Mystery of the Skull on Rome's Palatine Hill

Rome, Italy

We now know that the Palatine Hill was stably inhabited and occupied since the Iron Age (10th-9th century BC). Indeed, preserved on the hill’s summit and slopes—precisely where ancient historical tradition places the mythical founding of Rome—are the remains of protohistoric huts, used until the end of the 7th century BC.

Among these huts, in the southwestern corner of the hill called Cermalus, stood the so-called Hut of Romulus, traditionally considered the city's founder. Not by chance, this hut and its adjacent structures were spared by later constructions. As Plutarch and Dionysius of Halicarnassus recount, they were preserved for centuries in their original state through careful restorations.

Reconstruction model of the Germalus huts

The huts were very simple oval-shaped structures, with walls made of clay, straw, and reeds. Their roofs were supported by wooden posts driven into the tufa rock. Inside was a single room featuring a central hearth, whose smoke escaped through a small roof vent, while other windows might have been located on the sides. In some cases, a small porch stood before the entrance, consisting of two posts and a sloping roof—a feature suggested by postholes found in front of doorways. Grooves along the perimeter helped drain rainwater.

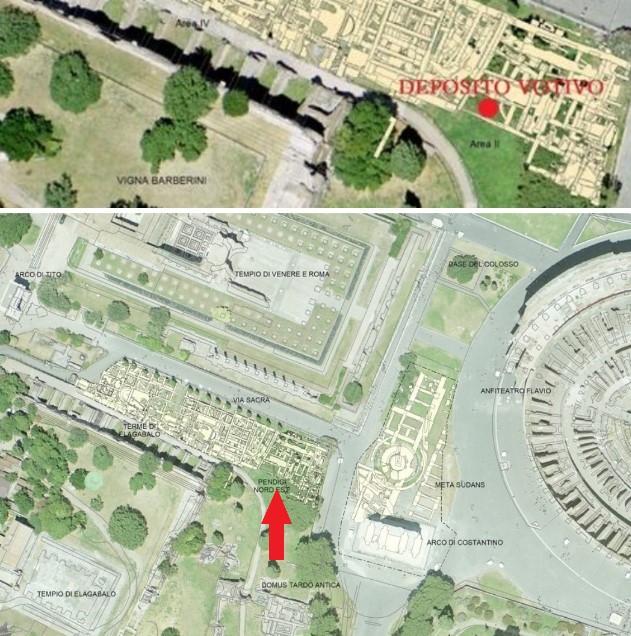

The Votive Deposit

The Curiae veteres (Ancient Curiae) was a sanctuary in ancient Rome, located along the northeastern side of the Palatine. Tradition attributes its foundation to Romulus, where citizens gathered twice a year for communal feasts.

Within the sanctuary, votive deposits linked to centuries-old rituals have been identified. Communal meals, offerings to the revered deity (Juno Curitis), and cultic acts associated with ongoing construction and destruction have left impressive traces at the site. As they became too small for the population’s needs, they were replaced by the Curiae Novae (New Curiae).

Bucranium on the Ara Pacis Augustae.

According to sources, Augustus was born both in curiis veteribus (in the Ancient Curiae) and ad capita bubula ("at the heads of oxen"). These two sites must therefore have been adjacent. They were so well-known that they served as topographical landmarks: Augustus’ birthplace, for example, was located ad capita bubula. The name likely derived from an ornamental frieze composed of bucrania (ox skulls). However, Varro uses bubulum to mean "herd of oxen," and since the place name is among the oldest, it might indicate a cattle-grazing area predating Rome's foundation. Indeed, bovine skulls (bucrania, so frequently depicted in Roman monuments) were displayed on fences before being buried as remains of sacrifices and subsequent feasts.

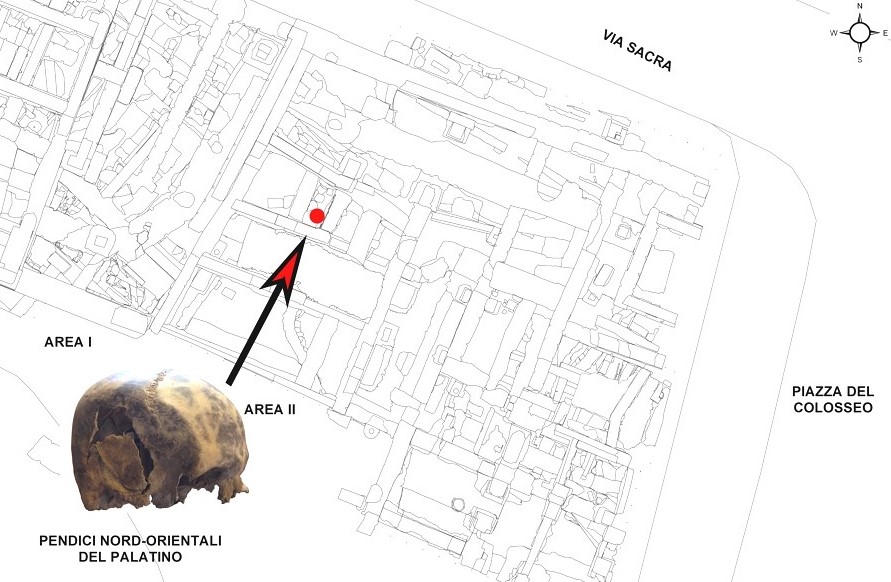

The Skull's Discovery Site

During archaeological excavations near the Curiae veteres , a human skull was found alongside numerous ox heads and a newborn buried in a terracotta pot without other skeletal remains. The olla (pot) containing the infant’s body likely ended up there during the sanctuary's reorganization and came from a demolished building. Burying a child within the city of the living was not unusual. Similar burials were common in ancient Roman spaces over time; examples have also been found beneath the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina in the Forum.

Over time, the sanctuary underwent renovations but remained a venerated site. Architectural remains from previous structures and votive offerings were buried in ritual pits. Fragments of brightly painted ornamental terracottas, dating back to the Regal period, have been recovered. The skull, however, was found in a later layer dated to the 5th century BC, when the cult site was still fully active. We know that if a skull was removed from a burial, it often became an object of worship for social groups claiming descent from the deceased, believing this would secure their ancestor’s protection. Bones removed from skeletons were also buried separately and used as personal ornaments or amulets—thought to hold magical powers if from "special" individuals: prophets, extraordinarily courageous people, or those with prodigious physical anomalies. Radiocarbon dating confirms a possible timeframe between the 8th and 5th centuries BC. Thus, either the skull belongs to an earlier era and was haphazardly reburied after being uncovered during construction, or it is contemporary with the sanctuary and was publicly displayed. Perhaps it was a trophy head from an enemy or a figure linked to the community gathering there.

The Skull Found on the Palatine

The skull belonged to a man aged 30-35, blind in one eye, and showed peculiar features: the jaw, incisors, and canines were missing, while two molars had been regularly carved, and the bones behind the ears were cleanly sawn off. These modifications likely occurred post-mortem to mount the skull on a support as a trophy.

However, ancient writers recounting Rome’s origins and development make no mention of human trophy skulls on the Palatine; they only reference bovine remains, which were certainly abundant.

Skull found in France with a knife still embedded, belonging to a Roman soldier killed during the Gallic Wars (52 BC). Displayed at the Rocsen Museum, Córdoba, Argentina.

The practice of displaying enemy heads—especially those of kings and commanders—was widespread among Celtic populations, particularly the Gauls. Many skulls pierced by nails or with perforated crowns have been found in France, Spain, and Germany.

Historical accounts include:

• Gauls hung famous enemies' heads and bloodstained weapons taken from foes in their homes. Heads were embalmed with cedar oil, placed in baskets, and shown to strangers (Diodorus Siculus).

• During Augustus’ time, Gauls nailed severed enemy heads to their door lintels (Strabo).

• Gallic warriors hung legionaries' heads from their horses or impaled them on spear points while singing menacing war songs to terrify Romans (Livy).

Records of Romans decapitating enemies as a sign of major victory are scarce but occurred, with heads preserved in honey, wax, or bandages:

• Romulus beheaded Acron, King of the Caeninenses.

• In 222 BC, Consul Marcus Claudius Marcellus beheaded Viridomarus, leader of the Insubrian Gauls.

• Mark Antony displayed Cicero’s severed head on his desk; his wife Fulvia allegedly pierced its tongue with a hairpin.

• Emperor Maxentius’ head, defeated by Constantine at the Milvian Bridge (312 AD), was paraded by victorious soldiers and sent to Africa (his power base).

• Pompey’s head was sent to Julius Caesar.

• Brutus’ (one of Caesar’s assassins) head was sent to Rome but lost in a storm.

A parallel market even emerged for famous individuals' skulls. For example, after Gaius Gracchus’ death, his head was sold for its weight in gold. To increase its price, his brain was replaced with lead.

Rome, Temple of Elagabalus