Aqua Paola: How Popes, Frauds, and Cannon Fire Forged Rome’s Iconic Fountain

Rome, Italy

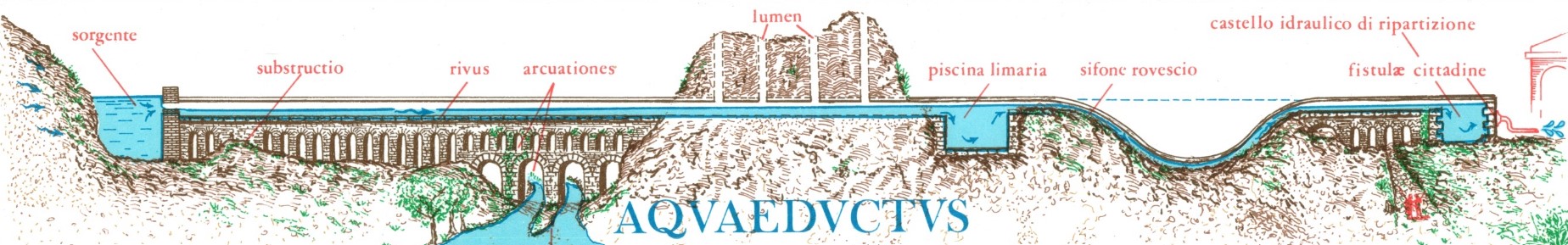

Since ancient times, Rome has benefited from numerous springs scattered among its seven hills. Between the 7th and 6th centuries BCE, the Etruscan kings (Tarquinius Priscus, Servius Tullius, Tarquin the Proud) began constructing hydraulic structures and infrastructure. While water drainage techniques originated with the Etruscans, the Romans pioneered aqueduct engineering. These systems channeled water into the city through underground pipes, supplying public fountains, baths, and troughs, as only the wealthy had private plumbing.

Under Emperor Augustus, water management was entrusted to the Curatores Aquarum. One such curator, Sextus Julius Frontinus (ca. 40–104 CE), under Emperor Nerva in 97 CE, documented Rome’s nine aqueducts and three main pipelines (fistulae) dividing water into:

• Imperial water for the imperial family and grand baths;

• Public water for communal use;

• Private water (40%), reserved for privileged families.

In his treatise De aquaeductu urbis Romae, Frontinus lamented that despite strict laws, senatorial decrees, and precautions, fraud and corruption persisted, with people illegally diverting water by bribing officials. He famously wrote:In his treatise De aquaeductu urbis Romae, Frontinus lamented that despite strict laws, senatorial decrees, and precautions, fraud and corruption persisted, with people illegally diverting water by bribing officials. He famously wrote::

Magna cura multiplici opponenda fraudi est.

Great care must be taken to counter manifold fraud.

Rome’s aqueducts fueled a thriving water culture: fountains, baths, naumachiae (naval battle spectacles), and water parks. By 410 CE, the 11 aqueducts supplied 1,212 public fountains, 11 imperial baths, and 926 public baths. The aqueducts supplied the city with a maximum flow of drinking water reaching 13.5 m3/s. The total length of this aqueduct system amounted to 504.7 km. The last aqueduct was built by Emperor Alexander Severus in 226 AD.

Most of the aqueducts constructed by the Romans originated from the left bank of the Tiber River. Only one, Trajan’s Aqueduct, built in 109 AD, began on the right bank, with a total route estimated at approximately 57 km.

In Imperial Rome, supplying drinking water to its vast population was indeed a problem of substantial importance. It was for this reason that the emperor commissioned the aqueduct: to provide water to the Regio XIV 'Transtiberim' ('beyond the Tiber') on the river’s right bank. However, this area was among the last to be supplied, as it was then considered a peripheral zone.

Operation of a Roman aqueduct

The siege of Rome in 537 CE by Vitiges, King of the barbarian Goths, marked the decline of the Roman water supply system. The Goths destroyed the aqueducts to cut off the city’s water resources.

The aqueducts were never rebuilt or restored, and most of their arches collapsed. By the end of the Middle Ages, only one, the Aqua Virgo, remained in use, forcing Romans to draw water from wells and the Tiber.

Beginning in the 16th century, popes restored some ancient aqueducts and built new ones, bringing water back to both the upper and lower parts of the city.

These pontiffs aimed to provide the city with excellent drinking water. They took care to publicize this goal, enshrining it in their Constitutions on the Waters and even in the inscription on the grand façade of the Acqua Paola on the Gianicolo Hill: saluberrimis and fontibus collectam (“collected from the healthiest springs”).

Furthermore, in these Constitutions, the popes established regulations for maintaining public and private fountains and managing water sales. They outlined measures to prevent clandestine water theft, ensuring it remained a communal benefit. Yet, as in antiquity, many secretly diverted double the allotted water, harming others (who had less available) and the administration (which struggled to collect taxes properly).

Three centuries later, in 1824, due to seasonal droughts and financial losses from illegal water tapping, Monsignor Bottiglia, President of the Waters, urged Pope Leo XII (Annibale Francesco Clemente Melchiorre Girolamo Nicola della Genga, 1760–1829) to conduct a comprehensive inspection of the water network to identify illegal connections and restore order. However, as soon as enforcement began, prominent figures—including princes, lawyers, and architects—resisted. In court, they questioned the water’s quality to justify avoiding taxes or claimed innocence, arguing that the fraudulent system had been inherited and had existed for “hundreds of years” or “time immemorial,” absolving them of responsibility.

Portrait of Pope Paul V (1605 ca.) by Caravaggio (1571–1610)

Among the restorer popes was Paul V (Camillo Borghese, 1552–1621). During his papacy, in 1608, he restored the Aqua Paola Aqueduct by purchasing springs originally part of Trajan’s Aqueduct from Duke Virginio Orsini. This project allowed water to reach homes in the Trastevere district and Gianicolo Hill for the first time, areas that had previously relied on wells and river water. However, the water was not perfectly drinkable, leading Romans to coin the phrase Valere quanto l’acqua Paola

(Worth as much as Aqua Paola water), meaning something of little or no value.

The restored aqueduct was Trajan’s original structure, revitalized during the Renaissance. Water was drawn from Lake Bracciano and, in antiquity, had powered Rome’s mills. A branch of the aqueduct was diverted to supply water to the Vatican, garden fountains, and those in St. Peter’s Square.

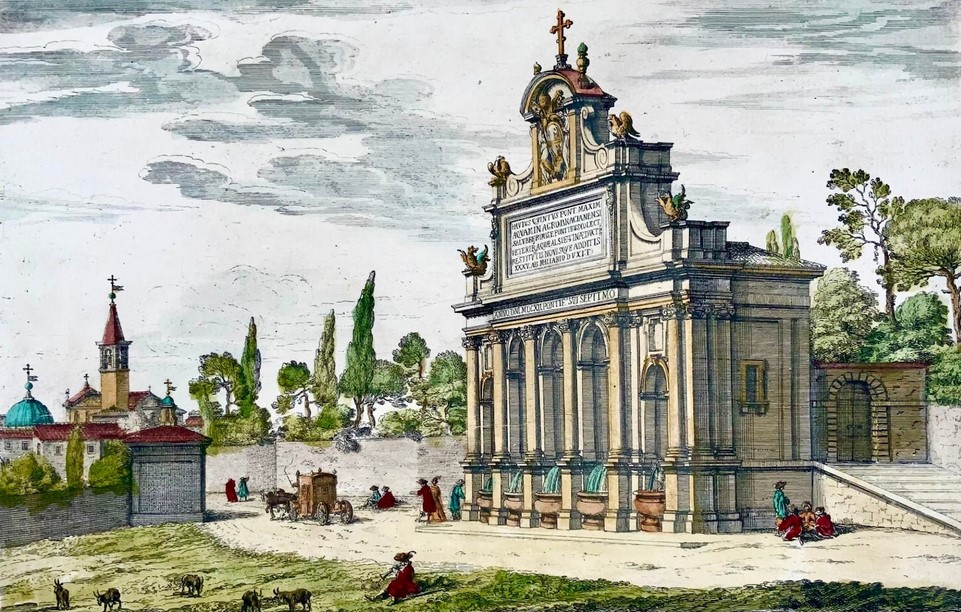

Fountain of the Acqua Paola in 1676 (G.B. Falda)

At the summit of the hill, Paul V commissioned a monumental fountain, the Fontana dell'Acqua Paola (also known as the "Paola Fountain" or "Fontanone", Big Fountain), as the terminal display of the restored Trajan Aqueduct. Though the Roman administration contributed to the aqueduct’s restoration, the pope’s primary aim was to secure a reliable water supply for his residence’s gardens, not to create a public fountain. By reviving the ancient aqueduct, Paul V fulfilled a goal shared by his predecessors.

Built swiftly between 1610 and 1612 by architect-engineer Giovanni Fontana, alongside Carlo Maderno and Flaminio Ponzio, the project cost just under 10,000 scudi (a papal currency). Inspired by the Fontana del Mosè (Moses Fountain) designed by his younger brother Domenico Fontana, the brothers also collaborated on the Lateran Palace, the Blessings Loggia, renovations to the Quirinal Palace (now the Italian President’s residence), and the raising of the obelisk in St. Peter’s Square.

To source materials, Pope Paul V ordered the dismantling of the Temple of Minerva in Nerva’s Forum and the reuse of marble from the Roman Forum. The fountain’s grand facade, adorned with columns, sculptures of dragons, angels, and monsters, and commemorative inscriptions, channels water in foaming torrents.

Modeled after a triumphal arch, the structure features five arches and six Ionic columns of red and gray granite—four of which were salvaged from the facade of Old St. Peter’s Basilica.

Above these rises a massive attic bearing an erroneous dedication to the Alsietina Aqueduct (from Lake Martignano, Lacus Alsiatinus, near Lake Bracciano) instead of Trajan’s Aqueduct. The attic is crowned by an arched niche with a cross and the Borghese heraldic symbols: a dragon and an eagle, held aloft by two angels (sculpted by Ippolito Buzio in 1610). Replicas of the dragon flank the attic’s ends. At the center lies a grand marble plaque, framed and inscribed in elegant lettering:

PAVLVS QVINTVS PONTIFEX MAXIMVS

AQVAM IN AGRO BRACCIANENSI

SALVBERRIMIS ET FONTIBVS COLLECTAM

VETERIBVS AQVAE ALSIETINAE DVCTIBVS RESTITVTIS

NOVISQVE ADDITIS

XXXV AB MILLIARIO DVXIT

Pope Paul V brought to Rome water collected from the healthful springs of Bracciano, restoring the old Alsietina ducts and adding new ones, drawn from the 35th mile.

Originally, the fountain lacked its current basin and plaza. Instead, five small basins caught the water spouts, and it stood at the edge of the steep Gianicolo Hill.

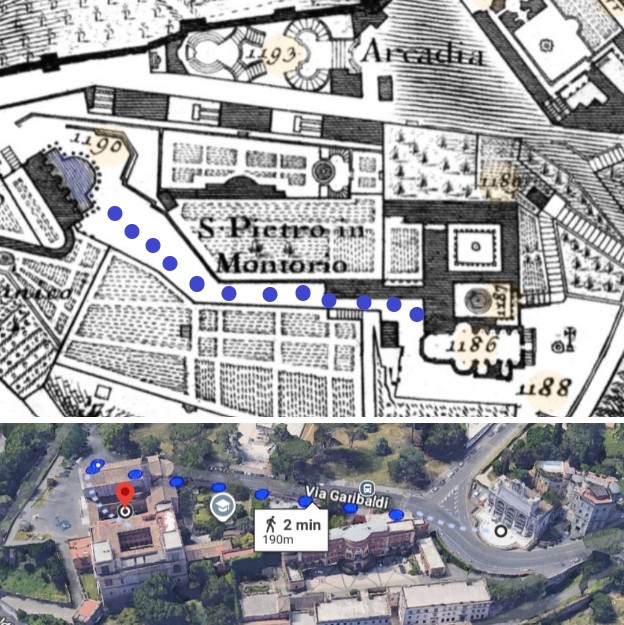

A notable anecdote: During a water test in 1610, the force of the gushing water shattered the marble balustrade and flooded the neighborhood as far as San Cosimato. The fountain’s turbulent debut underscored both its engineering marvel and the challenges of taming Rome’s waters. A contemporary account records:

1610 novembre 3. Sabato sera si diede esito d'una parte de l'acqua Paolina sopra d'una strada, che è a man dritta di San Pietro Montorio e uscì con tanto impeto, che fracassò la platea di marmo fattavi fare sotto la caduta e calando a basso verso San Cosimato ruppe alquante canne di un muro di un orto e allagò quasi tutti quei contorni, essendo stata aperta sino a lunedì sera, onde non si fa dubbio, che sarà abile a macinar molini a tutto transito.

November 3, 1610. On Saturday evening, part of the Acqua Paola was released onto a street to the right of San Pietro Montorio. It burst forth with such violence that it broke the marble slab placed beneath the cascade, tore through orchard walls, and inundated the surrounding area until Monday night. There is no doubt this water could power mills at full capacity.

Fountain of the Acqua Paola and San Pietro Montorio

Even then, as in ancient times, there were crafty citizens who flouted the laws. This is recalled in an edict issued by Pope Paul V—nicknamed Fontifex (the 'Fountain Pope') by Roman citizens—dated September 23, 1616. The decree forbade owners of villas and vineyards along the Acqua Paola conduit from plowing over underground pipes, planting near them (to avoid damaging the infrastructure), or illegally siphoning off water.

Fontanone

An inscription topped by the papal coat of arms, placed beneath the arch of the central niche, commemorates how in 1690 Pope Alexander VIII (Ottoboni, 1610–1691) oversaw the cleaning of the conduits, introduced new water sources, and commissioned the current piazza, reinforced with sturdy masonry. He also added the expansive and magnificent white marble basin, crafted by Carlo Fontana.

In 1698, Innocent XII enclosed the Aqua Paola Fountain with the present-day balustrade of small columns linked by iron bars, to prevent cart drivers from watering their horses there.

The structure, comprising three large central niches flanked by two smaller lateral ones, was built using travertine blocks quarried from the ruins of the Forum of Nerva.

Fontanone portrait by Caspar van Wittel at the end of the 17th century

During his journey in Italy in 1787, Goethe passed by the fountain and left a passionate description of the site, depicting it as a cascade of Acqua Paola water, tumbling from the five arches set within a triumphal arch.

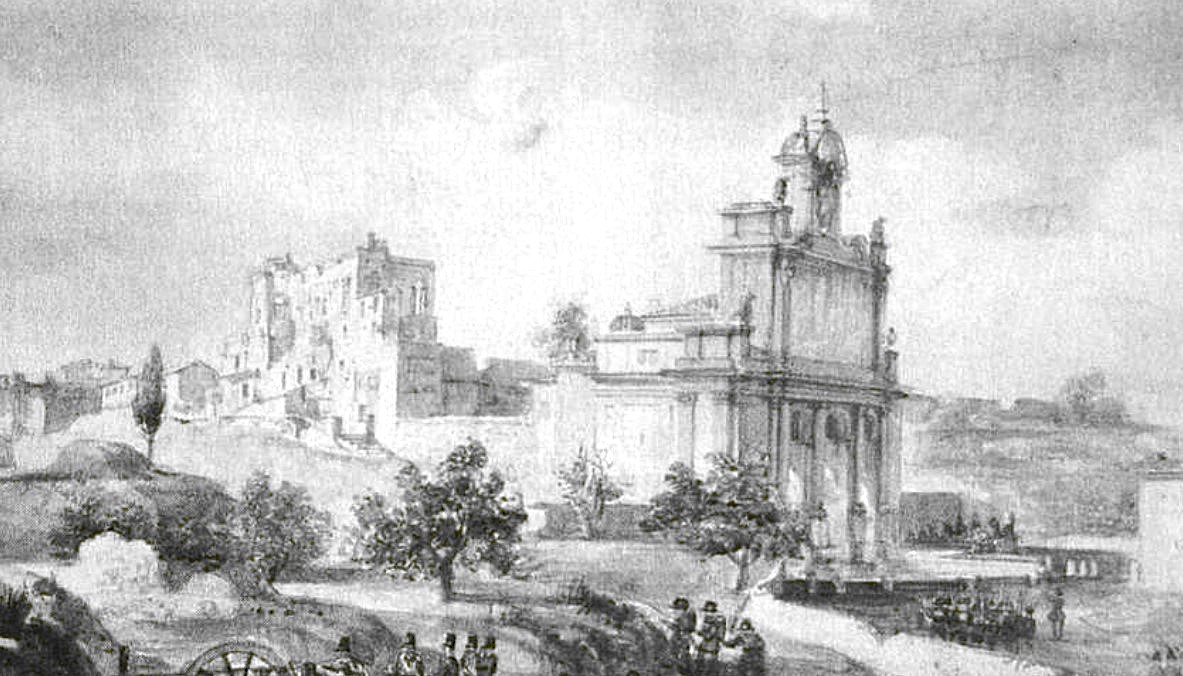

The fountain, at the heart of the fierce battles during the defense of Rome in 1849, was damaged by French cannons and underwent its first restoration in 1859, followed by others in 1934 and the 1950s. From 1901 to the 1930s, the water from the "Fontanone" powered Rome’s first hydroelectric plant.

Painting of the fountain , theater of the clashes for the Roman Republic of 1849.

Few know that a small gate on the right side of the Fontanone leads to the upper floors of the structure and to a rear fountain, likely built by Pope Paul V after the monumental fountain. Its purpose remains unknown.

Garden of Simples

Behind the monumental fountain lies the small "Garden of Simples" (Giardino dei Semplici), a remnant of a far larger 17th-century garden established by Pope Alexander VII Chigi (1655–1667) as a botanical garden. In 1820, under Pope Pius VII, this botanical collection was relocated to the gardens of Palazzo Salviati at the foot of the Gianicolo Hill. The smaller garden behind the fountain is accessible via a staircase at Via Garibaldi, number 30.

The term Semplici refers to medicinal plants, also called officinali (from officina, meaning "pharmaceutical workshop"). In the Garden of Simples, medicinal species are organized in raised beds. Some plants are cultivated directly in the surrounding soil, while others thrive in the Tropical Greenhouse.

(Note: "Semplici" (simples) derives from the medieval concept of "simples" or herbal remedies made from a single plant.)

Rome, via Garibaldi