Hadrian’s Mausoleum

Rome, Italy

Publius Aelius Traianus Hadrianus was a Roman Emperor who reigned from 117 to 138 AD. In imperial propaganda, he explicitly invoked the first Emperor Augustus, positioning himself, like his predecessor, as a peacemaker and restorer of Rome's greatness. He was the third of the "Adoptive Emperors," and his policy focused on consolidating the empire's frontiers rather than expanding them. A formidable emperor and staunch opponent of Judaism, he nonetheless adopted a more tolerant stance towards Christians, though he did not embrace their doctrine.

Hadrian was of Spanish origin, a refined spirit educated in Greek letters and a passionate lover of Hellenism. He possessed a nostalgic soul, forever seeking beauty throughout every corner of the empire. Wherever he journeyed – in Asia or Africa, Gaul or Illyria – he left traces of his passage. It can truly be said that he was the great popularizer of Roman civilization, arriving after the conquerors. Lands that once held only humble thatched huts became enriched with architectural monuments, testaments to Latin grandeur and the dawn of a new civilization. No emperor, no sovereign before or since, surpassed Hadrian in munificence for erecting new buildings and restoring ancient ones. An architect himself – and not an unskilled one, judging by the Temple of Venus and Roma – he yearned to see his dreams rendered in stone and marble.

The defining characteristic of his monuments was an extreme elegance combined with the scenographic grandeur that had become the fundamental basis of Roman art. Hadrian loved the splendor of great edifices and the sumptuous appearance of decorative artworks. Moreover, as a capable ruler and zealous guardian of imperial dignity, he felt compelled to enrich Rome with buildings that would glorify his name. By his death in 138 AD, the city had achieved a brilliance that subsequent emperors would further enhance, though without drastically altering the metropolis's overall form.

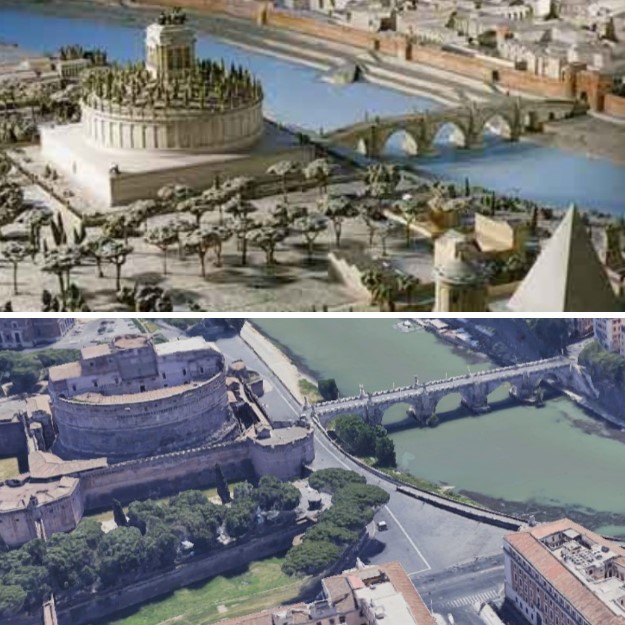

Castel Sant'Angelo and the Model of Hadrian's Mausoleum

Nearly two thousand years have passed since the construction of the funerary mausoleum commissioned by Emperor Publius Aelius Traianus Hadrianus for himself and his family on the right bank of the Tiber. This tomb (known today as Castel Sant'Angelo) was imposing. It featured an earthen mound atop either a cylindrical structure or a circular tholos, surmounted by a building that likely housed a small temple crowned by a bronze Quadriga of the Sun, driven by the Emperor Hadrian depicted as Sol Invictus.

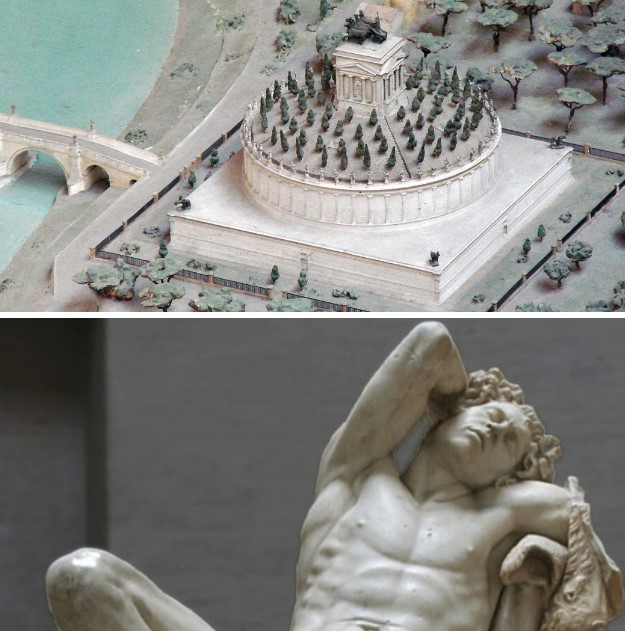

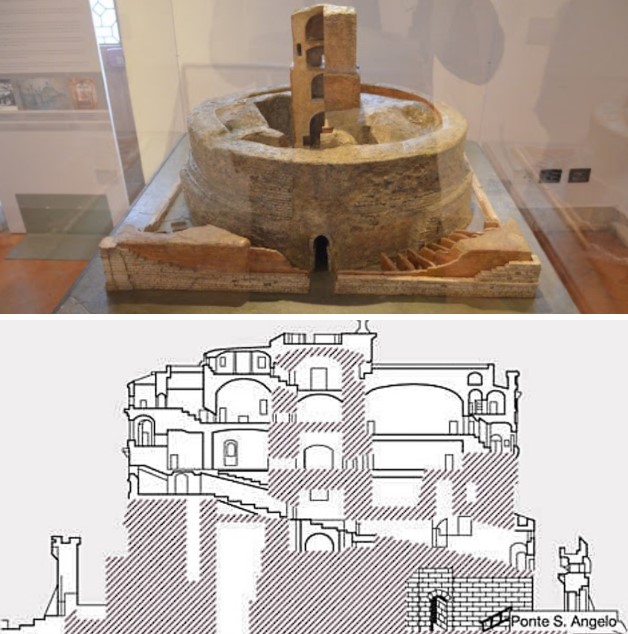

Model of Hadrian's Mausoleum: Showing the base, the circular structure, the mound, and the small temple topped by the Quadriga of the Sun.

Hadrian's Mausoleum was astronomically aligned to create special light phenomena around the Summer Solstice (June 21st). The Sun, an ancient symbol of divinity, royalty, and power originating in Mesopotamia and spreading through Egypt, Greece, and Rome, played a key role. The deified Emperor Hadrian, identified with the Sun, sent a 'luminous signal' by illuminating his own sarcophagus twice on that day. Complex and significant ritual ceremonies associated with the cult of the dead and the emperor's own apotheosis took place then: a procession would wind up the long helical ramp, reaching the Hall of Urns and the temple atop the Mausoleum itself.

Section of the Mausoleum: Showing the Hall of Urns and the two Courtyards where 'wolf's mouth' windows allowed beams of light to pass during the Summer Solstice.

The massive structure was positioned opposite the Campus Martius, connected to it by a bridge (Pons Aelius, now Ponte Sant'Angelo) completed before work on the Mausoleum began. In the imperial plan, the bridge and Mausoleum were conceived as a single unified structure. Located on undeveloped, marshy imperial land, the Mausoleum was enormous and easily distinguishable from much of the city. Originally, it stood an impressive 47.52 meters tall (excluding the quadriga on top), a height deduced from surviving Roman traces reaching the level of the Angel Terrace.

Today, Castel Sant'Angelo sits in a central Roman neighborhood, but when the emperor chose this site, it was a distant periphery, home to roadside tombs, gardens, villas of noble families and emperors, circus games, and important exotic cults.

Location of Hadrian's Mausoleum (left) and Augustus's Mausoleum (right). Below: Model of Octavian's Mausoleum.

Together with the other great Roman mausoleum, that of Augustus, it formed a landmark for those approaching the city from the north. The desire to surpass the Augustan mausoleum in grandeur was a clear signal of power the emperor wished to communicate, alongside the cult of the emperor and the imperial family. The two funerary monuments stood less than a kilometer apart, intended as tangible symbols of their patrons' acquired power. The Mausoleum was an assertion of personal power and the emperor's stature. In Ancient Rome, power was often expressed through death and its celebration. Tellingly, their scale exceeded Rome's most ambitious tombs and echoed the renowned examples of the Hellenistic age, where the cult of the emperor originated in the Western world.

Graphic Reconstruction of Hadrian's Mausoleum.Graphic Reconstruction of Hadrian's Mausoleum.

Hadrian probably conceived the mausoleum as the dynastic tomb for his family, replacing the Mausoleum of Augustus which had served that purpose until then. While he sought to preserve ancient tradition and essentially followed the main lines of Augustus's mausoleum (itself resembling circular tombs like the Tomb of Caecilia Metella on the Appian Way or the Mausoleum of the Plautii in Tivoli), his ambition may also have been to rival the splendor of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (the tomb of Mausolus of Caria), one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Its construction was likely entrusted to the architect Demetrianus, beginning around 130 AD. It took nine years, completed one year after the emperor's death by Antoninus Pius. Besides Emperor Hadrian and his wife Vibia Sabina, the mausoleum housed the remains of Emperor Antoninus Pius and his wife Faustina the Elder, three of their children, Lucius Aelius Caesar, Commodus, Emperor Marcus Aurelius and three of his sons, Emperor Septimius Severus, his wife Julia Domna, and their sons and emperors Geta and Caracalla.

Detail of the Mausoleum's podium in tufa blocks.Detail of the Mausoleum's podium in tufa blocks.

To protect the mausoleum from Tiber floods, it was built on an enormous, exceptionally robust quadrangular base. Made of large tufa blocks in opus quadratum, measuring about 86,3 meters per side, it was reinforced internally by a system of radial walls alternating with empty chambers. It was clad in Luna marble slabs, adorned with Corinthian pilasters, and enriched at the top by a decorative frieze of ox skulls (bucrania) with garlands. The frieze facing the river bore the names of the emperors buried within.

One of the marble friezes decorated with garlands and bucrania at the National Roman Museum.

On this base rested a cylindrical structure (64 m diameter), also built in tufa and opus caementicium and once entirely clad in travertine blocks (some remain). The structure was crowned at the four corners by sculptural groups depicting men and horses, as recorded by Procopius of Caesarea (a physician accompanying Belisarius during the Greco-Gothic wars of the 6th century). Numerous decorative statues, marble columns, and precious vases adorned the colossal exterior. Surrounding the mausoleum was a perimeter wall with a bronze grille (about 116 meters per side), decorated with gilded bronze peacocks (2nd century AD).

Gilded bronze peacocks from Hadrian's Mausoleum, Vatican Museums, Chiaramonti Museum.

Technologically, each peacock was originally composed of 7 separately cast elements joined together later. After the fall of Rome and the mausoleum's transformation into a fortress, only two peacocks were recovered. They were reused to decorate the Pigna Fountain (the Cantharus, for pilgrims' ablutions) in the quadriportico of the first St. Peter's Basilica. The other peacocks were looted, stripped, or destroyed as symbolic works of Roman citizenship. When the basilica was rebuilt in the 16th century, the pinecone and the two peacocks were moved to one of the Belvedere courtyards. Inside the Cortile della Pigna of the Vatican Museums, flanking the fountain, copies of the two peacocks in non-gilded bronze have been placed symmetrically since 1704, while the originals were moved inside the Braccio Nuovo for conservation. In Roman times, peacocks, associated with Juno, symbolized royalty. In the Christian era, they became associated with Christ, symbolizing immortality and resurrection – reflecting the bird's annual shedding and regrowth of feathers.

Model of Hadrian's Mausoleum and the Barberini Faun, copy of a bronze original, 220 BC, Archaeological Museum, Munich.

Above the square base rose a drum made of peperino and Roman concrete (opus caementicium), completely clad in travertine and fluted pilasters. Above this stood an earthen mound planted with trees, surrounded by marble statues adorning the monument's perimeter; fragments of these statues have been found on site. The most intact statue recovered is the famous Barberini Faun.

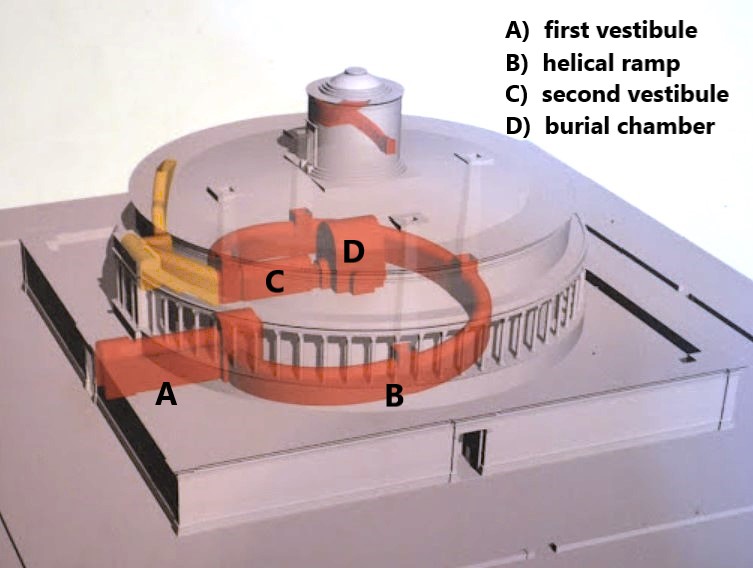

Axonometric view highlighting the internal Roman-era passages of Hadrian's Mausoleum (in red: dromos, Roman atrium, helical ramp, second vestibule, Hall of Urns, and access to the monument's summit).

To access the mausoleum, the emperor built the Pons Aelius (Aelian Bridge, now Ponte Sant'Angelo), which faced its entrance, linking it to the Campus Martius. It was a truly triumphal approach, an aesthetic complement worthy of the mausoleum. Originally composed of eight large travertine arches and decorated with statues on its parapets, it is the only imperial bridge to survive to this day, though completely transformed by Baroque renovations. Reduced to five arches during riverbank works and with its lateral arches diminished, its decorations underwent many changes. However, throughout the Middle Ages, the Pons Aelius remained the bridge par excellence and the only direct access between the city and St. Peter's Basilica. During the Lungotevere works in the 1930s, some original arches were identified and, shockingly, destroyed.

First Entrance Vestibule, with holes for marble clamps visible on the walls.

Crossing the bridge, one reached the arch dedicated to Hadrian, leading into a majestic rectangular vestibule (the dromos), still existing today, built in travertine blocks and once entirely clad in giallo antico marble. Sadly, the entrance portal, originally four or five meters below the current level, is no longer visible due to demolition works in the 14th and 15th centuries. However, part of the dromos (the corridor leading to the first vestibule) is preserved. In an enormous niche within the vestibule stood a colossal statue of Hadrian. Only the head remains, now on display in the Vatican Museums.

Colossal Head of Emperor Hadrian, Vatican Museums, Pio-Clementine Museum, Vatican City.

At the far end of the vestibule opens the entrance to a helical ramp made of brick, originally marble-clad, spiraling within the cylindrical structure. This gently ascending ramp connected the entrance or dromos to the burial chamber at the center of the mound. Illuminated by light wells, the ramp makes a full 360° turn, rising in height, and terminates at a second vestibule situated exactly above the first, but twelve meters higher.

Helical ramp ascending inside the Mausoleum to the second Vestibule.

In Roman times, upon entering the second vestibule, the path forked, offering two different routes:

• The first led to the small temple atop the Mausoleum via a now-vanished staircase. This route has been almost completely obliterated by Renaissance transformations. An explosion largely destroyed the temple, and the remnants were transformed into a room.

• The second led to the burial chamber (Hall of Urns) where the emperor's sarcophagus lay; this chamber is perfectly preserved, though completely altered. From the door, one descended a corridor paved in black-and-white mosaics to the funerary cell: a square room with walls and vault of peperino, where the porphyry sarcophagus containing the ashes of Hadrian and Sabina lay in the center.

The sarcophagus remained at the Mausoleum until the structure was dedicated to the Archangel Michael under Pope Boniface IV (608 – 615 AD). This occurred because under Pope Gregory I (540-604 AD), Rome was ravaged by a severe plague. Gregory organized a solemn penitential procession.

Jacopo Zucchi, The Procession of St. Gregory (1573-1575), oil on wood panel, Vatican Pinacoteca, Rome - Depicting St. Michael the Archangel statue on Castel Sant'Angelo.

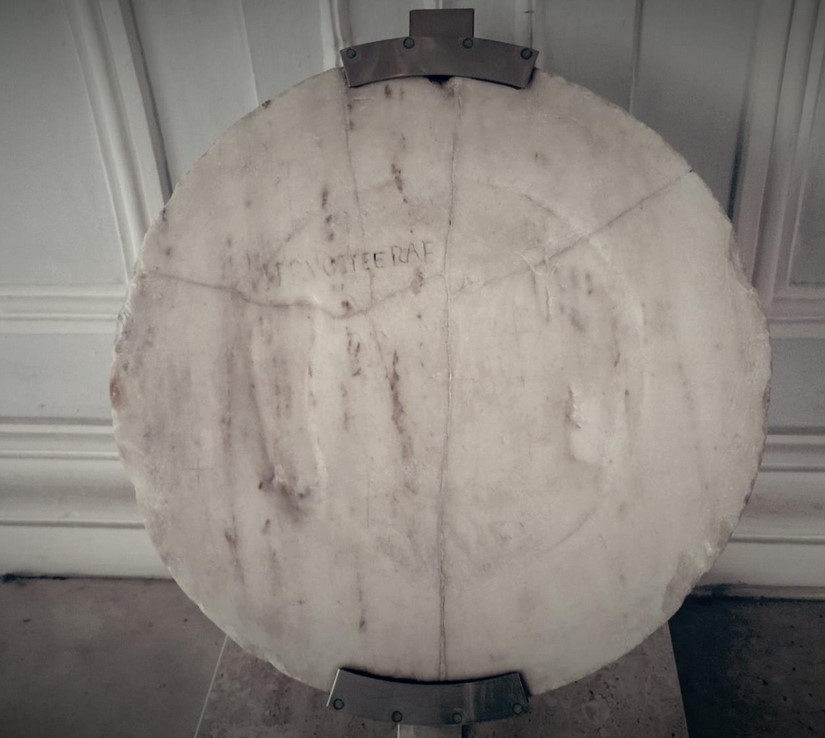

As the Pope, leading the procession, crossed the Pons Aelius, he had a vision of the Archangel Michael atop Hadrian's Mole sheathing his sword. This was interpreted as a heavenly sign heralding the imminent end of the epidemic, which indeed occurred. From that moment, Hadrian's Mole became known as Castel Sant'Angelo (Castle of the Holy Angel), and a church dedicated to "Sant'Angelo usque ad caelos" (St. Angel to the Heavens) was erected on its summit. A circular stone bearing footprints, traditionally believed to be those left by the Archangel when he stopped to announce the end of the plague, is still preserved in the Capitoline Museums.

Circular stone with footprints of Archangel Michael (ex-voto), Rome, Capitoline Museums.

Consequently, the sarcophagus was dismantled. The lower tomb section was transported to the Lateran Square, while the lid was first used as the tomb of Emperor Otto II and later ended up under the porticoes of the old St. Peter's Basilica. In 1698, the sculptor Carlo Fontana transformed it into a baptismal font still in use in the current St. Peter's Basilica. The lower part of the sarcophagus was then used as the tomb for Pope Innocent II (1130 – 1143), but both the sarcophagus and the Pope's body were destroyed in a partial collapse of the old basilica caused by fire.

The red porphyry lid of Emperor Hadrian's sarcophagus, transformed into a baptismal font. Now conserved in St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican City.

The funerary building began to decline starting in 403 AD when Emperor Honorius incorporated it as a stronghold reinforcing the Aurelian Walls. From that moment, the building lost its original sepulchral function and was consistently referred to as a fortress or castellum, saving the Vatican area from numerous barbarian incursions (like the Visigoths under Alaric in 410 and the Vandals under Genseric in 455). During these sieges, the defenders reportedly threw down anything at hand, even statues – one of which, the so-called Barberini Faun, was later found in the fortress ditches.

The Mausoleum lost its original form, was surrounded by bastions and fortifications, and overburdened with lodgings for refugees. By the early 6th century, Theodoric used it as a state prison. In the 8th and 9th centuries, it was called Adrianum; part of the square was formerly called 'via delle Fosse' (Street of the Ditches) after the moats that still surround the monument, framing the gardens. In the 13th century, a statue depicting the Archangel Michael sheathing his sword was placed atop the castle.

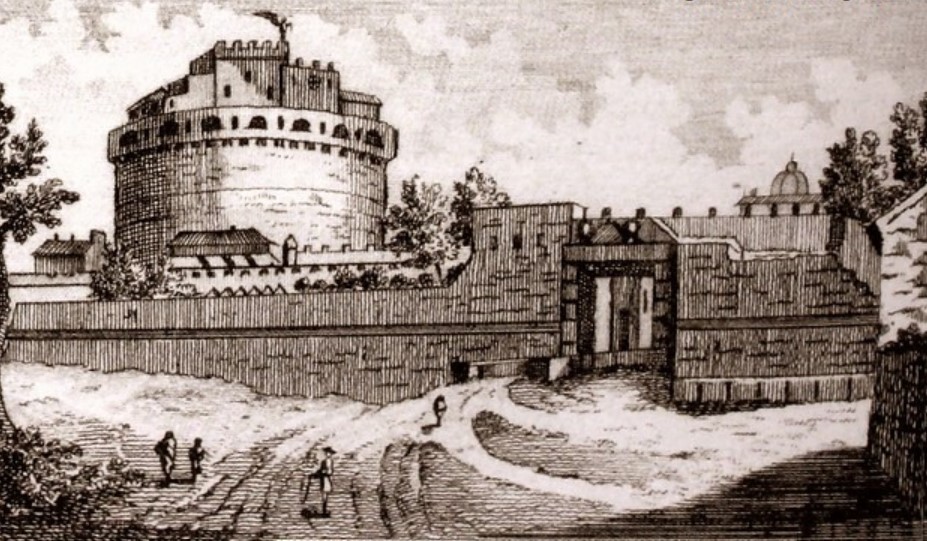

Castel S. Angelo depicted by G. Vasi, c. 1747.

During the Renaissance, the mausoleum was transformed into the present Castel Sant'Angelo, encasing it in brick curtain walls, adding battlements, and creating new rooms on the summit. Remarkably, it's estimated that about 70-80% of the Roman structures survive within this modern shell.

Model showing the remains of the Roman walls pertaining to Hadrian's Mausoleum (the shell).

The gardens opened to the public in 1938 are collectively called Parco Adriano (Hadrian's Park); well-maintained, they cover 1,250 square meters.

Rome, Lungotevere Castello, 50