From Velitrae Usurers to Palatine Gods: Augustus' Invented Dynasty

Rome, Italy

Velitrae (modern Velletri) was the ancestral home of the family of Octavian (63 BC–AD 14) and his sister Octavia. This origin story forced the Princeps to invest heavily in image-making and propaganda to convince the public he was born on Rome’s Palatine Hill.

The family belonged to the equestrian branch of the gens Octavia, long established in this ancient city of the Alban Hills, as confirmed by Latin inscriptions and sources. Equites (knights) ranked just below senators in Roman society. Honored by the state with a warhorse for military service, they formed the entrepreneurial class, thriving in trade and craftsmanship. As provinces were established, equestrians secured major public contracts and tax-collection rights, while also gaining direct political power through offices like Praetorian Prefect (commander of the emperor’s bodyguard) and Prefect of Egypt (the first province entrusted by an emperor to an equestrian).

Thus, like many late Republican municipal families, the Octavii reinvested agricultural profits into finance—particularly high-interest moneylending. Though deemed dishonorable by the nobilitas, these ventures swiftly propelled them from bankers to emperors.

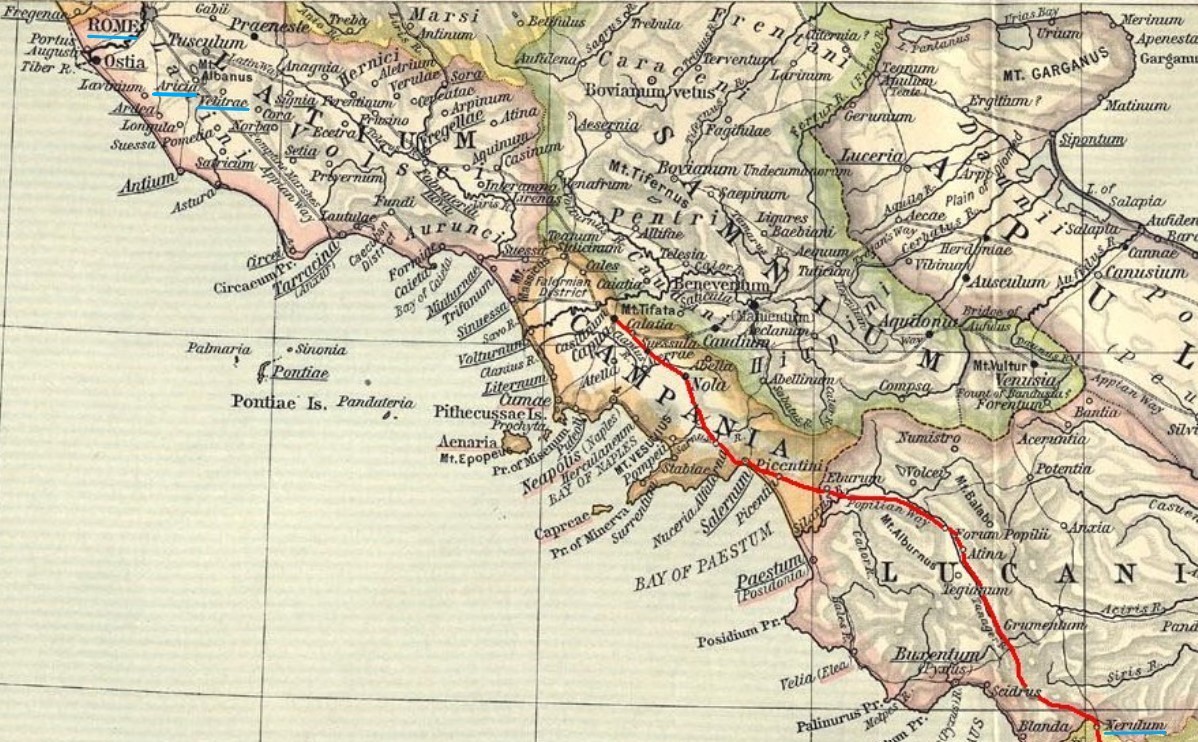

Rome, Aricia, Velitrae and Nerulum

Rome, Aricia, Velitrae, and Nerulum

Not everyone praised Augustus’ lineage. Critics disparaged them as usurers: a grandfather who was a moneychanger from Nerulum; a father who was an argentarius (banker and usurer); and a great-grandfather, a freed rope-maker from Thurii. It was near Thurii that Octavian’s father defeated Catiline’s militia, earning the cognomen Thurinum — a legacy that led young Gaius Octavius to be nicknamed Thurinus (Turinus).

These accusations of usury referenced real economic activities by his ancestors, particularly his grandfather. Suetonius (c. AD 69–122) described him as:

municipalibus magisteriis contentus abundante patrimonio tranquillissime senuit

Content with municipal offices, he lived richly and peacefully into old age

The family’s accumulated wealth enabled Augustus’ father, Gaius Octavius (100–59 BC), to merge their line with the patrician gens Iulia by marrying Atia Balba Caesonia (85–43 BC) in 70 BC. Atia, daughter of Atius Balbus of nearby Aricia (Ariccia) and niece of Julius Caesar, came from generations of senatorial nobility. She was related to both Caesar and Gnaeus Pompey Magnus—her mother was Caesar’s sister, Julia Minor. Octavian, therefore, was Caesar’s great-nephew. This marital strategy, common among ambitious municipal aristocracies, facilitated their social climb into the Senate.

Becoming a senator in ancient Rome meant joining the most powerful social group from the Republican era (6th–late 1st century BC). Senators accessed magistracies, political offices, and judicial-administrative roles. Consuls—Rome’s supreme leaders—were elected exclusively from their ranks. Though forbidden from direct commerce, senators amassed vast fortunes, later facing imperial-era restrictions favoring equestrians.

Octavian’s father, a businessman, was his family’s first senator. The Augustan writer Velleius Paterculus lauded him as a model magistrate and citizen — a homo novus (new man) whose brilliant career, Cicero noted, was cut short only by death. After governing Macedonia, he died suddenly in 59 BC at Nola en route to Rome, where he planned to run for consul. He perished in the same bedroom where his son Octavian would die decades later. His first wife, Ancharia, bore Octavia Major; his second, Atia Major, bore Octavia Minor and Octavian.

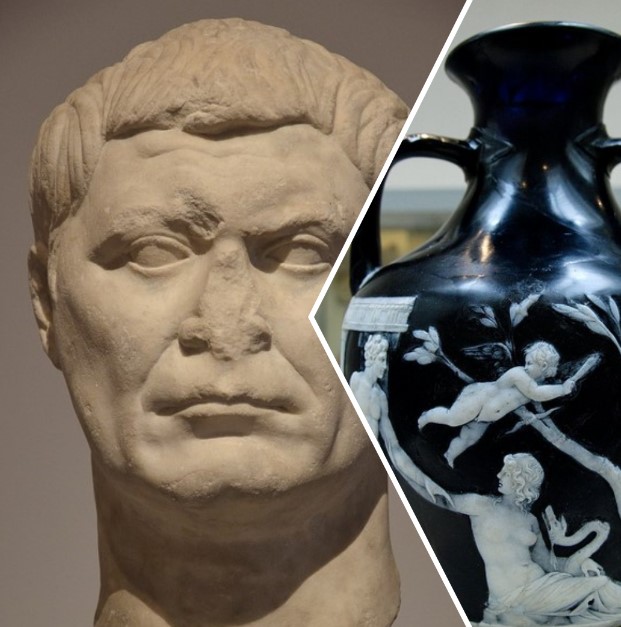

Head of Gaius Octavius, father of Octavian, sculpture (ca. 30-25 BC), found at San Giovanni Incarico (Frosinone, Italy), Paris - The Portland Vase, depicting Azia fertilized by Apollo in the form of a snake, British Museum, London

The Octavii became among the wealthiest and most influential families in Velletri’s ordo decurionum (local magistrates), owning a suburban villa there.

The Greek historian Cassius Dio (AD 155–235) claimed Augustus was born at Velitrae, his family’s ancestral home. Yet Suetonius, in The Lives of the Caesars, wrote he was born on Rome’s Palatine Hill but spent his youth in Velitrae with his paternal grandparents, where the family held significant property and influence:

Gentem Octaviam Velitris precipuam olim multa declarant

Many signs once declared the gens Octavia preeminent in Velletri

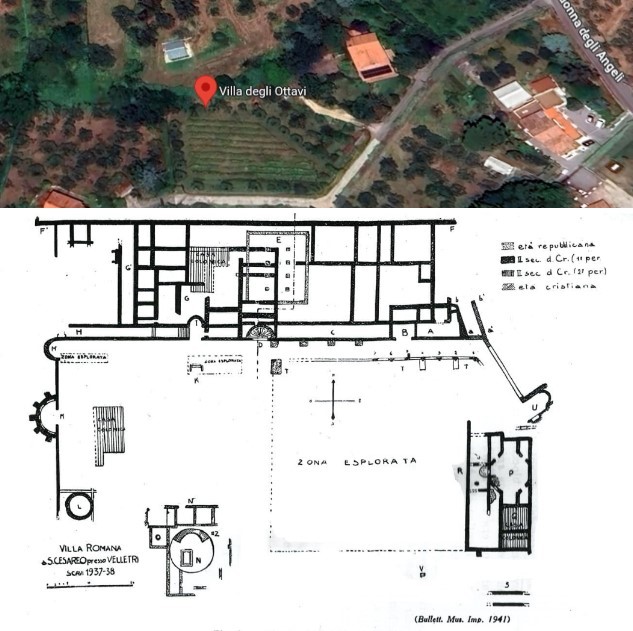

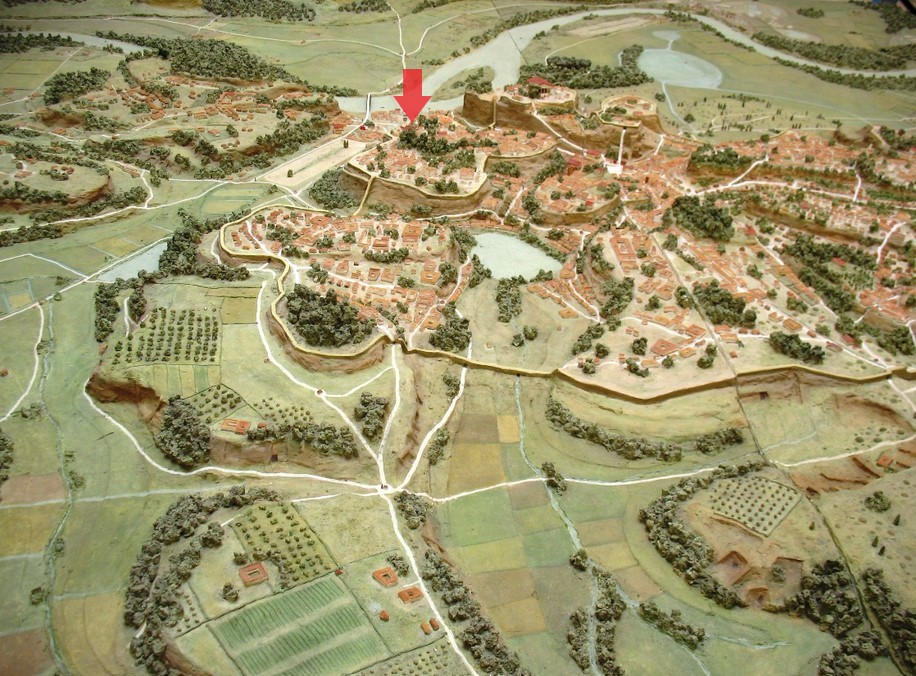

Suetonius placed the family’s residence in the city’s suburbs. Comparisons between Campana plaques from Velletri (late 1st century BC–early 1st century AD) and Palatine architectural fragments confirmed the villa’s identification — a rustic estate at the heart of a vast farm.

Campana plaques from Velletri (Madonna degli Angeli site): ‘Birth of Dionysus’ (late 1st century BC) and ‘Gorgon Medusa’ (Augustan era). Pellegrini Collection, Velletri Archaeological Museum.

Equivalent Medusa plaque from the Temple of Apollo on Rome’s Palatine Hill.

Campana plaques are decorated, painted terracotta slabs and simas (roof-edge gutters) used to clad public and private buildings from the mid-1st century BC. Named after 19th-century collector Marquis Giampietro Campana, his dispersed collection is now held in multiple museums.

Most villa remains are now inaccessible, having been absorbed into rural structures over centuries. However, excavations since the 1500s uncovered key artifacts (1st century BC–5th century AD): a marble head of Aphrodite (2nd century AD), coins (some bearing Augustus’ image), a two-faced Janus, a ship’s prow, a laureated head of Augustus, a bust of Hannibal, stamped roof tiles, a cistern, basins, a fountain, a nymphaeum, baths, and black-and-white mosaic floors.

Head of Aphrodite, mid-2nd century AD. Oreste Nardini Archaeological Museum, Velletri.

During the Republic, the villa was a modest domus. It expanded after Augustus’ victory at Actium (31 BC). Though he established his official residence with the Temple of Apollo on the Palatine, he likely retained this Velletri country estate. The property spanned ~100 acres (40 hectares), with the villa alone covering nearly 107,000 sq ft (10,000 m²). Linked to the Appian Way, it was structured on two terraces: the northern one for residential buildings, the southern for a viridarium (ornamental garden with fountains), a nymphaeum, and large baths.

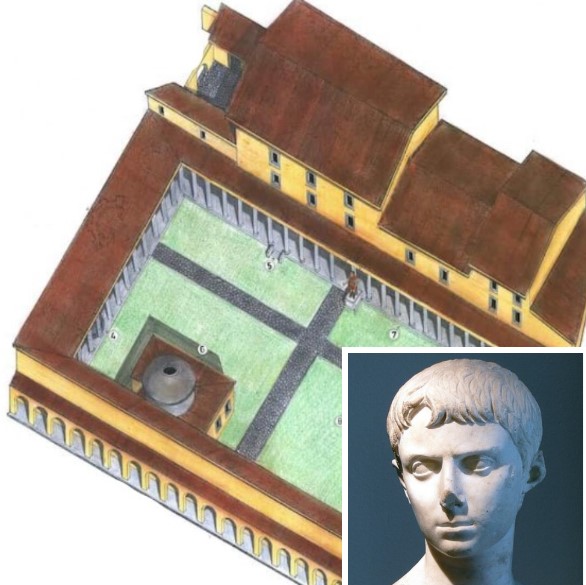

Villa of the Octavii at San Cesareo Hill, outside Velletri. Graphic reconstruction of the Villa. Aquileia Archaeological Museum.

Orphaned at four, young Gaius Octavius lived primarily with his paternal grandparents in Velitrae, avoiding Rome’s civil war between Caesar and Pompey (from 49 BC). His grandfather was a municipal magistrate; his grandmother was Julia Minor. At twelve, he delivered her laudatio funebris (funeral oration) before the assembled populace.

Graphic reconstruction of the Villa of Ottavi at San Cesareo - Archeological museum, Aquileia. Bust of Lucius Caesar ( 1st century BC ), inv. P. G. I.. See John Pollini (1987), The Portraiture of Gaius and Lucius Caesar. Fordham University Press.

So much for Antony's conduct. Now Gaius Octavius Caepias, as the son of Caesar's niece, Attia, was named, came from Velitrae in the Volscian country; after being bereft of his father Octavius he was brought up in the house of his mother and her husband, Lucius Philippus, but on attaining maturity lived with Caesar. 2 For Caesar, being childless and basing great hopes upon him, loved and cherished him, intending to leave him as successor to his name, authority, and sovereignty. He was influenced largely by Attia's emphatic declaration that the youth had been engendered by Apollo; for while sleeping once in his temple, she said, she thought she had intercourse with a serpent, and it was this that caused her at the end of the allotted time to bear a son.

- Dio Cassius, Histories, 45.1.1 - ca. 230 CE

After her first husband’s death, his mother Atia married her brother-in-law’s father, Lucius Marcius Philippus (consul 56 BC), who supported Octavian’s education. At sixteen, Octavian assumed the toga virilis.

He received military honors in Africa during his great-uncle Caesar’s triumph—despite being too young to fight. Caesar wanted him in the African campaign against Pompeians (47–46 BC), but Atia objected due to his youth and frail health. Yet Octavian soon joined Caesar in Spain against Pompey’s sons at Munda, braving enemy territory and shipwreck while still convalescing. His courage impressed Caesar, who later sent him to Apollonia in Epirus with his friend Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa to prepare for the Parthian campaign and study rhetoric under Apollodorus of Pergamon. There, Octavian learned of Caesar’s assassination (March 15, 44 BC)—and that he was named both heir and adopted son in Caesar’s will. Hesitant to summon Eastern legions, he returned to Rome to claim his inheritance.

Aged nineteen, Octavian arrived in the capital to assert his rights as Caesar’s son and heir, defying his mother’s doubts and his stepfather Philippus’ opposition. He shared the inheritance with Lucius Pinarius and Quintus Pedius (sons of Caesar’s other sister, Julia Major) but alone took Caesar’s name, becoming Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus. His political ascent began.

When his mother died in autumn 43 BC, the 20-year-old Octavian honored her with a lavish funeral.

View of the Palatine in the late Republican era

The Palatine: Rewriting Origins

Aged four, Octavian inherited his father’s home ad Capita Bubula ("at the Ox Heads") on Rome’s Palatine Hill. Little did he know he would refound the city itself.

Natus est Augustus M. Tullio Cicerone C. Antonio cons. VIIII. Kal. Octob. Paulo ante solis exortum, regione Palati ad Capita bubula ...

Augustus was born [...] in the Palatine district, at the Ox Heads.

- Suetonio, Life of Augustus,, V

The toponym, unique to Suetonius, may refer to marble bucrania (ox skull ornaments) or a pasture. Bucrania adorned Roman monuments and Greek sanctuaries, evoking sacrificial rituals. The term bubulum (relating to cattle) suggests the site was originally grazing land, possibly dating to Rome’s Regal period.

Bucranium on the Ara Pacis Augustae.

After leaving Velitrae, Octavian briefly lived near the Roman Forum above the Scalae Anulariae (Ringmakers’ Stairs) in orator Gaius Licinius Calvus’ former home.

Though no military genius, Octavian was among history’s most skilled politicians. Every alliance—friends like Agrippa, Maecenas, Virgil, and Horace; his indispensable wife Livia; his residences—was strategic. He chose the Palatine to tie himself to Rome’s mythical founders: Romulus’ hut, the Lupercal cave, and the mundus (foundation trench) were there. The hill also housed the aristocratic elite.

Fresco from the House of Augustus, Palatine Hill.

In 42 BC, as 22-year-old triumvir, he claimed the house of orator Quintus Hortensius Hortalus via proscriptions. He moved in after defeating Caesar’s assassins at Philippi. The choice was deliberate: by occupying Rome’s most prestigious hill, he signaled his ambition to surpass his uncle’s dictatorship.

The house was modest (29,750 sq ft / 2,764 m²), perched atop the Palatine near the Scalae Caci. Its tufa columns, lack of marble, and simple mosaics reflected restraint. For over forty years, Octavian slept in the same plainly furnished room, wintering there despite Rome’s harsh climate. When ill, he often stayed with Maecenas. His private study, nicknamed "Syracuse" or "the workshop," was upstairs.

House of Augustus, detail of the decoration of the private study

Around 36 BC, Octavian expanded his residence. Hortensius’ house no longer suited his status. He bought six adjacent properties—including Catiline’s former home—linking them to his wife Livia’s house. The new complex would become his imperial palace, austere yet worthy of the title Augustus ("revered one"), proposed in 27 BC by Munatius Plancus for its sacred connotations (auctus = bird flight omens).

Domus of Quintus Lutatius Catulus

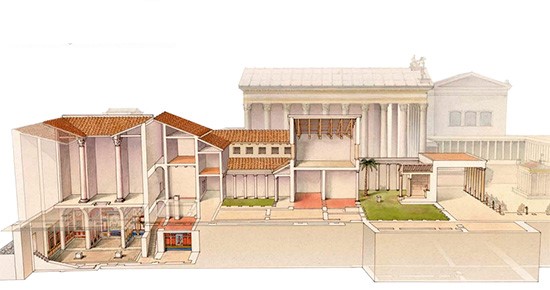

He first acquired the house of Quintus Lutatius Catulus, expanding to 92,200 sq ft (8,570 m²). Architects designed a palace with two courtyards, blending public and private spaces like Hellenistic royal courts. But plans shifted: the double-peristyle section was demolished and rebuilt higher, reflecting Octavian’s new emphasis on moral moderation.

During construction, a lightning strike in 36 BC was interpreted as Apollo demanding a grander dwelling. The house was buried as a foundation for a new structure triple its size (~236,800 sq ft / 22,000 m²). Funding came from Agrippa, whose naval victory at Naulochus that year secured Sicily and vast spoils. Velleius notes Octavian had vowed a Palatine temple to Apollo before the battle.

Agrippa’s wealth enabled further purchases, including properties once owned by Cicero and Clodius (father of Octavian’s first wife), confiscated after their owners backed Caesar’s assassins.

When fire later damaged his home, Suetonius records:

Veterans, decuriae, tribes, and citizens of all ranks donated money for its rebuilding. Augustus took no more than a single denarius from each.

Domus Augustana

Rome, Palatine hill