Like a rural fountain became the 17th century pharmacy of Rome

Rome, Italy

In the 16th century, along the Tiber River, before its waters crashed beneath the arches of the Milvian Bridge, there stood a rustic and healthful spring on the right bank, from which flowed the so-called Acqua Acetosa ("Sour Water"). It earned its name from its slightly sulfurous and tangy taste, reminiscent of vinegar.

The mineral spring, still visible today along the Lungotevere, was not yet part of the city but lay in open countryside, about three kilometers from Porta del Popolo.

This water appears to have been unknown to the ancients. The first written record dates back to 1564, attributed to Andrea Bacci, who, in his discourse on the medicinal waters springing up around Rome, noted how this exceptionally clear and light water—which had a purgative effect—was still little known.

By the early 17th century, numerous illnesses plagued both common people and soldiers. Concerned, Pope Paul V (Camillo Borghese, 1552–1621) ordered that this exceptionally pure water be channeled and piped into the city so that the many ailments afflicting his people could be treated.

The Acqua Acetosa Fountain

In 1613, he entrusted architect Giovanni Vasanzio with the task of building a modest fountain, upon which he had a plaque inscribed with the following words:

PAULUS. V. PONT. MAX. ANNO SAL. MDCXIII. PONT. IV

RENIBUS ET STOMACHO SPLENI JECORIQUE MEDETUR

MILLE MALIS PRODEST ISTA SALUBRIS AQUA

Paul V, Supreme Pontiff, in the year of salvation 1613, the 9th of his pontificate—This healthful water cures the kidneys and stomach, the spleen and liver, and benefits a thousand ills.

Plaque of Paul V Borghese and his portrait by Caravaggio (1571–1610)

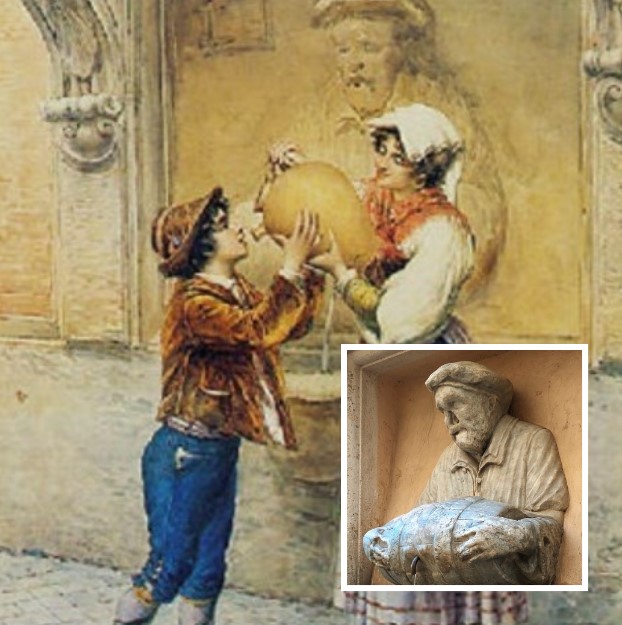

The Acqua Acetosa sprang from an iron-rich, acidic source, and due to its unique properties, Romans considered it a near-panacea—miraculously restorative and invigorating. The spring became a popular destination for outings and picnics outside the city gates, where visitors would enjoy a refreshing draught of the therapeutic water. Crowds flocked to it, and those unable to make the journey hired acquaricciari (water sellers), also known as acquaioli or acquacetosari.

These vendors would travel by donkey at night to fill around ten thousand barrels and flasks with the water, then deliver them through Rome’s streets by day, rousing the citizens with their endless, monotonous cry:

Fresca l'acqua acetosa!

Fresh sour water!

These boisterous peddlers, bare-chested and wearing straw hats, carried their wares in baskets strapped to donkeys, delivering the water in exchange for a modest fee. They transported it in straw-wrapped flasks or demijohns, sealed with straw stoppers, straight into people’s homes.

This trade flourished in the city before the restoration of ancient aqueducts. Before the discovery of Acqua Acetosa, porters drew water directly from the Tiber or the ancient Trevi Fountain. By 1615, Roman enthusiasm for the water reached such heights that many used it for cooking or diluting wine.

"The Facchino Fountain" by Carlo Ferranti (1840–1908) – A water seller dressed in typical 16th-century attire, his face weathered by time, holds a small barrel from which water flows through a spout into a semicircular basin. This is the small "Fontana del Facchino," now attached to the wall of Palazzo De Carolis on Via Lata but originally located on Via del Corso until 1872.

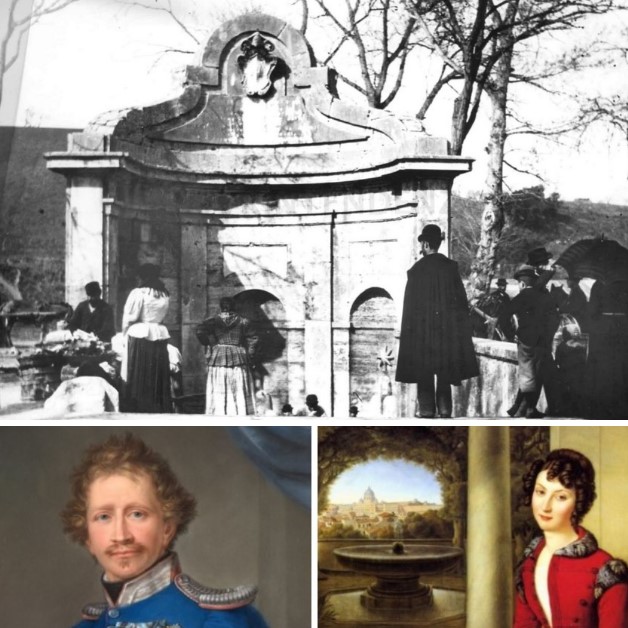

In winter, the spring saw fewer visitors due to the cold and frequent flooding from the nearby Tiber. But the rest of the year, Romans came in such numbers that decades later, Pope Alexander VII (Fabio Chigi, 1599–1667) was forced to expand the fountain for convenience. The monumental travertine fountain, set below street level, was accessed via a short staircase.

On scorching summer days, Romans and foreigners alike would flock merrily to the spring. To provide shade and cool the area, the Pope had trees planted around it. By sunrise, the fountain—gilded by the morning light—was already surrounded by countless glasses as people took turns drinking. The healthful water was gulped from cups, savored by hundreds of lips amid the bustling, cheerful crowd and the neighing of horses. Everyone drank, and drank again, to their fill. Eventually, Pope Alexander VII issued an edict to protect the fountain.

The fountain’s architecture is simple: a curved exedra divided by pilasters at the base, with three niches adorned with the Chigi family crest. Water flows from three spouts into three basins, while a pediment with papal insignia crowns the structure, bearing the inscription:

ALEXANDER VII PONT MAX UT ACIDULAE SALUBRITATEM NITIDIUS HAURIENDI COPIA ET LOCI AMAENITAS COMMENDARET REPURGATO FONTE ADDITIS AMPLIORE AEDIFICATIONE SALIENTIBUS UMBRAQUE ARBORUM INDUCTA PUBLICAE UTILITATI CONSULUIT A S MDCLXI

Alexander VII, Supreme Pontiff, so that the healthfulness of the Acidula water may be better enjoyed with a purer flow and the pleasantness of the place enhanced, provided for the public good by cleansing the spring, enlarging the structure with fountains, and adding the shade of trees, in the Year of Our Lord 1661.

Plaque and coat of arms of Alexander VII at the Acqua Acetosa Fountain, a portrait of the Pope by Giovanni Battista Gaulli (1639–1709), and the fountain as it appeared in 1665.

By the early 18th century, the water’s flow had significantly diminished, leading to long, exhausting waits for visitors, and its quality had declined. Public complaints reached the municipal authorities, who alerted the Pope. In 1712, Pope Clement XI (Giovanni Francesco Albani, 1649–1721) took protective measures: installing hydrometers to measure water levels, restoring pipes, reinforcing nearby riverbanks to prevent flooding, and other essential works—all documented on a commemorative plaque.

The hydrometer, a portrait of Pope Clement XI, and the fountain as it appeared in 1741.

In 1821, Ludwig I of Bavaria, then crown prince and future king, discovered the spring, recognizing its therapeutic properties. He became a frequent visitor and even met his great love here: Marianna Florenzi, the Marchioness of Perugia. Their 47-year extramarital affair, sustained through extensive correspondence, did not end when Ludwig had to return to Germany, their love endured despite the distance. To make his rendezvous with Marianna more comfortable, he had elm trees planted around the fountain and stone benches installed. On the right bench, an inscription remains legible:

LUDWING BAYERN'S KRONPRINZ LIES DIESE BANKE UND BAUME SETZEN, 1821

The Crown Prince of Bavaria had this bench and trees placed, 1821.

The inscription on the left bench, however, has eroded and is now illegible.

Ludwig I of Wittelsbach and the Marchioness of Perugia, Marianna Florenzi.

Since the time of Paul V, the French had prized this healthful water. When they entered Rome in 1849, they commercialized Acqua Acetosa, employing dozens of cart drivers. The acquaricciari, legs dangling from their carts, could reach more potential buyers and sell more flasks and barrels.

Acquacetosari (water sellers) in 1905.

Yet, as with all medicinal waters, doctors advised drinking it directly at the spring, as transport diminished the alkaline particles' original potency.

Rome, Via Enrico Elia