Abba Giuseppe Cesare, the soldier poet teacher

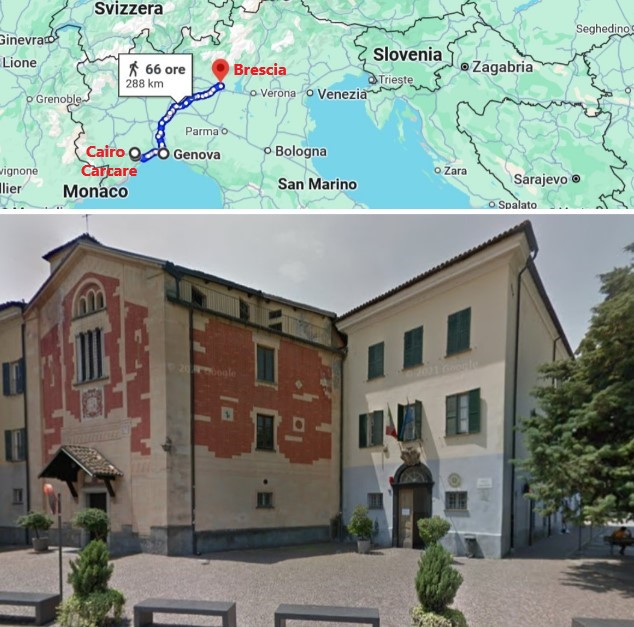

Brescia, Italy

Walking along one of the avenues leading to the entrance of Brescia Castle in Lombardy, you encounter a plaque dedicated to Giuseppe Cesare Abba (1838–1910). This work by Giuseppe Brigoni was unveiled on September 20, 1926. It bears a bipartite inscription: the first phrase alludes to Le Alpi nostre (Our Alps), a reading book this "soldier-poet-teacher" wrote for upper elementary schools; the second proclaims, in the face of the disappointment of the "mutilated victory," the undying claims to Italy’s unredeemed lands. Completing the epigraph is a bronze bas-relief of Abba’s bust, his right forearm resting on a closed tome, an open book before him, and two scenes from the Expedition of the Thousand in the background—iconographically representing the patriot who taught "by example" through his Garibaldian past and "by word" as a writer and educator.

Monument to Giuseppe Cesare Abba in Brescia. 'TO GIUSEPPE ABBA, SOLDIER POET TEACHER, WHO WITH HIS EXAMPLE AND WORDS POINTED OUR YOUTH TO OUR ALPS. THE ENLIGHTENED BRESCIAN GENERATION, BY THE LIGHT OF HIS FAITH, CLAIMS THE SACRED BORDERS', and Brescia's Castle

Giuseppe Cesare Abba was born in Cairo Montenotte, Savona, Liguria, on October 6, 1838, to Giuseppe and Gigliosa Perla. The family’s original surname was Abbate, which became Abbà with his grandfather Francesco and then Abba with his father; though in some letters addressed to him in his youth, he was still called Abbà.

Cairo Montenotte, Savona, Liguria

Cairo Montenotte is a small town inland from Savona in Liguria. Since Roman times, it has been a vital link between Piedmont and Liguria’s ports, largely due to the via Emilia Scauri and later the Magistra Langorum.

From the Middle Ages, Cairo has been a key location in the Langhe—a hilly territory in the heart of Piedmont whose name derives from the Piedmontese dialect langa (meaning "hill"). Today, the Langhe are a UNESCO World Heritage site, recognized as "an exceptional living testimony to the historical tradition of vine cultivation, winemaking processes, and a social, rural, and economic fabric based on wine culture."

In the 19th century, Cairo flourished industrially as part of Italy’s "Industrial Triangle." It was simply named Cairo until 1863, when "Montenotte" was added in honor of the Napoleonic Battle (1796) fought in its namesake hamlet.

Depicts the Battle of Castiglione ordered by Louis-Philippe for the museum in 1836

As a boy, Abba lived—like all children of his time—with little formal schooling until age eight or nine. From eleven to sixteen, he studied at the Scolopi (Piarist) boys’ college in nearby Carcare. The Scolopi, a pontifical religious institute founded in the 16th century, trace their origins to free popular schools dedicated to the Christian education of youth, especially the poor.

On the right, adjacent to the church, the former Piarist Fathers' (also known as Scolopi) monastic school at 3 Piazza Calasanzio, Carcare (SV)

At this college, the fervor of 1848 (a pivotal year for Italy, marked by revolutionary uprisings, wars, and independence efforts against Austrian rule) remained vivid. Several priests ignited the minds and hearts of their students, instilling a love for literature, art, and the fatherland. After completing his studies, Abba enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Genoa but soon abandoned it.

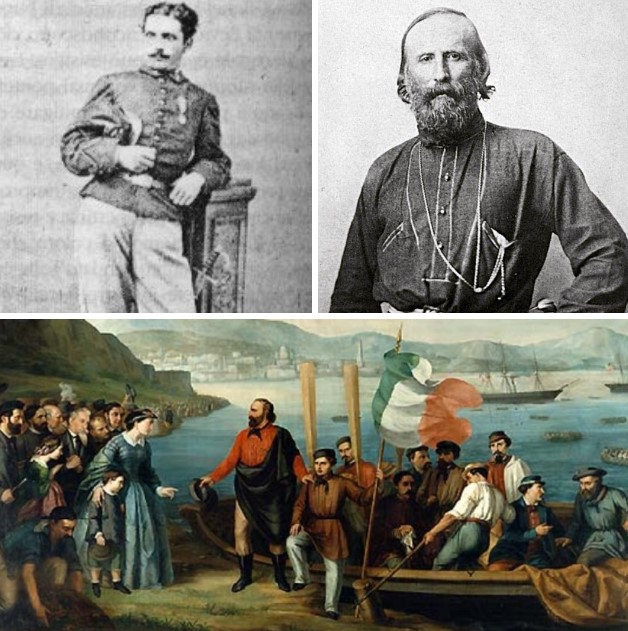

Giuseppe Cesare Abba on year 1861 and Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882)

Too old for high school and uncertain of his path—yet craving action—Abba enlisted as a volunteer in the cavalleggeri d'Aosta (cavalrymen) at age 21. At the time, the Kingdom of Sardinia was allied with Napoleon III’s France against Austria, and the Cavalleggeri d’Aosta helped defeat Austrian forces. The young Abba hoped this military experience would define his future, but it brought only bitter disillusionment and inactivity.

Discharged in October 1859, six months later he joined Garibaldi’s heroic venture in Parma—a defining moment that illuminated his life. Among the Thousand volunteers, he found three former classmates from Carcare. The Expedition of the Thousand, led by Giuseppe Garibaldi, proved decisive for Italian unification: it conquered the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, paving the way for annexation to Sardinia and the 1861 proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy.

Abba joined as a private soldier, rising to quartermaster sergeant and finally second lieutenant. He fought heroically, earning an honorable mention. Day by day, he recorded events in a notebook, publishing them only 70 years later.

After Garibaldi’s army disbanded, Abba returned to Cairo before enrolling at the University of Pisa. There, he rejoined young friends—former comrades-in-arms turned students—attending lectures by great professors who had fought in Italy’s struggles. These were vibrant years for youths dreaming of a unified nation.

During preparations for the Aspromonte campaign (1862), Abba left for Turin and Genoa but was detained by authorities and barred from reaching Garibaldi. He resumed his studies in Pisa, immersing himself in history and literature. He began writing: the poems In morte di Francesco Nullo (On the death of Francis Nullo, 1863) and Arrigo. Da Quarto al Volturno (Arrigo, from Quarto to Volturno, 1866).

In 1866, action called again. Leaving Pisa’s tranquility, Abba rejoined Garibaldi’s forces, earning a silver medal for military valor "for following the flag with a few brave men and saving two artillery pieces."

Forced back to Pisa by events Garibaldi could not prevent, Abba fell seriously ill. He returned to Cairo, where he remained for over a decade (1867–1880). These were years of solitude for the thirty-year-old Abba, yet he devoted himself to his town: promoting education, hygiene, and civic life. In rural Italy then, peasant children attended infant asylums only until "their tender age made them fit for labor." By six, many worked alongside parents—schooling was deemed useless in the countryside. In industrial cities, children from poor families (some as young as five) labored 13–15 hours in unsafe factories for one-third of an adult’s wage, often under corporal punishment.

Filippo Carcano, 'Workers at Rest' (1886; oil on canvas; Private Collection)

Abba believed that if all who witnessed Italy’s revolutionary deeds devoted their minds and labor to their birthplaces—however small—the greater fatherland would swiftly recover lost time. Serving the "greater homeland," he tackled local issues as councilman and later nine-term mayor of Cairo: improving elementary education, funding farmers, establishing workers’ mutual aid societies, developing public infrastructure, and introducing modern farming. He also ran twice (unsuccessfully) for parliament.

Amid daily duties, Abba never abandoned letters. Gradually, his literary work merged with heroic memories of his youth. He wrote the Manzoni-inspired novel Le rive della Bormida nel 1794, (The Banks of the Bormida in 1794), recounting stories of his valley during the 1794 French invasion as told by elders. He also published Noterelle d'uno dei Mille edite dopo venti anni (Notes by One of the Thousand after twenty years), later expanded as Da Quarto al Volturno. Noterelle d'uno dei Mille (From Quarto to the Volturno: Notes by One of the Thousand).

His work won broad acclaim, including praise from poet-critic Giosuè Carducci, who became a friend. With Carducci’s support, Abba was appointed an Italian professor at secondary schools. At 43, he began teaching, eventually settling permanently in Brescia.

In his final years, he wrote popular works on Garibaldi’s history (Storia dei Mille narrata ai giovinetti, 1904; Cose garibaldine, 1907) and textbooks for schools and the army. His last poetry collections were Dogali (1887) and Vecchi versi (Old Verses, 1906).

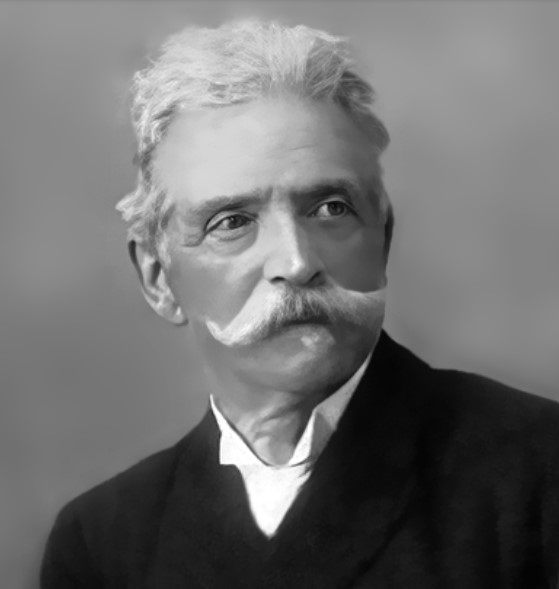

An old Giuseppe Cesare Abba

At 72, near life’s end, Abba traveled to Sicily for the 50th anniversary of the Thousand’s landing, retracing places he had immortalized in his memoirs. In June 1910—after attempting to decline—he was appointed senator "for services rendered to the fatherland." That November, he died suddenly on Via del Castello in Brescia, where a plaque now honors him.

Giuseppe Cesare Abba lived humbly, without pretense, ambition, or wealth. His vivid, detailed writing awakened generations of readers, capturing the atmosphere and emotions of his historical moment. As a firsthand participant, he chronicled pivotal events, volunteers’ passions, hardships, and hopes during the journey toward Italian unification.

Via del Castello (Brescia)