Vittoria Accoramboni, The Woman Who Defied the Pope

Rome, Italy

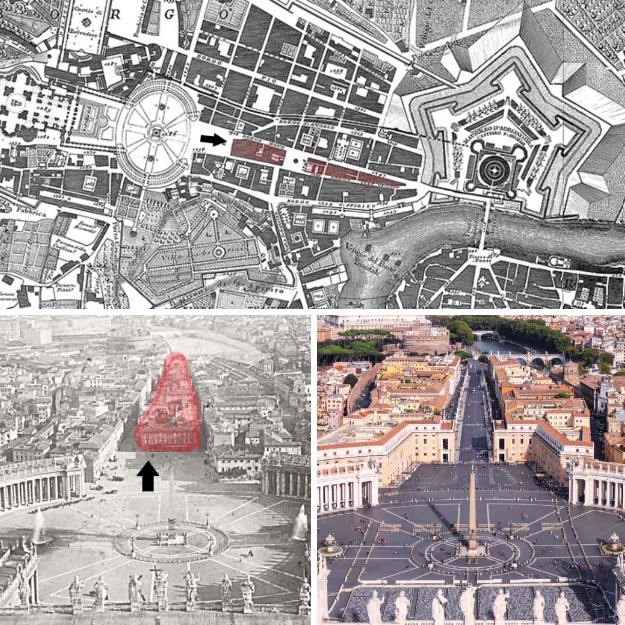

In Borgo Nuovo, there was an ancient alley known as the Vicolo degli Accoramboni, which—like the entire central section of the Spina dei Borghi—was destroyed during the construction of Via della Conciliazione between 1936 and 1940. The alley took its name from the noble family whose palace once stood there. Among its members was the stunning Vittoria Accoramboni (1557–1585), a celebrated noblewoman of the Italian Renaissance, whose tumultuous life, woven with passion and bloody intrigue, has inspired countless writers.

In the end of this story, no one truly triumphed—only death prevailed.

Paolo Giordano I Orsini, Troilo Orsini, Lelio Torelli and Isabella de' Medici

The story begins with the Medici family—specifically, with Isabella de’ Medici (1542–1576), daughter of Cosimo I de’ Medici (1519–1574), first Duke of Florence and later Grand Duke of Tuscany, and Eleonora di Toledo (1522–1562), a Spanish noblewoman and Duchess of Florence.

In 1553, when Isabella was just eleven years old, her parents arranged a marriage contract in Rome, binding her to Paolo Giordano I Orsini (1541–1585). He was the grandson of Pope Julius II’s illegitimate daughter (Felice della Rovere), held his fiefdom in Bracciano, and belonged to the powerful Orsini clan.

At sixteen, Isabella was led to the altar. She was spirited and free-spirited, her behavior often the subject of gossip. Her husband, on the other hand, was impulsive, cynical, and prone to reckless extravagance. Frequently neglected during his long absences from Florence, she was kept under the watchful eye of his husband’s cousin, Troilo Orsini, with whom she was rumored to have had an affair.

Two years after their marriage, in 1560, Pope Pius IV elevated the fiefdom of Bracciano into a duchy. By 1566, drowning in debt, Paolo Giordano was forced to sell off portions of his land.

When Cosimo I died in 1574, Paolo Giordano, seeing no further use in remaining in Florence, decided to move to Rome with Isabella while the nearby fortress of Bracciano was being restored. Though the couple lived apart, they maintained an epistolary connection until the end—Paolo always distant, his wife kept under the surveillance of his cousin Troilo.

With Cosimo’s death, Isabella lost her father’s protection. Perhaps with the tacit approval of her brother, the new Grand Duke Francesco I, Paolo—having likely learned of his wife’s infidelity—resolved to avenge his dishonor personally, committing uxoricide far from prying eyes. First, Troilo murdered Lelio Torelli, Cosimo I’s secretary and Isabella’s confidant. The following year, Don Pietro de’ Medici, Cosimo’s youngest son, took revenge and had Troilo assassinated.

Then, Paolo Giordano rid himself of his wife for good. Popular chronicles describe her death by strangulation—a noose tightened around her throat by Paolo himself, with the help of a hidden assassin, a Knight of Malta and his close friend. The official version, however, claimed she had died of a sudden illness while washing her hair, though Paolo made sure to add that she had "time to beg forgiveness for her sins."

Bracciano Castle, Pope Sixtus V, Paolo Giordano I Orsini, and Vittoria Accoramboni.

During those years in Rome, Paolo Giordano met Vittoria Accoramboni (1557–1585) at a social gathering. Though both were married, they fell deeply in love.

She came from the minor aristocracy of the Marche, a woman of extraordinary beauty and intelligence, gifted in poetry. At sixteen, she had married Francesco Peretti, nephew of Pope Sixtus V. He adored her, but Vittoria considered him unworthy of her ambitions, reproaching him for marrying her only for her substantial dowry. Soon, the dowry was squandered—Francesco, unable to sustain her lavish tastes, had spent it all. here was no entertainment or spectacle that Vittoria did not wish to attend—where all other noblewomen could only envy her jewels and elegant gowns. When her desires could no longer be satisfied, she took revenge: mocking her mother-in-law, insulting her sister-in-law, provoking quarrels, and taunting her husband’s family for being noble yet poor. She abandoned herself to lust and pleasure—first discreetly, then openly, flaunting her lovers with calculated elegance, proud of her adorned body unlike anything Rome had seen before. Her gait was deliberate, her eyes aflame, her lips ever poised between laughter and seduction.

Her affair with Orsini soon became public knowledge, and in 1581, a few years after Isabella de’ Medici’s untimely death, Paolo Giordano decided to rid himself of Vittoria’s husband. His hired assassins murdered Francesco Peretti in the street. A chilling detail was that among the killers was the victim’s own brother-in-law—Vittoria’s brother, Marcello Accoramboni, who hoped his sister might become the duke’s wife. Unsurprisingly, Paolo Giordano, who made little effort to defend himself, was immediately suspected of orchestrating the crime, already infamous for Isabella’s death.

Shunned by society, Vittoria and Paolo Giordano were forced to flee Rome, pursued by the Pope’s wrath and the hostility of the Grand Duke of Tuscany.

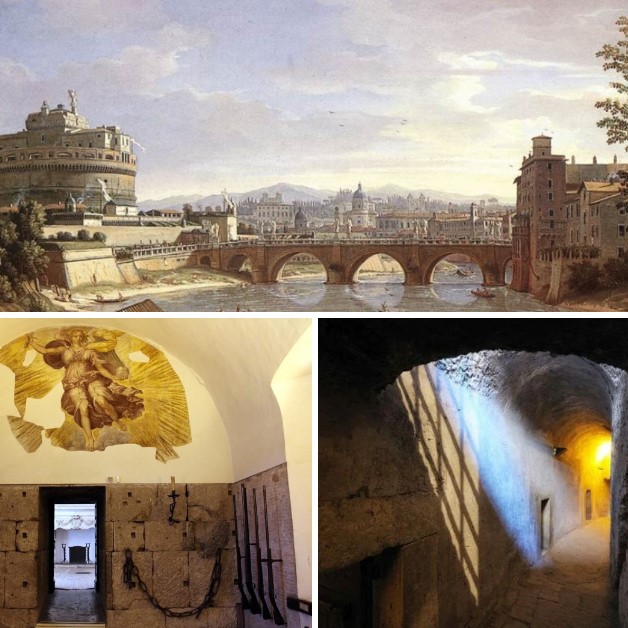

Castel Sant’Angelo and its dungeons.

Justice in Rome between the 15th and 19th centuries was often described as severe, its punishments harsh, its trials farcical, its executions macabre. The iron fist of papal tribunals had terrorized Rome’s inhabitants for centuries, yet it also contributed to the mythic status of those who defied convention—figures who ended up in the city’s most wretched dungeons, guilty of disrupting public order with their conduct, or sometimes merely their thoughts. Castel Sant’Angelo was a feared prison and site of torment, where countless souls—both famous and unknown—met their end. Ironically, it had been ceded to the papacy by the Orsini in 1365. In 1503, Cardinal Giovanni Battista Orsini died within its walls, and around 1581, Vittoria Accoramboni and her lover Paolo Giordano would also know its cells.

Highlighted in red: the 'Spina di Borgo' in the early 1900s, demolished in the 1930s. The black arrow marks the original location of Palace Accoramboni, which was torn down and rebuilt further along Via della Conciliazione. In the background, Castel Sant'Angelo can be seen.

Defiant of consequences, Vittoria and the duke married in secret. But news of their union soon reached Pope Gregory XIII, who annulled the marriage and ordered Vittoria returned to her father’s house under strict confinement.

The duke persuaded her to break the restriction, but their recklessness came at a price: Vittoria was first imprisoned in Castel Sant’Angelo, then exiled to Gubbio until 1582.

In 1583, she was finally permitted to return to Rome. From there, she traveled to Bracciano, Orsini’s fiefdom, and married him again. Yet another trial, sparked by the scandal in Rome, annulled this second marriage as well.

The situation seemed at an impasse with Gregory XIII’s death. Believing the worst was behind them, the lovers wed a third time. But the election of Pope Sixtus V—uncle of the murdered Francesco Peretti—filled them with dread. They fled to Venice and then to Salò, still under Venetian rule. There, in 1585, the duke died suddenly—perhaps poisoned by agents of Francesco de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany—leaving his duchy to his firstborn son, Virginio, and his remaining wealth to his widow, Vittoria.

Grief-stricken, Vittoria settled in Padua, but she had become a liability—no longer to the Pope, but to Lodovico Orsini. A Venetian official, lieutenant, and cousin of Paolo Giordano, Lodovico coveted his kinsman’s inheritance. First, he stripped Vittoria of all her bequeathed wealth, then had her and her brother Flaminio slaughtered by assassins. Vittoria had outlived her husband by barely a month.

The double murder did not go unpunished. After a bloody siege, Lodovico was arrested and executed by order of the Venetian Republic. He and his men were hanged in the courtyard of Castelvecchio with a vermilion rope—the customary fate of assassins and traitors.

Rome, Lungotevere Castello, 50