Arsenic and poets: A Renaissance Whodunit

Modena, Italy

The death of the great philosopher and humanist who revolutionized modern thought, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494), buried in the Church of San Marco in Florence, is a historical mystery. His bones were discovered by Father Chiaroni in 1933 alongside those of Angelo Poliziano (1454-1494) and his friend Girolamo Benivieni (1453-1542).

In 2018, for the sixth time in roughly 500 years, the casket embedded in the western wall of the church was reopened. Tissue and bone samples taken from the remains of the two friends Poliziano and Pico confirmed that both died from arsenic poisoning at levels 50 to 100 times higher than the human body can tolerate.

Detail from 'The Miracle of the Chalice' by Cosimo Rosselli, Saint Ambrogio Church, Florence, showing figures traditionally identified as Pico della Mirandola (left), Angelo Poliziano, and (possibly) Alberti or Ficino - Portrait of Girolamo Benivieni (c. 1520) by Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio.

We have lived renowned, O Hermolaus, and so we shall live hereafter, not in the schools of grammarians, not where boys are taught, but in the gatherings of philosophers and the circles of the wise, where matters are neither handled nor discussed concerning the mother of Andromache, the children of Niobe, or such trifles, but concerning the principles of things human and divine.

- Pico della Mirandola

Recent investigations revealed intriguing details:

• The remains of Girolamo Benivieni and the great Pico della Mirandola were placed side by side within the same coffin;

• Pico was exceptionally tall (187-188 cm) – significant given the shorter average height in the 1500s – and engaged in intense physical activity, which particularly engaged the upper left side of his body. He had also suffered a severe fall, evidenced by a fusion of the right sacroiliac joint in his pelvis.

'Adoration of the Magi' by Sandro Botticelli (1475), Uffizi Gallery. Figures identified include Giuliano de' Medici, Angelo Poliziano, and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola

The differing conditions of the remains indicate that Benivieni's body was placed in the coffin where it still lies at the time of his death, and that Pico della Mirandola's bones were later transferred into the same coffin. This likely occurred when Benivieni was buried, nearly fifty years after Pico's death.

Tombs of Giovanni Pico, Girolamo Benivieni, and Angelo Poliziano with the statue of Savonarola in front, Basilica of San Marco, Florence - Opening of Pico's coffin in 2007 and his 2018 facial reconstruction.

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola was one of the noblest figures of the Renaissance, one of the most splendid ages in the history of Italian wisdom and European civilization. Nicknamed the 'phoenix of intellects' for his erudition, he was greatly admired by many illustrious men of his time who became his friends, including Lorenzo de' Medici and Girolamo Savonarola. If not in refined literary taste and Latin/Greek letters, he was certainly superior to all in philosophical erudition and the study of Oriental languages; his prodigious intellect earned him immense fame throughout Italy and beyond.

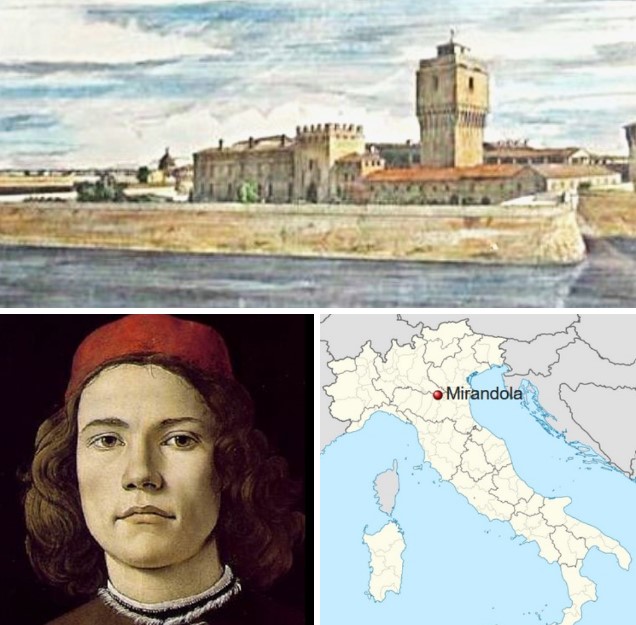

Mirandola (Modena) and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola

Much information about Giovanni Pico comes from the Life written by his nephew, Count Giovanni Francesco Pico, a learned 15th-century humanist. Giovanni was born in 1463 in Mirandola to Giovan Francesco I Pico and Giulia dei Boiardo. At his birth, a flame in the shape of a circle was reportedly seen above the new mother's bed – an evident sign the newborn was destined to illuminate the world. Mirandola (now a town about thirty kilometers from Modena) was a very small independent state, having gained independence in the 14th century. In 1414, Emperor Sigismund granted it the fief of Concordia, and the Pico family ruled it as independent sovereigns rather than noble vassals. His noble family was closely related to the Sforzas, Gonzagas, and Estes.

Giovanni was the youngest of five children (three boys and two girls) and was orphaned of his father at age two. At five, he experienced the precariousness of princely life when his brothers fought for supremacy over their small domain: Galeotto imprisoned his other brother, Anton Maria. After two years in prison, Anton Maria was released but stripped of his inheritance, forced to seek refuge with the Pope and the Duke of Calabria. Only through great effort and the intervention of the Pico brothers' brother-in-law, Ercole I of Ferrara, was a settlement reached. Galeotto gained control of Mirandola and its territory, and Count Anton Maria was allowed to share power, ensuring the brothers did not prejudice the inheritance due to their ten-year-old brother, Giovanni.

His mother first directed young Giovanni towards studies. From his earliest years, he revealed a prodigious memory and precocious intellect: he was quick to grasp any instruction given or could learn a poem with astonishing speed. He was also shy, of a gentle and yielding disposition, and inclined to mysticism. Therefore, his mother Giulia decided to steer him towards becoming an Apostolic Protonotary ('first notary,' responsible for drafting apostolic acts of the Roman Curia). As soon as her son reached the age of ten, the Countess solemnly celebrated his investiture.

Medieval university students. Fragments from the Tomb of Giovanni da Legnano (d. 1383) by Pier Paolo dalle Masegne, Civic Medieval Museum of Bologna, originally in Basilica of San Domenico.

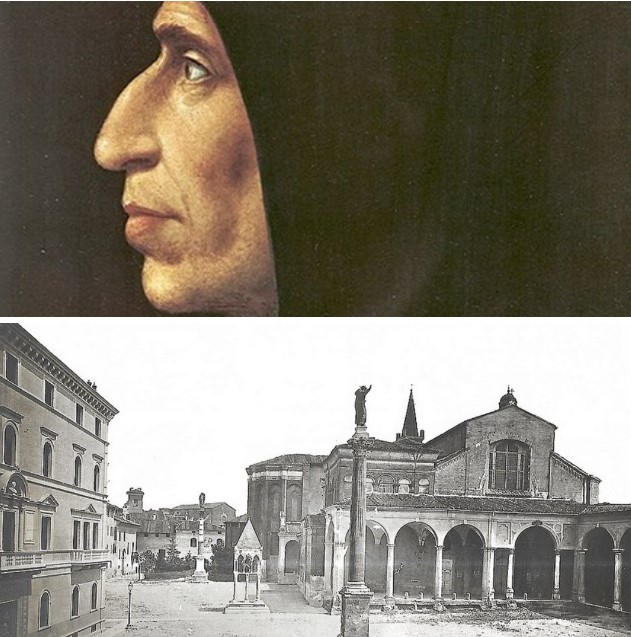

At 14, she sent him to the University of Bologna to study canon law, where he continued his studies for seven years. The lively city of the Goliards, through its university, could be considered the conduit through which humanist ideas passed from Italy to Europe. Students gathered there from every region of Italy and beyond the Alps, forming corporations with their own statutes. The Church of S. Domenico was where the corporations of jurists usually assembled. Among the preaching friars dedicated primarily to study, one attracted Pico's attention: Girolamo Savonarola, then a young twenty-five-year-old already emaciated by fasting and abstinence. It's unclear if they formed a bond then, but later they were linked by mutual esteem.

Portrait of Girolamo Savonarola (1498) by Fra Bartolomeo (1472–1517) and the Basilica of San Domenico

At 15, while studying in Bologna, his mother died. Countess Giulia, who had moved to Bologna to be near her beloved son, was struck by a fatal illness. Her body, transported to Mirandola the following day, was buried beside her husband's in the Church of S. Francesco (one of Italy's earliest Franciscan churches, perhaps contemporary with or slightly later than the Church of S. Francesco in Bologna).

At 16, Pico, perhaps feeling unsuited to canon law, decided to go to Ferrara to his sister and brother-in-law Duke Ercole I. Ferrara was then one of Italy's most populous and wealthy cities, and there he delighted in attending the school of rhetoric and poetry run by Battista Guarino. Despite his affection for Ferrara, where he formed friendships with prominent figures in the literary world, his restless character and hunger for knowledge soon made him yearn for other cities.

At 17, like all humanists of the time – whose greatest joy was seeking out new codices, rummaging through convents and libraries, discovering some new volume – he decided to move to Padua. The city was then the center of the intellectual movement in Northeastern Italy, and for philosophical teaching, it was essentially one with the University of Bologna where Pico had studied. There he studied Greek, Aristotelian philosophy, and its Greek, Arab, and Latin commentators. The direction of studies pursued in this city and the student environment seemed to satisfy him greatly. Girolamo Ramusio testifies to the student life then lived in Padua in his Latin poems dedicated to his friend Pico, with whom he shared a love for studying Oriental languages and adventurous living.

Everything scholastic and medieval in the Theses and other philosophical works of Pico stems from these years of study at the University of Padua, which continued medieval traditions longer than any other institution.

During his two years of study in Padua, he often returned to his native Mirandola, appreciating its quiet and simple country life, and loved inviting friends and teachers there. But in those years, the peace of the castle was shattered by the horrors of a fratricidal war between Venetians and Ferrarese. Mercenary soldiers, during their raids, assaulted and robbed the prosperous peasants of the Po Valley. The vision of a reality steeped in blood, so distant from the ideal gentleness rendered by his humanistic studies, likely contributed to Pico abandoning any thought of participation in political life and choosing between the unstable career of a prince and the mission of a scholar – the latter offering a surer and more lasting path.

At 19, to be freer to pursue his studies, Giovanni declined any involvement in his own affairs and entrusted the administration of all his possessions to his elder brother. Thus, he set off for Pavia with his Greek teacher, though his stay was brief.

The Beginning of Pico's Literary Life

At 21, after visiting Pavia again and staying in Carpi with his sister Caterina and his young nephew Alberto Pio (whose tutor was his friend Aldo Manuzio, Pico moved to Florence and immediately entered the Platonic circle revolving around Marsilio Ficino.

At 22, he moved to Paris as a guest of the Sorbonne, then an international center of theological studies, where he met cultured men like Lefèvre d'Étaples, Robert Gaguin, and Georges Hermonyme. He became famous throughout Europe for his prodigious memory, said to be so extraordinary that he memorized many literary and scientific works underpinning his vast encyclopedic knowledge. He could recite the Divine Comedy backwards, starting from the last line – a feat he reportedly could perform with any poem he had just finished reading. Today, the epithet 'Pico della Mirandola' is still used for anyone gifted with an excellent memory.

At 23, he returned to Italy, to Rome, where he prepared 900 theses for a universal philosophical congress, ready to pay the travel expenses for all scholars who came to question him. His goal was to demonstrate a pious philosophy capable of ensuring peace and concord among all schools, but the congress never took place.

Meanwhile, he devoted himself entirely to studying Hebrew, Chaldean, and Arabic languages, especially books presented to him by a Sicilian Jew, purchased at great cost. These were treatises and books of the Kabbalah, for which he developed an overwhelming passion, believing it contained profound wisdom and secret testimony to Christian truths. Indeed, it seems Sicilian Jews possessed many books in their synagogues, schools, and private homes; so much so that during their harsh expulsion in 1492, they asked Viceroy de Acugna if they could take them. This was also granted to the Jews of Malta. He himself wrote, fervent about the secret books he had acquired, that day and night he was occupied studying them, to the point of nearly losing his eyesight. He immersed himself in the study of Jewish Kabbalah because he thought he would find the foundations of the deepest wisdom contained in the Bible.

Painting by Giorgio Vasari (c. 1556) in Palazzo Vecchio, Florence. Giovanni Pico is the fourth figure to the left of Lorenzo de' Medici, with Angelo Poliziano behind him.

At 25, Pico faced accusations of heresy, forcing him to flee to France where he was even arrested by agents of Charles VIII. Freed through the intervention of Lorenzo il Magnifico, he became Lorenzo's guest in a villa in Fiesole. There, he resumed frequenting Marsilio Ficino's Academy and composed his major works.

During those years, he grew closer to Savonarola, whom he had urged Lorenzo to call to Florence, and focused particularly on sacred studies.

His incredible industriousness kept him occupied with multiple works simultaneously: he proved a miracle of doctrine and erudition, and a rare example of activity in composing works all weighty with richness of doctrine and speculative depth. This doctrine was wonderfully combined with religious piety, towards which he turned his soul with ever-increasing fervor. In the flower of youth, he renounced not only his princedom but even his wealth to devote himself to studies and piety, and to uphold Christian doctrines and the Church with his philosophical and theological writings.

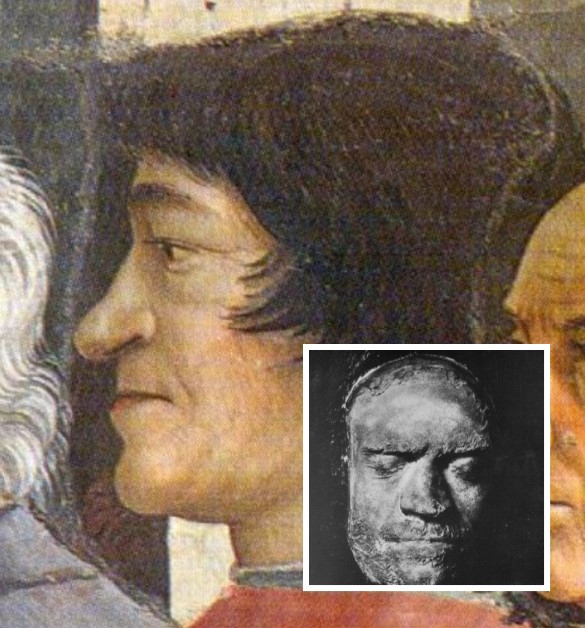

Cast of the Dead Mask of Lorenzo de' Medici by Orsino Benintendi (1440–1498) - Lorenzo dei Medici on 'Confirmation of the Franciscan Rule' (c.1485) by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1448–1494), in Basilica of the Holy Trinity (Cappella Sassetti), Florence.

Death of a Genius

At 31, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola was working on a treatise aimed at refuting all superstitions. He only managed to complete the section against astrology when he was suddenly struck by a deadly fever that brought him to the grave in thirteen days. He died in Florence at thirty-one years old, at the height of his fame; fortified by the sacraments of the Church, he confirmed his faith, spoke of celestial visions to his nephew Alberto and the Dominican friars assisting him, and adding bequests to his family and household, legacies to the poor of the Florence Hospital and his nephews, he passed away peacefully amid the lament of the entire city, indeed all of Italy, and even Charles VIII of France, who was then entering Florence and ordered splendid funerals to be held for the great man.

Before his death, Giovanni had shown his intention to enter the Order of Preachers (Dominicans) as soon as he finished the works he was engaged in or contemplating; as Friar Girolamo Savonarola publicly recalled after his death in the Church of Santa Reparata. Leandro Alberti narrates that Giovanni received the Dominican habit, in which he was buried. Just as Dante was clothed in the Franciscan habit at death, so Giovanni was clothed by the famous Fra Girolamo in the Dominican habit and buried in San Marco, fulfilling in death the vow he could not satisfy in life.

Giovanni died suddenly at 31. On the very day Pico was dying in Florence, King Charles VIII of France was conquering the Kingdom of Naples with a mighty army. Having defended Pico in the past against Pope Innocent VIII, the Valois king, learning of Pico's condition, sent two doctors from his retinue to visit him, though by then his fate was sealed. Alberto Pio, Lord of Carpi and son of Pico's sister, attended him on his deathbed; his other beloved nephew Gianfrancesco Pico, son and heir of the Lord of Mirandola and brother of Giovanni, Galeotto, did not arrive in time to comfort him.

Pico was buried in the cemetery of the Dominicans within the walls of the Convent of San Marco in Florence. The philosopher's coffin remained unburied for a long time, propped against a wall under the portico of the cemetery cloister, without inscription or insignia. It received a proper burial only in 1542, thanks to the offer of a shared niche by Girolamo Benivieni, the inconsolable friend who, when Pico died, nearly committed suicide in despair and wished to be buried beside him.

After Pico's death, rumors spread that he had been poisoned, and that the instigator was Piero de' Medici, who feared his friend Pico's growing closeness to Savonarola's ideas and governance.

After Lorenzo il Magnifico's death, his son Piero rose to lead Florence. Despite his upbringing, he proved unequal to the role: within less than two years, the peace guaranteed by his father vanished. At that point, Charles VIII, King of France, made his descent into Italy, obtaining four Tuscan strongholds from the Florentine ruler, thus sealing the end of the Medici. According to some contemporary chroniclers, Pietro was so servile that he knelt to kiss the King's slippers. He bowed to the powerful invader, acceding to every demand, including the exaction of one hundred and twenty thousand gold florins to fund his military campaign. This attitude led to a popular revolt in Florence led by Savonarola, always hostile to the Medici but previously restrained by the Magnificent's prestige.

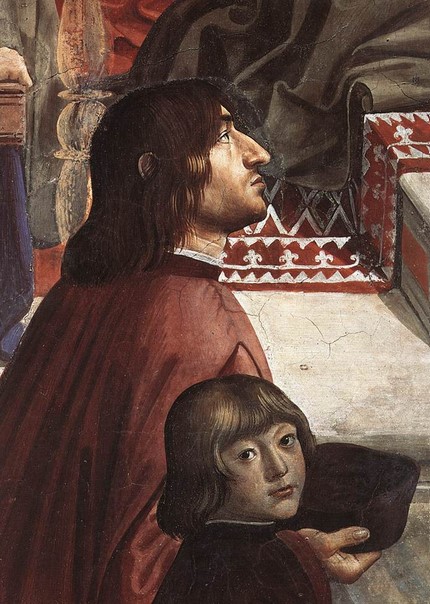

Angelo Poliziano and Piero de' Medici on 'Confirmation of the Franciscan Rule' (c.1485) by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1448–1494), in Basilica of the Holy Trinity (Cappella Sassetti), Florence.

Nel 1475 il Magnifico designò Poliziano come precettore del figlio, Piero, e lo invitò ad alloggiare a Palazzo Medici affidandogli anche l'incarico di suo segretario personale.

Why did Piero de' Medici come to hate Pico and Poliziano so intensely as to have them killed?

Poliziano contracted a fever that led to his death two months before his friend Pico: the doctors of the time spoke of poisoning. The expedition of Charles VIII of France had rekindled hostility towards the Medici, and the preaching of the Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola was inflaming the Florentines.

According to Marino Sanuto, a contemporary chronicler, Piero hated Savonarola, who at that time governed Florence – a position Savonarola had attained partly through the advocacy of Lorenzo. Pico and Poliziano had championed Savonarola's cause, who subsequently expelled Piero from Florence. Piero's hatred also grew because of the high regard in which his father, being a fine humanist, held the two intellectuals.

Furthermore, Sanuto, in his diary, recounts how Cristoforo da Casalmaggiore, Giovanni Pico's personal secretary who had strong ties to Piero, under interrogation confessed among other admissions to hastening his master's death because Pico had left him a substantial inheritance in his will. He claimed his brother Martino helped him poison both Pico and Poliziano.

Therefore, the same hand and the same arsenic likely stand behind the deaths of the two intellectuals, with the same instigator (Piero). However, the double murder could also have had other instigators, such as Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia), who was fighting Savonarola, or the philosopher and astrologer Marsilio Ficino, accused of witchcraft and necromancy by Pico and Poliziano.

Via Circonvallazione, 184, Mirandola (Modena)