Aldus Manutius: How One Man Changed Reading Forever

Venice, Italy

In the 15th century, Venice was ideal for those who loved both material and intellectual life. It overflowed with all the comforts and refinements afforded by its trade: merrymaking, masks, and every manner of amusement. It welcomed kings and emperors; its nobles were esteemed as kings, and its women married powerful princes.

Venice was able to unite the West with the East. Through the precious goods it transported from there, it exchanged not only merchandise but also culture: it brought us Greek codices, knowledge of Eastern languages, and the learning that had been preserved in the East. This is why the Venetians were seen as profoundly learned men.

Among the states of Europe in the sixteenth century, the most significant in terms of maritime power, wealth, and still culture was Venice.

Commerce and governance accustomed men to observe everything and judge rightly, to be always practical, well-informed, and full of knowledge, yet eschewing pomp. The Venetian was talkative, but never rhetorical.

The strength of Venice was an idea, which is the foundation of a state's true greatness: the idea of law. Without it, neither commerce nor governance can long endure. This idea, which all obeyed blindly, bound nobles and commoners together in one great common interest. It was thus that Venice managed to stand united against arms, excommunications, envy, treachery, and conspiracies.

The first printing house of Aldus Manutius in Venice

In Rio Terà Secondo, near Campo Sant’Agostino, stands a small Gothic palazzo, a 15th-century construction where Aldus Manutius lived and operated his famous printing house around 1490.

Florentine Miniaturist (?) active in Venice at the beginning of the 16th century. Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Opere, Venice, Aldus Manutius, 1501. Dedication by Aldus Manutius to Marin Sanudo and Frontispiece with Portrait of Horace. Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana.

Aldus Manutius was born around 1450 in Bassiano (a town about sixty kilometers from Rome). After studying Latin and Greek in Rome and Ferrara, he retired to Mirandola near Giovanni Pico in 1482; in 1483 he was in Carpi, tutor to Prince Alberto Pio, who later granted him permission to add the Pio family name to his own.

Bassiano, an ancient village along the Southern Via Francigena route

He moved to Venice before he was forty, after having stayed in Ferrara, where at the university he was a pupil of Battista Guarino, one of the foremost scholars and teachers of ancient Greek of the time, and in Carpi, where he served as tutor to the young princes Alberto and Lionello Pio and established a fruitful intellectual and personal relationship with their famous uncle: the humanist Giovanni Pico della Mirandola.

At that time, Venice had become the emporium of trade and one of the European centers of the technological revolution of the era: printing. In 1469, Johannes de Spira (Johann of Speyer) brought the first presses to the Lagoon, inspiring by his example dozens of workshops from which hundreds of books and pamphlets emerged daily, bound for all of Europe and appreciated for their excellent quality and modest cost. These were mostly large ecclesiastical or legal books, destined for a market ranging from wealthy Bavarian monasteries to English parishes: private libraries were still extremely rare.

So, in Venice, Aldus – together with another famous printer, Andrea Torresani of Asola (Mantua), whose daughter he would marry, and the wealthy patrician Pierfrancesco Barbarigo, acting as financier – came to live and brought his craft to a perfection unsurpassed by anyone.

It is in this environment that a humanist and teacher, a grammaticus no longer in his youth, conceived an idea both crazy and visionary: to collect and publish the best of world culture through a series of books of exquisite craftsmanship, clear in form and pleasing to the sight and touch.

He began with the classics of Greek literature and philosophy, published strictly in the original language. The monumental five-volume edition of Aristotle's works (1495-98), though incomplete, would become one of the foundations for the subsequent study and teaching of the Philosopher par excellence. A work which, according to book historians, rivals in importance even the Gutenberg Bible (printed starting in 1453): until then, Greek authors had been studied in medieval Latin translations, often of poor quality.

These were followed by the editiones principes (i.e., the very first editions ever printed) of authors like Aristophanes, Sophocles, Xenophon, Demosthenes, and many others.

His noble aim was to safeguard and transmit the entire heritage of ancient culture, especially after the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453: Venice, full of Greek refugees and manuscripts, was the ideal place to recover sources, establish definitive texts, and recompose and consolidate what would become the corpus of classical thought transmitted down to today.

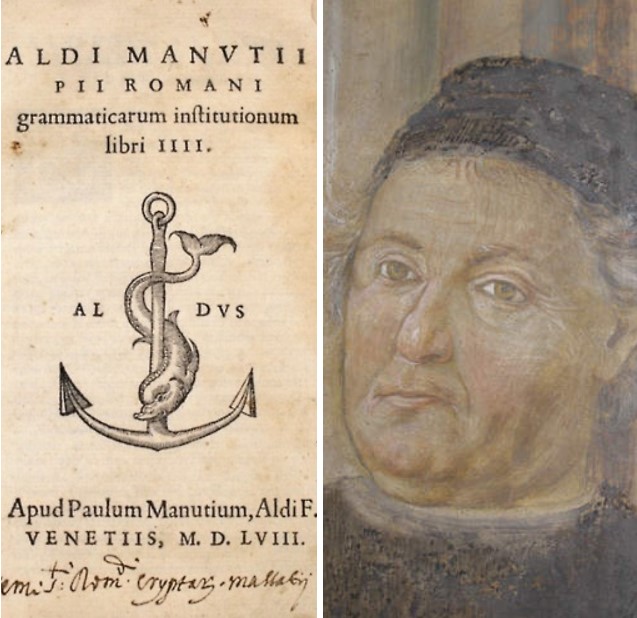

Aldus Manutius in a fresco by Bernardino Loschi. Castello dei Pio, Carpi (Modena) and the famous printer's mark of the Anchor and Dolphin.

The book is an object born in antiquity but which acquired its current form in a very specific place and time: Venice between the 15th and 16th centuries, thanks to Aldus Manutius, the first modern publisher.

Among ancient and modern printers, Aldus Manutius holds the place of honor: he is considered the greatest typographer of his time and the first publisher in the modern sense. He popularized books by printing them in small formats; thanks to him, editions were prepared with the utmost diligence and great scholarship; he devoted his entire life to disseminating the classics and all those books best suited to general culture.

Aldus Manutius was a learned man: he knew Latin and Greek, and was also versed in the sciences and literature. New to typography, he dedicated himself to it with the most ardent desire to advance it.

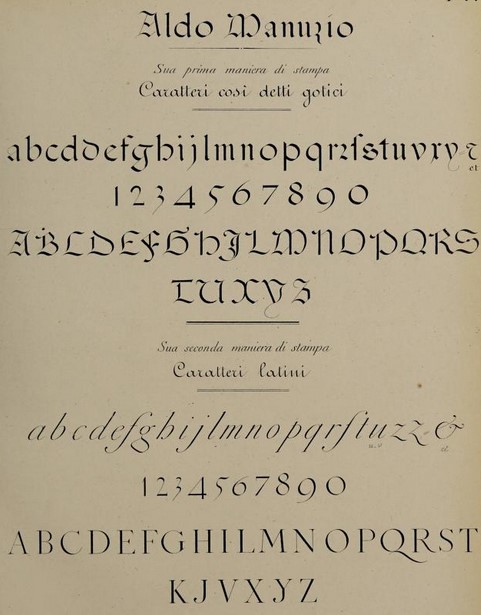

He worked tirelessly, publishing books of great interest. It is to him that we owe the revival of printing, which, from Gothic typefaces, sometimes of unpleasing forms, returned to Roman characters.

Indeed, in 1501, Aldus introduced the use of the slanted Roman typeface, also known as 'Italic' or 'Aldine', inspired by the handwriting of Petrarch, who was also an excellent calligrapher.

This new typeface was executed by Giovanni da Bologna (Francesco Griffo), a skilled engraver who had previously been commissioned by Manutius to engrave other typefaces used earlier in his printing house. Some scholars believe Aldus himself designed and cast this type.

Typefaces used in the first and second printing styles practiced by Aldus Manutius, with their respective lowercase and uppercase alphabets.

Aldus Manutius was a humanist, publisher, and printer who gave European humanism excellent editions of Greek, Latin, and Italian classics, marked from 1502 by the famous printer's mark of the anchor and dolphin, later also adopted by his successors.

In his early editions, he signed himself in Latin as Aldus Mannucius; from 1493, Manucius; and from 1497, Manutius, which was later Italianized by posterity to “Manuzio.” It is likely his original name was “Mandutio” (Mandutius).

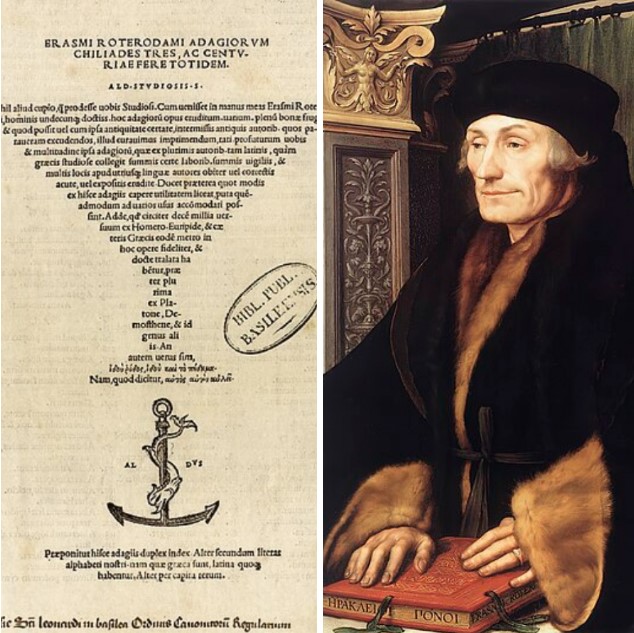

The Dutch philosopher Erasmus of Rotterdam, and his work 'Adagia' published by Manutius.

The Dutch philosopher Erasmus of Rotterdam, who came to Venice in 1508 to finish his Adagia in the quiet of the lagoon and have them published by Aldus, was a guest of the family. Aldus was nearly sixty at the time, but his wife was very young and had made him the father of three sons and a daughter.

The printing house had been running for several years and work was plentiful, but expenses were mounting: the press cost Manutius about two hundred ducats a month; moreover, following Venetian custom, he provided room and board for copyists, translators, proofreaders, and workers. To turn any profit required the strict administrative oversight of Torresani (his father-in-law), who, according to Erasmus, cared only for making money and devised a thousand schemes to save it:

...he watered down the wine, bought spoiled wheat to make bread, fed the workers lettuce, and served guests a thin beef broth and cheese hard as stone.

Erasmus, a philosopher and humanist but also a hearty eater and indiscreet lover of good wine, claimed he suffered not only hunger but also cold and sleeplessness. He recounts that the house of Manutius, the prince of printers, was poorly insulated and drafty in winter, and in summer so full of fleas and bedbugs that one couldn't sleep a single hour.

Perhaps the philosopher exaggerated, but there must have been some truth to it, for Manutius parted ways with his father-in-law and opened his own printing house at San Paterniano in the "Rio Terà" near the church that then stood on the site where the Cassa di Risparmio building (Campo Manin) stands today.

The position of the church of San Paterniano at the eastern end of what, with the late 19th-century restructurings, would become Campo Manin. Top left shows the church and bell tower before demolition. On that occasion, the well was removed, while the ancient bell tower and the church of San Paternian were demolished. Campo San Paternian was enlarged and restructured to house the monument to Daniele Manin, which gave the square its new name. The surrounding buildings were rebuilt, including the one destined to become a bank headquarters (the modern building at the end of today's square). Where the bell tower stood, today stands the statue of Daniele Manin.

In the new house, Manutius continued to publish his splendid editions, and it was here that towards the end of 1514 he dictated his will with this curious clause:

I leave to Maria, my dearest wife, besides her dowry, five hundred ducats, on this condition: that one year after my death, she must do one of two things: either become a nun of observance in a convent of good repute, or marry a man from Carpi, Asola, or Ferrara, but not from other places. Otherwise, I wish her to have nothing of my goods and estate.

Aldus Manutius died the following year, aged only sixty-six, after a long life of work and toil. His last wish was to be buried in Carpi. The funeral was held in the Church of San Paterniano, where his body was surrounded by many books. After the funeral, a eulogy was delivered in his praise. The burial place of this learned and famous master of the typographic art was never known.

His wife, Maria Torresani, not yet thirty, settled in Ferrara with her young children. Paolo, the youngest, was just three. Feeling no calling for monastic life, she preferred marriage to a wealthy merchant from Carpi. Paolo later became the continuator of his father's celebrated printing house and also became a famous printer and a most accomplished scholar.

Rio Terà Secondo (Venice)