials, only an approximate topographic reconstruction of the Velia area was possible, albeit with many uncertainties.

The price paid by the artistic and archaeological heritage due to this demolition was very high: completely destroyed structures from the modern, medieval, and Roman eras, including a wealthy domus belonging to the important Attii Insteii family, with frescoes and numerous statues now preserved in the Centrale Montemartini.

Display case with fragments related to the demolition of the Velia in the 1930s.

The Compitum Acilii

The compitum Acilii stood in the ancient Regio IV. In an urban context, the term compitum seems to indicate both the intersection of two or more streets (thus meaning a crossroads), the shrine that stood at the crossroads (meaning a compital shrine), and a neighborhood (in this sense, synonymous with vicus). Of course, not all intersections were compita, only those formed by the most important streets (Varro, De Lingua Latina, 6.25). Only at compita were sacred shrines erected—in this sense, the two meanings coincide. Conversely, minor streets could define blocks but not compita in the sense of neighborhoods, and no compital shrines existed at their intersections.

During the construction of Via dei Fori Imperiali, a small Augustan-era sanctuary of the Lares Compitales, the Compitum Acilii, was discovered and destroyed.

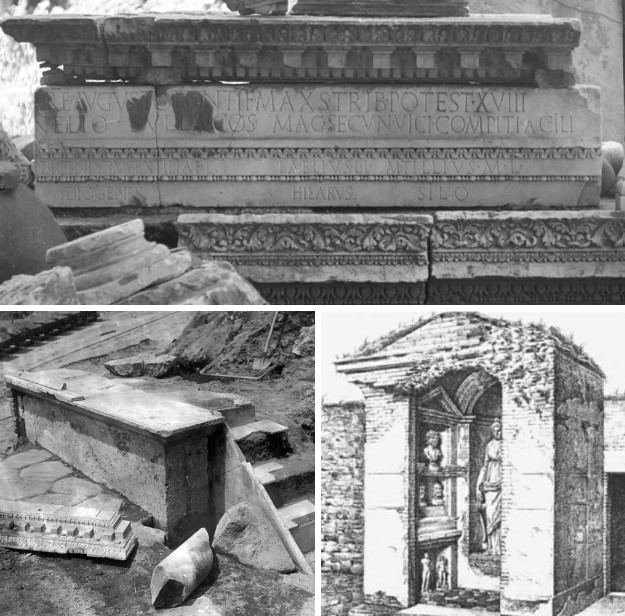

The shrine stood on a white marble-clad podium, 1.40 meters high, 2.38 meters wide, and 2.80 meters deep. Access to the podium was via four steps. The small cella was only 1.56 meters deep. From the shrine, a fragment of a column and remains of the entablature were found, consisting of a two-arched architrave whose slightly protruding upper band was supported by a decorated beam. An inscription was present:

[Imp(eratore) Cae]sare Augusti(!) pontif(ice) max{s}(imo) trib(unicia) potest(ate) XVIII [imp(eratore) XIV L(ucio) Cor]nelio Sulla co(n)s(ulibu)s mag(istri) secun(di) vici compiti Acili Licinius M(arciae) Sextiliae l(ibertus) Diogenes / L(ucius) Aelius L(uci) l(ibertus) Hilarus / M(arcus) Tillius M(arci) l(ibertus) Silo

While Emperor Caesar Augustus, Pontifex Maximus, in the 18th year of his tribunician power and 14th imperial acclamation, with Lucius Cornelius Sulla as consul, the second magistrates of the vicus Compiti Acili consecrated (this shrine): Licinius Diogenes, freedman of Marcia Sextilia; Lucius Aelius Hilarus, freedman of Lucius; and Marcus Tillius Silo, freedman of Marcus.

The joint consulship of Augustus and Lucius Cornelius Sulla fell in 5 BC, the year in which the second group of magistrates of the vicus Compiti Acili established the shrine. Augustus, in 7 BC, had divided Rome into 14 regions, distributing the 265 vici among them.

Augustus’s reform of the regions and streets also revised the reorganization of the compita (Compitalia), which now had to include the cult of the Genius Augusti. Suetonius (Aug. 31) testifies that the Princeps "instituted the decoration of the Compital Lares twice a year, with spring and summer flowers."

In the Augustan reform, images of the Genius Augusti were included in the small shrines alongside the Lares. Augustus was particularly close to his freedmen, and they to him. Thus, portraits of the Princeps were made and displayed in the vici. In this way, Augustus became part of the state cult and an integral part of the locality.

On the tenth anniversary of the regional reform, the magistrates of the vicus Compiti Acili also founded an altar, the ruins of which were found in the 1932 excavations. This marble altar, decorated with a laurel wreath on its sides, bore an inscription:

(Bucio) [o] riois (Turi) (ibertus) Bucci [o]

It was thus founded by the magistrates in the 10th year after the reform (i.e., 3–4 AD), commemorating the event and the reorganization of the vici.

Only a few remains of the shrine and its associated altar have survived.

The shrine, facing northeast, certainly marked the intersection between the road leading from the Sacra Via toward the Esquiline (today’s Via della Polveriera) and other streets that must have served as boundaries between different neighborhoods (if not different urban regions)

Remains of the compitum Acilli discovered in 1932 during the Velia’s demolition, including the inscription on the architrave, and an example of a compitum from Ostia Antica.

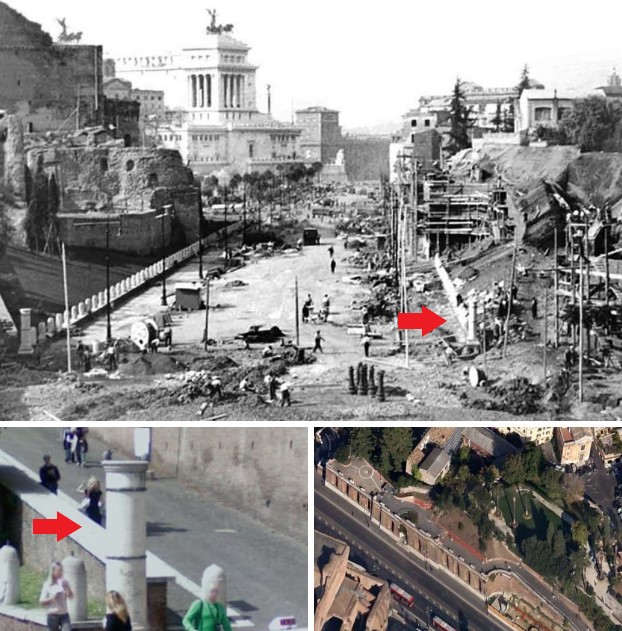

A small column at the entrance of the modern Clivus of Acilius onto Via dei Fori Imperiali marks the spot where the shrine was discovered, though it originally stood on a street level almost seven meters above the current road. Thus, we do not know its exact original position, but we do know that on the western edge of Via della Polveriera, the Magistri secundi vici compiti Acili built the compital shrine in the first half of 5 BC, and their successors nine years later (Mag(istri) vici comp(iti) Acili anni X) dedicated the altar.

The establishment of the vicus likely dates to 7 BC; in its first year, the neighborhood probably lacked a sacred shrine. The altar (or a new altar) was dedicated in 3–4 AD. The independent or delayed dedication of the altar may relate to the deaths of Lucius and Gaius Caesar (in 2 and 4 AD, respectively) and the extensive measures of heroization directed at the young princes. In this sense, the hypothesis identifying the Lares Augusti with the deceased members of the imperial household may find confirmation. The Lares Augusti, together with the Genius of the Princeps, protected the urban space.

Clivus of Acilius and the small column marking the approximate location of the compitum Acilii.

The Neronian Fire and Its Aftermath

The Great Fire of Nero was an epochal event for the urban history of this part of Rome. Tacitus (Annals, 15.41–43) recounts how Regio IV was one of three urban regions completely devastated by the fire, along with Regio X and XI. This is confirmed by the thick layer of rubble found beneath later buildings. The event thus marks a decisive turning point in the urban and monumental history of the neighborhood: in fact, buildings destroyed in the fire or newly constructed afterward could no longer be identified with those known from ancient sources for the periods before and after 64 AD.

Thus, the buildings around the Compitum Acilium were later buried under a powerful layer of debris, above which a new urban plan emerged, heavily influenced by the insertion of the Domus Aurea between the Palatine and the Oppian Hill. However, it remains objectively difficult to distinguish Nero’s constructions from Flavian or later modifications in the post-fire planning. What is certain is that after the fire of 64 AD, the compital shrine disappeared.

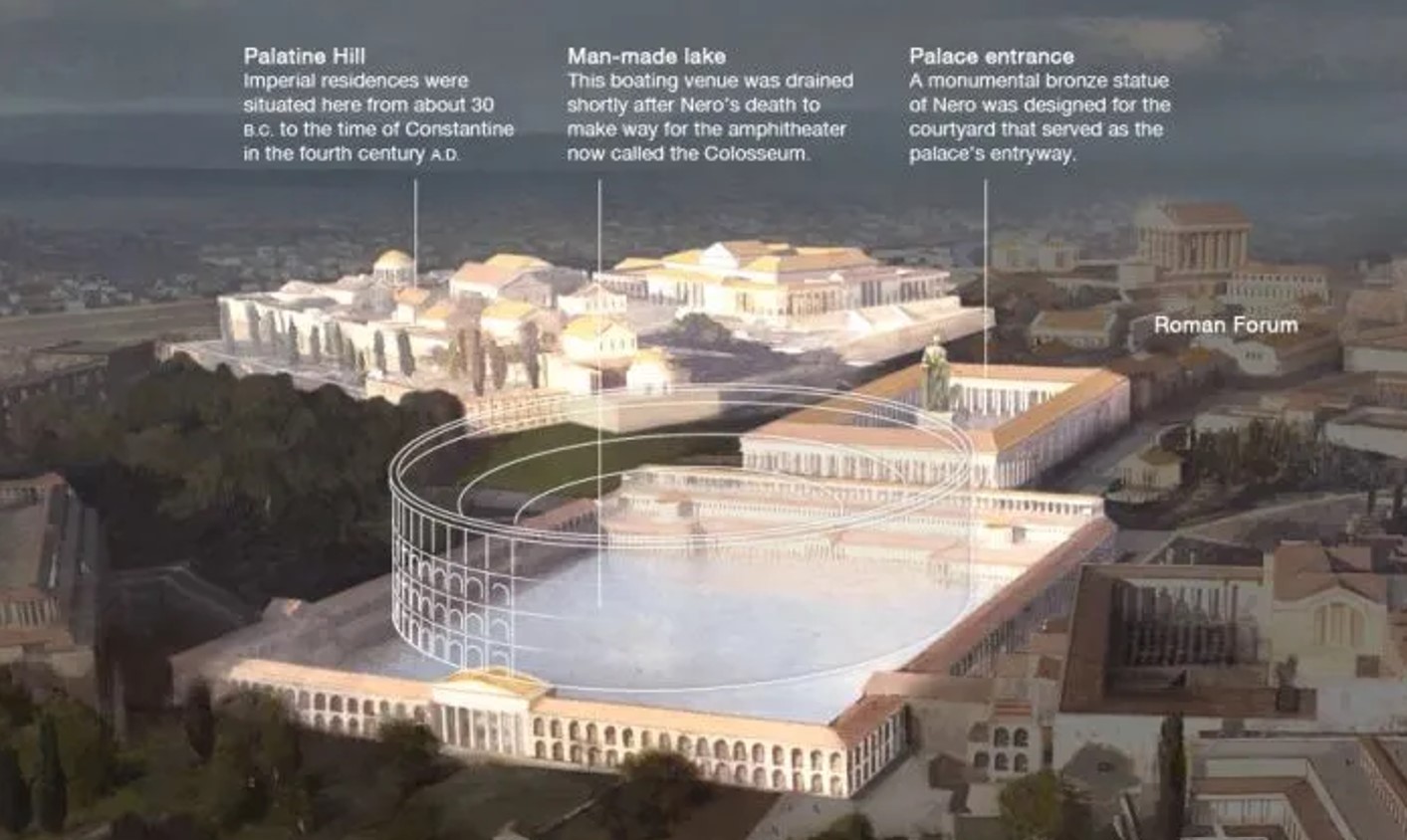

Domus Aurea and an overlay of the colosseum on Neros lake.

The Tigillum Sororium and Topographic Reconstruction

A fragment of the fasti Fratrum Arvalium allows us to establish a very close topographic relationship between the Compitum Acilium and another famous monument in the area: the Tigillum Sororium.

Fidei

in Capitolio. Tigillo Soror(io)

ad Compitum Acili(um)

The Tigillum, by its very nature, could not have been located directly at the crossroads of the Compitum Acilium but necessarily straddled one of the roads intersecting there. Dionysius of Halicarnassus indicates the road on which the Tigillum stood when narrating the conclusion of the trial of Horatius, guilty of killing his sister, who had been betrothed to one of the slain Curiatii. In the trial, King Tullus Hostilius, while accepting the people’s decision to acquit the young man,

... thought that the judgment of men was not enough for those who wished to maintain respect for the gods. Summoning the pontiffs, he ordered them to appease the gods and other deities and to purify Horatius with the expiatory sacrifices customarily used for involuntary homicides. They erected two altars, one to Juno, protector of sisters, and the other to a native god or deity called Janus in the local language, with the epithet of the slain Curiatii. After performing ceremonies for them, they carried out other expiatory sacrifices and finally led Horatius under the yoke. It is a Roman custom, when taking power over surrendering enemies, to plant two vertical posts and place a third crosswise, then make the prisoners pass beneath it and, once they have done so, send them home free. This they call the 'yoke.' Those who purified the young man used it at the end of the customary expiatory rites. The place in the city where they performed the rite is considered sacred by all Romans. It is in the alley that descends from the Carinae for those going toward the Vicus Cuprius. There, the two altars built at that time still stand, and above them stretches the beam fixed to the opposing walls, above the heads of those exiting the alley, called in the Roman language the 'Sister’s Beam.' This place is preserved by the Romans as a memorial to that man’s misfortune and is honored with annual sacrifices...

Augustan Regions.

From a topographic reconstruction perspective, Dionysius’ account allows us to establish that::

• The Tigillum stood on a road descending from the Carinae (and likely passing through them, in whole or in part).

• The road descending from the Carinae led into the Vicus Cuprius.

• Regardless of which alley (the one descending from the Carinae or the Vicus Cuprius) one exited by passing under the Tigillum, the latter must have been located not far from the point where the two met.

• The Carinae were higher than the Vicus Cuprius.

• The Vicus Cuprius was likely not within the Carinae.

Thus, considering the position of the Tigillum Sororium near the Compitum Acilium, the road descending from the Carinae should be identified with one of those descending toward the compitum (excluding the ancient axis traced by Via del Colosseo, which instead descends from the compitum area toward the Suburra). Consequently, the Vicus Cuprius must be identified with a road lower than the first, leading toward the compitum-Tigillum area.

The Sacra Via and Nero’s Urban Plan

The Via Sacra was widened and, along with the surrounding roads, realigned according to the axis of Nero’s palace complex (Sacra Via, vestibule, atrium, porticoes, and the lake in the valley of the Amphitheater). The southern slope of the eastern Velia was cut away to make room for the atrium and vestibule of the palace (which, certainly located on the site of Hadrian’s later Temple of Venus and Roma, erased the original stretch of road between the Summa Sacra Via and the Compitum Acilium area). Further structural overlaps affected the area once occupied by the Compitum Acilium at an unspecified time in the mid-Imperial period.

Location of the Clivus of Acilius in the model of Ancient Rome.. 1932 photos of the Velia’s demolition, showing the destruction and later reconstruction (1945 photo) of the Clivus of Acilius.

Rome’s Metro Line C: A Journey Through Time

Rome’s Metro Line C does not just travel through urban space but also through time. It represents a unique opportunity to enhance our understanding of Ancient Rome, as archaeological excavations have allowed the discovery of ancient structures or parts of them in excellent states of preservation. These findings have become protagonists in a true valorization of the past in the present era, through an underground museum, as in the case of the Colosseo-Fori Imperiali station. Artifacts are displayed inside glass columns in a museum space unique in the world. Indeed, the station will welcome visitors by showcasing discoveries made during its construction.

For the metro’s construction, part of the Muñoz Wall had to be temporarily removed, re-exposing stratigraphies and structures spared by the Velia’s demolition and preserved behind the containment wall. These pertain to residential buildings that occupied the southeastern slope of the hill in the Imperial era.

Originally, the summit of the Velia stood at 43 meters above sea level, while Via dei Fori Imperiali lies at about 22 meters. From around 32 meters above sea level, the remains of a complex of structures from different building phases emerged, spanning from the early Imperial period to late antiquity. These were arranged on terraces sloping east/southeast, likely accessible from the ancient road corresponding to today’s Via del Colosseo.

Imperial Fora Station, archaic wells.

The archaeological investigations for the metro’s construction led to unexpected discoveries of particular importance for interpreting the history of the area. Among the few surviving archaeological traces spared by demolition, the remnants of archaic wells for groundwater extraction stand out. These descend deep into Pleistocene silt-sand deposits. The fill layers of the wells yielded materials covering a broad chronological span, from the 7th to the 2nd/1st century BC. Of great interest are intact material contexts found in the wells’ fill, likely linked to ritual activities associated with the sacredness of water and offerings made upon their closure.

Of the 25 wells investigated, 9 were unlined and had footholds carved into the compact silt-sand sediments of the Velia, while 16 were lined with shaped tuff slabs, which were dismantled and preserved. These will play a central role in the station’s archaeological display.

Underground museum at the 'Colosseo-Fori Imperiali' station.

The excavations have allowed a more precise delineation of the extent of the Velia hill (destroyed in 1932) and the scale of the archaeological remains spared by demolition and preserved behind the Muñoz Wall along Via dei Fori Imperiali and Piazzale del Colosseo. Structures and a large quantity of well-preserved materials were uncovered.

The decision to place most of the station’s structure in the area of the demolished Velia significantly limits interference with archaeological stratigraphy in this crucial zone of Ancient Rome. Some of the artifacts will be visible by the end of September 2025 in the museum display inside the Colosseo-Fori Imperiali station.

Rome, Via dei Fori Imperiali, 43