The Pharmacist’s Library Books That Vanished During the Two World Wars

Verona, Italy

Legnago, known as the birthplace of sacred, operatic, and classical composer Antonio Salieri, lies along the Adige River in the Veronese Plain. Extensive traces attest to its flourishing existence as early as the Bronze Age (13th century BC), followed by Etruscan settlement and finally Roman colonization. The Romans reclaimed and fertilized the countryside around Legnago, making it a reference point for Lower Verona for centuries.

Due to its position on the Adige—which becomes navigable only from this point onward—Legnago always held great strategic importance. Indeed, from the 10th century onward (when it settled into its current course), the river played a fundamental role in the city’s historical development.

In the 15th century, it was annexed by the Republic of Venice, which reinforced its fortifications, redesigning them in a star-shaped layout.Legnago, known as the birthplace of sacred, operatic, and classical composer Antonio Salieri, lies along the Adige River in the Veronese Plain. Extensive traces attest to its flourishing existence as early as the Bronze Age (13th century BC), followed by Etruscan settlement and finally Roman colonization. The Romans reclaimed and fertilized the countryside around Legnago, making it a reference point for Lower Verona for centuries.

Due to its position on the Adige—which becomes navigable only from this point onward—Legnago always held great strategic importance. Indeed, from the 10th century onward (when it settled into its current course), the river played a fundamental role in the city’s historical development.

In the 15th century, it was annexed by the Republic of Venice, which reinforced its fortifications, redesigning them in a star-shaped layout.

The 16th-century fortress of Legnago in an 1867 print and the remains of one of its towers

Legnago was first captured by the French in 1796, and in 1801, all fortifications were dismantled and demolished by order of Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821). At the time, the town was considered one of the Veneto’s most important river hubs due to its port on the Adige, a movable bridge designed for boat passage, and a long chain of mills. It was also a renowned cultural center with schools, a literary academy, and a theater. After Napoleon’s defeat, the town returned to Austrian control, and new fortifications were erected (1815).

Only with the annexation of Veneto to the Kingdom of Italy in 1866 did things appear to change, though many military encumbrances persisted until the late 19th century. To allow the town to expand beyond the fortress boundaries, the walls, bastions, and gates were entirely demolished, leaving only scant remains today.

In 1868 and 1882, two devastating floods of the Adige destroyed much of the urban center. Subsequent bombings during World War II destroyed most existing architectural works. Today, only a single Tower remains as a reminder of this mighty stronghold’s grandeur.

Legnago’s historic center in the 1800s, Via Roma.

In 1871, Legnago’s new elementary school was inaugurated, with Carlo Tegon appointed director. He revised the school schedule to run from 8 a.m. to 1 p.m., replacing the previous split schedule of three morning hours and two afternoon hours. This made schooling more accessible to students from rural areas. He also promoted girls’ education, challenging deep-rooted prejudices that persist in some rural areas today. He adjusted the academic calendar, adding about ten days of vacation during the harvest season when boys assisted their families in the fields.

It was no coincidence that Tegon, alongside teacher Carlo Marcati and Annibale Gallone, established the town’s first circulating public library to promote literacy.

In 1876, brothers Paolo and Girolamo Rocchetti fulfilled the wishes of their deceased brother Giuseppe—the pharmacist—by donating his library to support Legnago’s cultural life.

The 5,031 books were transferred to the local Gymnasium, merged with school texts, and formed the so-called Municipal Library. It became public in the modern sense only a century later.

Notably, the heirs’ 1876 donation letter to Legnago’s municipality emphasizes the donation’s purpose (fostering fellow citizens’ education) and their profound attachment to their hometown, hoping others would follow their example:

o the Honorable Mayor of the Municipality of Legnago

[...] we are most willing to comply with the wishes expressed by our late brother Giuseppe to bestow his books upon this Esteemed Municipality [...]

We hope our example will be followed by many others, so that this library may prosper and serve as a useful asset and credit to this respectable Town.

Here we add an observation: should misfortune later cause the Library to close, the donated books must remain with the Municipality as a perpetual memorial to the donor...

These brothers expressed a devotion to their town and a commitment to supporting culture for new generations—a sentiment also seen in soldier-writer-poet Giuseppe Cesare Abba (1838–1910)), who lived through those decades of political upheaval leading to Italy’s unification.

In the early 20th century, the circulating public library was dissolved. Concurrently, the municipal library—long the school library of a gymnasium—developed, with Giuseppe Rocchetti’s book donation as its core.

But the Rocchetti bequest was mismanaged and squandered, as happened with other private donations like musician Alfonso De Stefani’s library. Key causes included WWI events in the town (1915–1918), starting with vandalism by Italian soldiers billeted in Legnago’s elementary school (soldiers reportedly burned books for warmth). The 1945 bombing of the Town Hall and schools delivered the final blow: nearly 3,700 books were lost over a century.

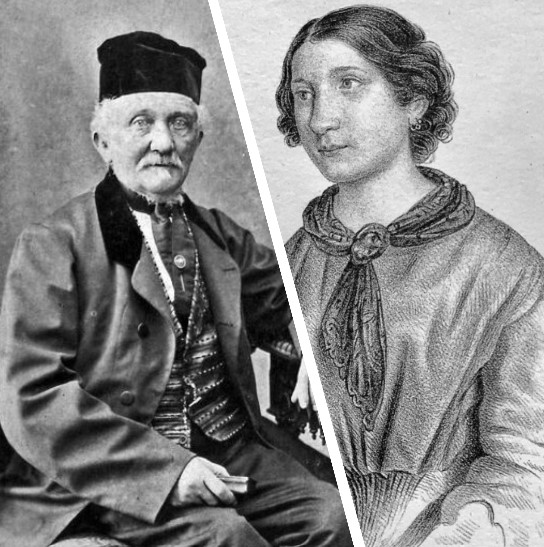

Giuseppe Rocchetti (1799-1874) and his wife Amalia Kiriaki (1803-1854)

Giuseppe Rocchetti (1799–1874) was born in Legnago when Napoleon’s army still occupied it but lived most of his life under Austrian rule.

We have fragmentary information: young Rocchetti completed elementary and secondary school around age 15 (1814); mastered Latin, Greek, French, and German; fulfilled mandatory pharmaceutical training; enrolled in a two-year university course; and qualified as a pharmacist in 1820 at the University of Padua.

Legnago and Porto, Via della Stazione in 1909

Professional licensure required a five-year apprenticeship "under a licensed pharmacist." Records show the 25-year-old was an assistant at De Steffani’s pharmacy in 1824, residing in neighboring Porto, a hamlet on the river’s left bank.

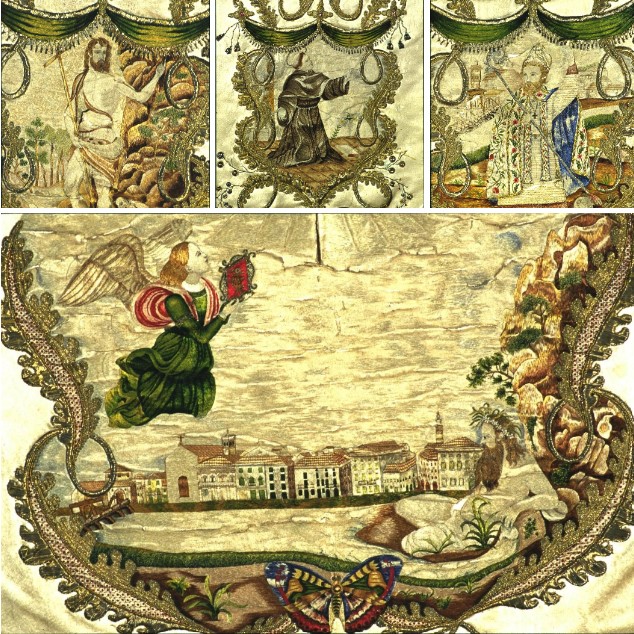

The following year, he married young Triestine governess Amalia Rosa Ciriachi (1803–1854). A cultured, deeply religious woman, she engaged in educational, philanthropic, and charitable work, leaving a lasting legacy in 19th-century Legnago. She served on the town council, taught at her private girls’ school in artistic embroidery (a local pride), and embroidered the cope and humeral veil for St. Martin’s Parish—now displayed in the Cathedral Oratory’s case.

The cope and humeral veil of St. Martin’s Parish embroidered by Amalia Rosa Ciriachi, now preserved in a display case in the Cathedral Oratory

In 1826, the newlywed opened his own pharmacy, "La Salute" (Health), on Via Passeggio, near the future family home.

Despite his primary work in chemistry-pharmaceutics, he devoted himself to botany and territorial studies using agronomic knowledge. As a member of Verona’s Academy of Agriculture, Sciences, and Letters (from 1848), he conducted meteorological observations. He botanized in the Veronese area, discovering Aldrovanda vesiculosa—a rare, endangered rootless aquatic carnivorous plant native to Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia that traps invertebrates—in the moats of Legnago’s fortress.

In 1876, his heirs donated his valuable mineral collection and extensive herbarium (assembled through years of fieldwork near the Adige town) to the Academy.

Aldrovanda vesiculosa

The scientist practiced pharmacy lifelong in the small Adige town of Legnago alongside his pharmacist brother Girolamo.

Pharmacies were then called “spezierie”: establishments for preparing, storing, and dispensing medicines, managed by an “speziale” (apothecary).

Pharmacies featured tall shelves displaying ceramic jars from Pesaro, Siena, and Florence. Later, Bohemian crystal bottles appeared. A massive solid-wood counter dominated the entrance, often showcasing artistic scales. Niches held statues of Hygeia and Aesculapius. Laboratories were cluttered with alembics, mortars (some magnificent bronze ones), and cauldrons.

In those times, pharmacies were social hubs—not just prescription dispensaries but meeting places akin to cafés, frequented by mayors, doctors, literati, politicians, intellectuals, and villagers. Via Passeggio’s pharmacy was also a privileged gathering spot for local landowners seeking novelty, debate, and knowledge exchange, set against a rigidly traditional rural backdrop dominated by wheat, corn, and rice—plus vineyards and sparse industrial crops like castor oil and flax.

Interior of a Victorian-era pharmacy (1897)

Rocchetti clearly came from a wealthy family, as he and his siblings attended university.

His brother Paolo Rocchetti, a renowned engineer and mechanic at Padua University’s astronomical observatory, lived in Padova. He also ran a foundry and precision workshop, producing geodetic instruments, tower clocks, astronomical pendulums, chronometers, tachymeters, hydrometers, pumps, and physical/orthopedic machines.

When Giuseppe Rocchetti died, Paolo was temporarily in Padua. Eight years later, brother Girolamo (nearly 70) also moved there.

Fondazione Fioroni Museum, Legnago

We know the pharmacist’s 5,000+ books—including dozens of incunabula, 16th- and 17th-century editions, and 180+ texts deemed "valuable"—ended up at the Fioroni Museum in the decades before WWII. Their traces were quickly lost. Later, it was discovered that in 1969, a cache of old books was donated to a small library at a state secondary school in Legnago, where they lay unused and unusable for years, their content and origin unrecognized.

In 2007, the volumes were moved to rooms in Legnago’s town hall, where it was revealed that this indistinct mass contained over one-fifth of the Rocchetti library, fragments from other Legnago libraries (including part of the circulating library), and likely texts from pre-WWII gymnasium-high school and technical institute libraries.

Though some volumes from the vanished Rocchetti library were recovered, many shadows obscured what truly happened after the 1876 donation—particularly how and why this vital collection disintegrated, was abandoned, or possibly even stolen between 1944 and 1945. Indeed, nearly 200 antique volumes vanished despite being cataloged and, in some cases, stored in a local bank’s safe deposit boxes to protect their high market value.

Today, fragments of the Rocchetti library are deposited and cataloged in the Antique Collection of Legnago Municipality at the Fondazione Fioroni.

Via Giacomo Matteotti, 43, Legnago (Verona)