The Barrel of Termini: Uncovering the Cistern That Sustained Ancient Rome’s Grandest Baths

Rome, Italy

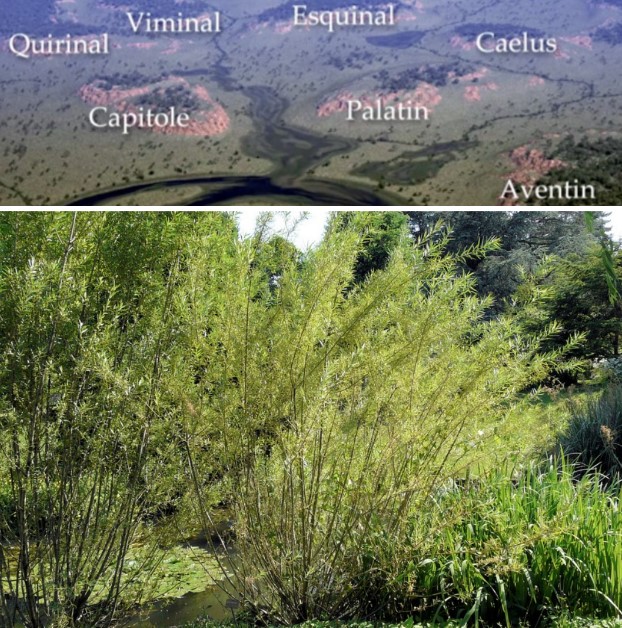

The Viminal Hill is the smallest of Rome's seven hills and likely the first to be included among the legendary seven hills upon which the city was founded. Its name derives from the willow trees (vimini) that once covered its slopes.

In just eight years (298–306 CE), the Baths of Diocletian were erected at the end of the road that ran through the valley between the Viminal and Quirinal Hills (the Vicus Longus, today’s Via Nazionale).

Seven Hills and the Salix viminalis Plant

To build this monumental complex, an entire urban district was demolished. The baths served the northeastern sector of the city, including the densely populated neighborhoods of the Quirinal, Viminal, and Esquiline Hills. Located within the old Servian Wall circuit and close to the Aurelian Walls—particularly near the Porta Nomentana and the Castra Praetoria (the Praetorian Guard barracks)—the baths stood as a testament to imperial grandeur.

Vicus Longus

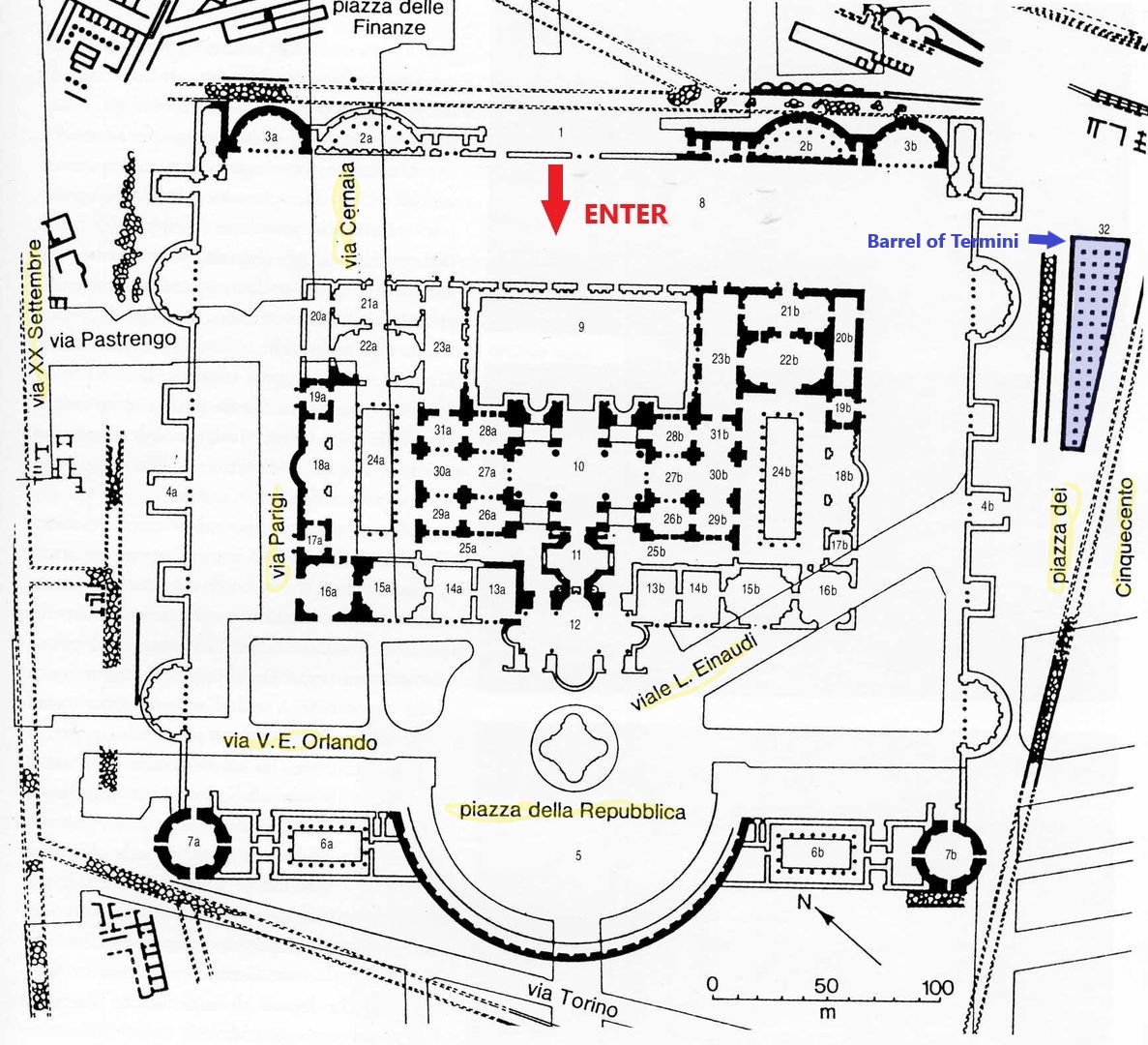

Today, the area once occupied by the baths spans Piazza dei Cinquecento (facing Termini Station), Piazza della Repubblica, Via Cernaia, and Via Volturno, where the main entrance originally stood. On the opposite side of the rectangular enclosure, a massive exedra was reconstructed in the late 19th century as the semicircular colonnade of Piazza della Repubblica.

Thermae Diocletianae. The elaborate complex of Diocletian’s Baths consisted of two main structures: the first was the enclosed building, centered around spaces dedicated to bathing and body care; the second was the trapezoidal cistern, positioned adjacent to the northeastern side of the walled enclosure.

The Thermae Diocletianae ranked among the largest in the Roman world, covering 13.5 hectares and accommodating up to 3,000 people at once. They featured a 4,000-square-meter open-air pool (natatio).

Natatio of Thermae Diocletianae

Commissioned by Emperor Maximian Augustus upon his return from Africa, the complex was dedicated to his co-emperor Diocletian. Diocletian, recognizing the vastness of the empire, had appointed Maximian as his equal in authority (Augustus) to address administrative challenges. While Diocletian ruled from Nicomedia (East), Maximian based himself in Mediolanum (Milan).

Emperors Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maximianus Herculius (Maximian, 250–310 CE) and Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus (Diocletian, 244–313 CE)

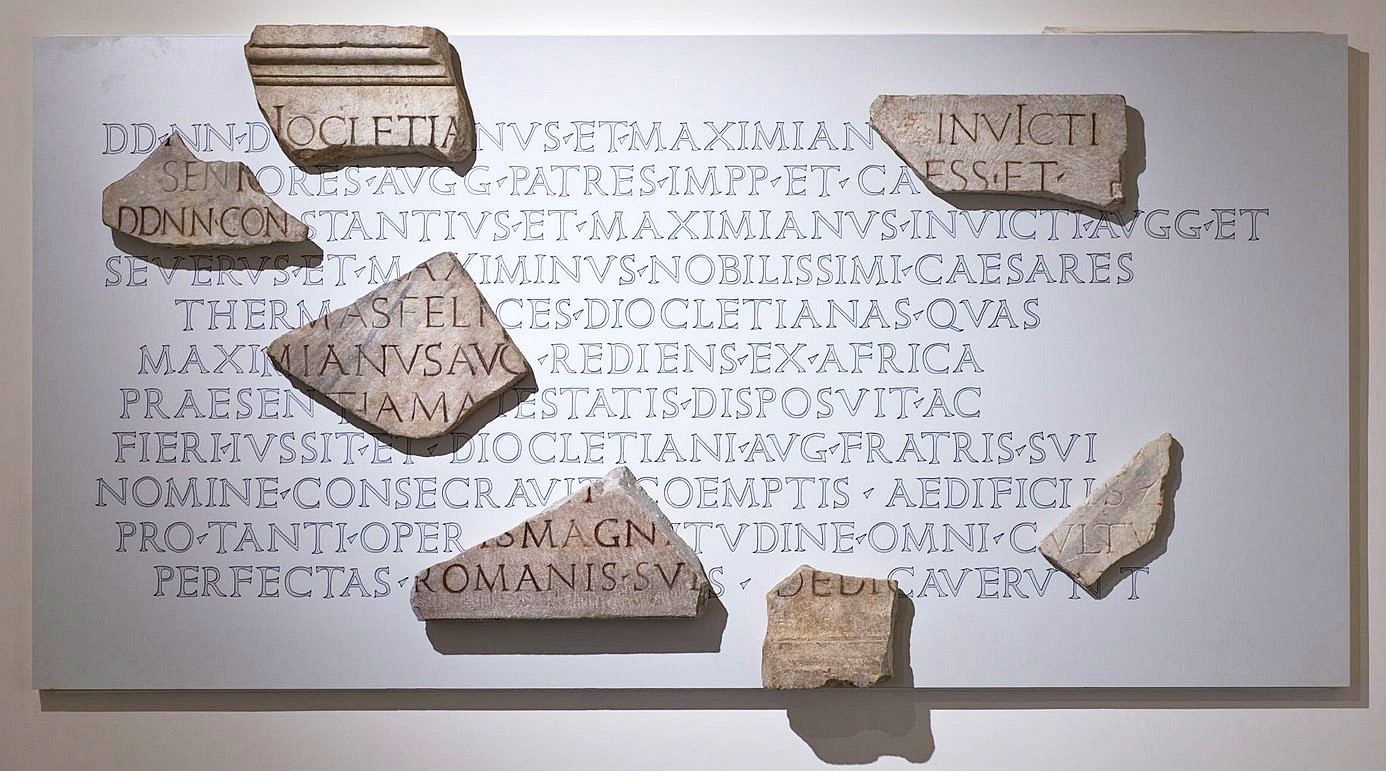

The dedicatory inscription (CIL VI, 1130 = 31242), originally displayed at the entrance, marked the final grand act of imperial propaganda. It proclaimed the baths as a gift from the emperors to the Roman people:

Our Lords Diocletian and Maximian, the unconquered Senior Augusti, fathers of the emperors and Caesars; and our Lords Constantius and Maximian, the unconquered Augusti; and Severus and Maximinus, the most noble Caesars—dedicated these auspicious Baths of Diocletian to their Romans. Maximian Augustus, upon his return from Africa, in the presence of His Majesty, decreed and ordered their construction, consecrating them in the name of his brother Diocletian. Buildings sufficient for such a grand project were acquired, and every detail was completed with splendor.

Dedicatory Inscription of the Baths of Diocletian

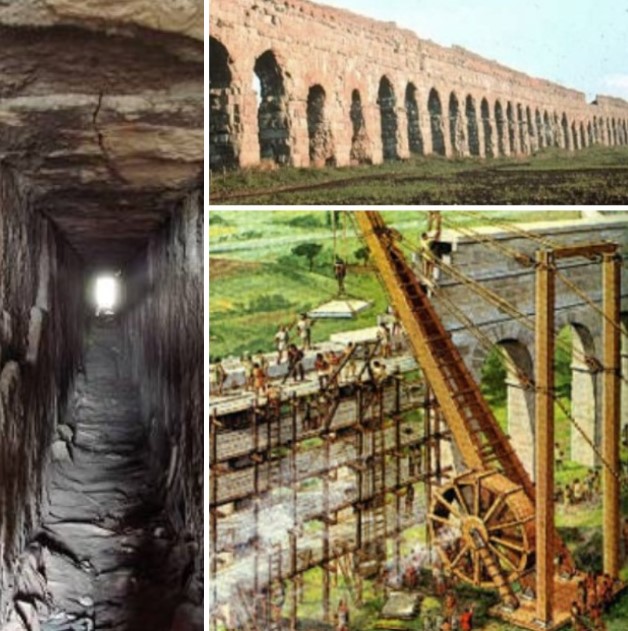

The baths were supplied by a branch of the Aqua Marcia aqueduct, built by praetor Quintus Marcius Rex in 144 BCE and restored multiple times before Diocletian’s reign, including by Agrippa in 33 BCE. The aqueduct drew water from springs in the upper Aniene River valley near the 26th milestone of the Via Valeria, likely including the Rosoline and Seconda Serena springs near modern-day Marano Equo. To meet the baths’ demands, a supplementary channel was constructed.

The Simbruini Mountains’ slopes host countless springs fed by the region’s vast karst aquifer. The rest of the aquifer permeates the Aniene’s alluvial plain. These springs collectively discharge over 8,000 liters per second—a volume well-known since antiquity and still harnessed by the Aqua Marcia to supply Rome. A sophisticated system of intakes, settling tanks, pumping stations, conduits, and reservoirs managed this resource.

Aqua Marcia Aqueduct in Rome and a stretch of its unbroken tunnel

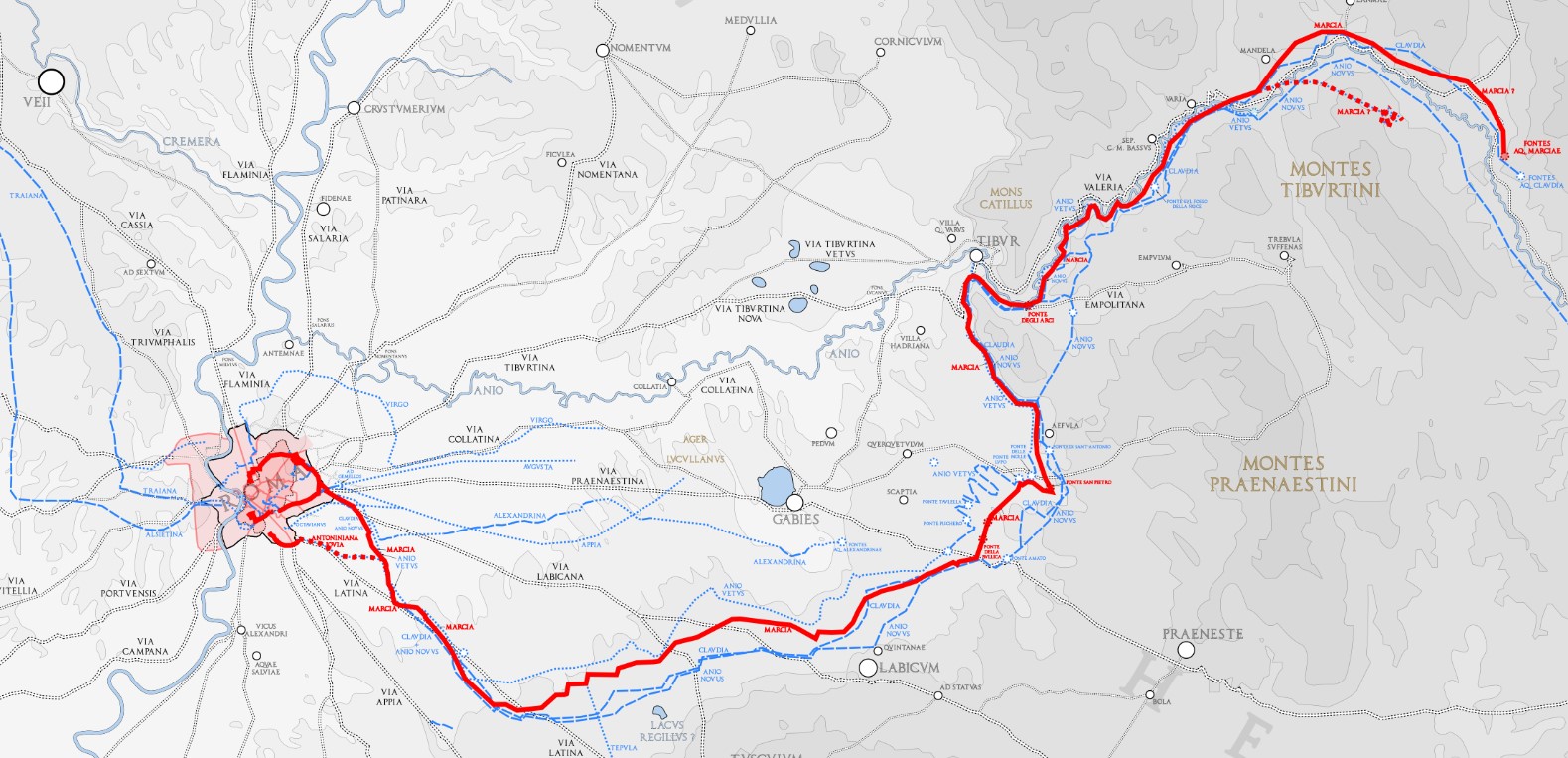

The total length of the aqueduct, from its source to Rome, was 61,710 passi (Roman steps), or 91.33 kilometers. Of this, 80 kilometers ran underground, with the remaining portion supported by arches and substructures. The aqueduct followed the course of the Aniene River to Tivoli, then turned south via an arcaded route toward the Via Prenestina. It ran alongside the Via Latina for a stretch before entering the city through Porta Maggiore (ad Spem Veterem), and finally headed north through Porta Tiburtina.

Route of the Aqua Marcia Aqueduct

After entering Rome through the Porta Tiburtina, the water was elevated on arches to its highest point at Piazza dei Cinquecento. Here, a branch (roughly following today’s Termini rail lines) emptied into a massive trapezoidal cistern—the Botte di Termini (“Barrel of Termini”)—located outside the bath complex’s southeast wall near the Porta Viminalis. This cistern, critical for maintaining the baths’ water supply, measured approximately 91 meters in length and 16 meters in width.

Trapezoidal Cistern of the Baths of Diocletian (marked in red) at Piazza dei Cinquecento, where Termini Railway Station is located.

The modern Piazza dei Cinquecento was once called Piazza di Termine (Square of End), likely referencing the cistern of Thermae Diocletianae as the aqueduct’s terminus. Water supply was ensured by a branch of the Aqua Marcia, renamed Aqua Iovia o Iobia in 286 CE to honor Diocletian’s title Iovius.

Since 1498, the cistern had been known as the Botte di Termine (theca aqua) and was divided by pillars into multiple aisles (ranging from two to five). Later, however, the water supply was ensured by reservoirs located within the complex itself, as evidenced by the transformation of Room XI in the National Roman Museum, which retains traces of waterproof lining on both its floor and walls.

From this cistern, water fed ten of Rome’s fourteen districts (regiones). The Aqua Marcia, renowned for its high quality and elevation, also supplied the Caelian and Aventine Hills via the Rivus Herculaneus, an underground conduit branching off near Porta Tiburtina. According to Frontinus (De Aquaeductu Urbis Romae), the aqueduct delivered 188,000 cubic meters daily (4,690 quinariae), remaining a vital source even in its modern reconstruction.

The Ostrogoth King Vitiges and the Siege of Rome (537 CE)

The baths functioned until 537 CE, when Ostrogoth king Vitiges cut Rome’s aqueducts during his siege. Procopius claims Vitiges’ army numbered 150,000 (likely exaggerated), but they failed to breach Belisarius’ reinforced walls. To prevent infiltration, Belisario sealed the aqueduct outlets. Most were never restored, leading to the baths’ abandonment as Rome’s population dwindled post-empire.

Rome’s first central railway station, Termini, in 1890

During the Middle Ages, the area fell into ruin. Pope Sixtus V repurposed parts of the complex, sparing the cistern. Later, Pope Clement XI (1700–1721) dismantled sections, and Pope Leo XII (1823–1829) converted remnants into a “Pia Casa d’Industria,” a workhouse for the poor. In 1876, the Botte di Termini was demolished to make way for Rome’s first central railway station, Termini—a name echoing the site’s ancient legacy.

Approximate area of the Botte di Termine, spanning from the pine trees on the left to the statue of Pope John Paul II on the right.