Priscilla, The Queen of the Catacombs

Rome, Italy

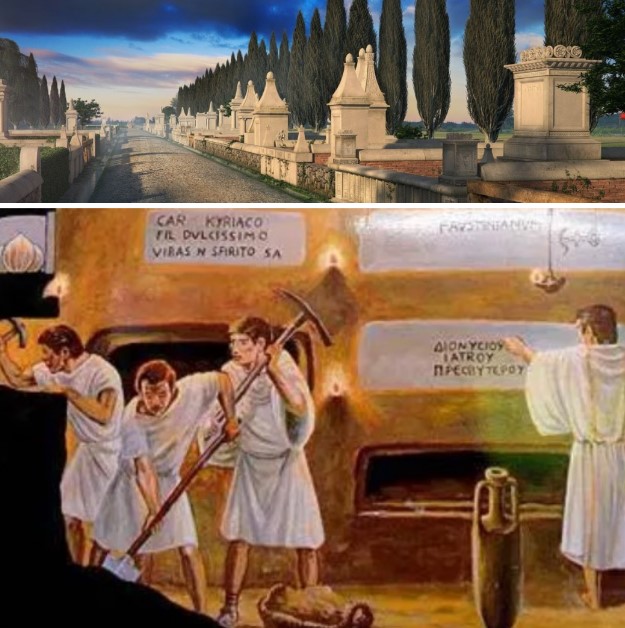

In the ancient days of Rome, the pagans laid their beloved to rest along the consular roads, within tombs built beyond the city walls—for many reasons. These sacred grounds were easily reached, offered ample space, and, most importantly, rested under the watchful eyes of the infernal gods, while the city itself remained guarded by the solar deities.

The Christians, too, buried their dead in similar fashion, yet with one solemn difference: their loved ones could not be cremated, for fire would consume the body and deny it the promise of resurrection. The earliest Christian cemeteries still lay beneath the open sky, emerging between the 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D., as many wealthy converts—families like the Flavii and the Acilii—opened their private burial grounds to others, honoring the Christian creed of equality.

But as the decades passed, the free spaces along the consular roads dwindled, and the Christians, ever resourceful, turned their gaze downward. Beneath the earth, they carved out their resting places—and so, from necessity and faith, the catacombs were born.

In the Middle Ages, every trace of the catacombs was lost, along with the memory of their entrances—save for the cemeteries that had grown above the major basilicas. What rekindled interest in these underground labyrinths was the chance discovery of some along the Via Salaria Nuova in 1578, among them the famed Catacombs of Priscilla.

Reconstruction of a burial site along a Roman consular road and the interior of a catacomb.

Today, the term catacombs (from catacumba) refers to the ancient underground Christian cemeteries used by the early followers of Christ to bury their dead, beginning in the 1st century AD. Yet in antiquity, this word was not used to describe them. Any Christian burial site—whether subterranean or aboveground—was simply called a cemetery (coemeterium).

The name catacomb first appeared in the 4th century AD, designating a particular underground site in Rome, now beneath the Basilica of St. Sebastian: the phrase ad catacumbas originally referred to the natural hollow or depression in the terrain along the Appian Way where is the Basilica. By the Middle Ages, the term had expanded to encompass all underground Christian cemeteries that also served as places of worship.

Christian catacombs are vast subterranean networks typically carved into soft, workable rock like tuff, allowing for multi-level construction that could reach depths of up to 40 meters. Their walls are lined with thousands of loculi—horizontal niches stacked one upon another to hold the deceased. Wealthier Roman citizens, however, used cubicula—family tombs recessed into the walls, often adorned with frescoes. These were protected under Roman private law, as tombs were considered locus religiosus (sacred ground), regardless of ownership.

Though Christian catacombs exist worldwide, the most significant are found in Rome and Naples. Some scholars speculate that after Emperor Valerian’s persecutions (257 AD), Christians hid in these tunnels for extended periods. Yet this seems unlikely—despite ventilation shafts, the air would have been unbreathable beyond a few hours, turning toxic. Moreover, the buried bodies, though sealed with mortar, emitted gases that cracked the tombs, releasing foul odors.

Originally, catacombs were separate, primitive burial nuclei, each with its own entrance, later interconnected to form communal cemeteries. Wealthy landowners permitted fellow believers to bury their dead there, and liturgical gatherings were held within.

Of Rome’s 60+ catacombs, only seven are open to the public today. Among them is the Catacomb of Priscilla, the oldest Christian cemetery in Rome, dating back to the Apostolic Age. One of its earliest nuclei was the hypogeum of the family of Manius Acilius Glabrio.

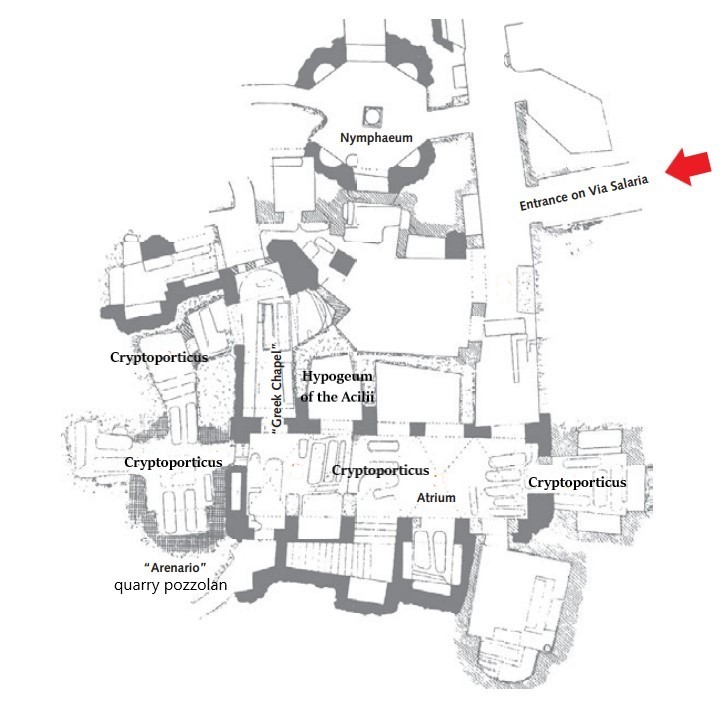

Entrance to the Catacombs of Priscilla.

Manius Acilius Glabrio (ca. 55–95 AD) served as consul in 91 AD alongside Marcus Ulpius Trajan, the future emperor. He was persecuted by Domitian for the "crime of atheism" (likely Christianity) and executed. Legend claims Domitian forced Glabrio to fight a lion; when he emerged victorious, the emperor’s envy turned to hatred, leading to his exile and execution around 95 AD. While Juvenal and Suetonius claim he was accused of aspiring to the throne, Cassius Dio suggests it was due to his Christian faith. Most likely, Glabrio and his relatives were condemned for converting to Christianity.

His wife was Arria Plaria Vera Priscilla, as it is attested by an extant inscription (CIL VI, 6333), and we know that their son became consul in 124 AD.

Catacomb of Priscilla

The Catacomb of Priscilla: Regina Catacumbarum

This catacomb holds around 40,000 burials. Abandoned in the 5th century and plundered during barbarian invasions, its entrances were sealed and forgotten until its rediscovery in May 1578. Among the first catacombs found in the 16th century, it was heavily looted for tombstones, sarcophagi, tuff, and relics; yet it still preserves stunning early Christian art. It is the Regina Catacumbarum (Queen of the Catacombs) for the sheer number of martyrs and popes interred here between 309 and 555 —many were victims of Diocletian’s brutal persecution (284–305 AD).

• Popes: Marcellinus (296–304), Marcellus (308–309), Sylvester I (314–335, who built the basilica above), Liberius (352–366), Siricius (384–399), Celestine I (422–432), and Vigilius (537–555).

• Martyrs: Felix and Philip; two sons of St. Felicitas; Crescentius; Prisca; Pudentiana and Praxedes; Paul; Maurus; Semetrius; and 360 unnamed martyrs.

Located 2.5 km from Rome’s center on the Salaria Nova, the catacomb sprawls beneath the ancient estate of the gens Acilii, an aristocratic Roman senatorial family of which Priscilla was part, the noblewoman from whom the catacomb is named and who perhaps donated the land. By the 2nd century AD, Rome faced overpopulation and land scarcity. Christians, rejecting pagan cremation, turned to communal underground cemeteries. After the 5th century, burials moved aboveground, and the catacombs became pilgrimage sites.

Excavated in sandstone, Priscilla’s catacombs span 13 km of labyrinthine galleries across two levels (35 meters deep).

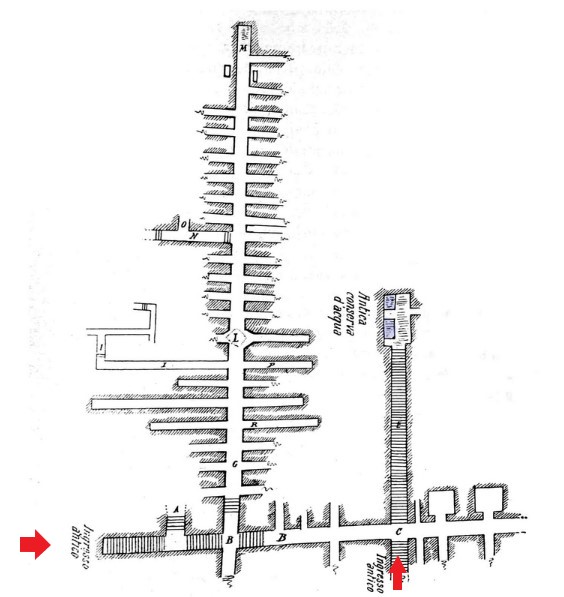

Upper level of the Catacombs of Priscilla.

The oldest, upper level includes:

• The Arenario: A pozzolana quarry repurposed for collective burials, perhaps already in existence in the first half of the third century under Caracalla (211–217 AD). Here lies the oldest known image of the Virgin Mary (2nd–3rd century), seated with the Child, alongside the prophet Balaam (or Isaiah) pointing to a star.

The Cubiculum of the Veiled Woman. This chamber takes its name from the depiction of a "veiled woman" painted in the back lunette, shown in a prayerful posture. The scenes portrayed here—unique in early Christian art—are interpreted as key moments in the deceased woman’s life: marriage, motherhood, and her admission among the blessed. The frescoes, dating to the second half of the 3rd century, include depictions such as the Good Shepherd among birds and salvation scenes from the Old Testament, including the Prophet Jonah, the Three Young Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace, and the Sacrifice of Isaac.

Nearby is the well-known chamber called the Cubicle of the Velatio. At the center of its vault, the image of the Good Shepherd is enclosed within a medallion, surrounded by various species of birds. The entrance and side walls feature scenes from the Old Testament, including Jonah, The Sacrifice of Isaac, and The Three Young Hebrews in the Furnace.

The lunette at the back depicts a veiled female orant (a praying figure) at its center. To her right is a woman with a child, while to her left sits a figure before whom two others stand. It is widely believed that this final scene represents The Consecration of the Virgin, while the opposite side portrays The Madonna and Child.

The Oldest Depiction of the Virgin Mary. Considered the oldest in the world, this image has been dated to the early 3rd century (230–240 AD). The painting shows the Virgin with the Child and a prophet pointing to a star above her head. This figure may be identified as the Old Testament prophet Balaam, who foretold the coming of Christ.

• The Cryptoportico: This vaulted gallery was likely originally the cryptoporticus (underground corridor) of a villa that once stood above it. The "Greek Chapel" (dating to the second half of the 2nd century AD) derives its name from the Greek inscriptions painted in its main chamber. The space is a long hall with three apses at the rear, divided into two sections by a large arch. It served as a burial chamber, richly decorated with frescoes and stuccos.

High on the entrance facade, there is a depiction of Moses striking water from the rock. Above him is a bust, possibly a portrait of the deceased, flanked on the left by the Three Young Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace and on the right by an unidentified figure.

The large dividing arch features the Madonna and Child with the Magi, while the side walls illustrate episodes from the story of Susanna. The vault in the second half of the room is adorned with vine tendrils and four figures—two in prayer.

Above the apse, an unusual banquet scene includes a rare depiction of a woman. Opposite this, the Resurrection of Lazarus is portrayed. The right side shows Daniel among the lions and Noah, while the left depicts the Sacrifice of Isaac. These frescoes likely date to the late 3rd century at the earliest.

Among its treasures is the Fractio Panis fresco, a masterpiece depicting a Eucharistic-like meal.

The cryptoporticus is one of the oldest sections of the catacomb. It leads to the famous "Greek Chapel," with frescoes dating to the reign of Emperor Gallienus (253–268 AD). The chapel is decorated with scenes from the story of Susanna, the Adoration of the Magi, and a well-known banquet scene known as the Fractio Panis (Breaking of the Bread).

• The Hypogea:

- Hypogeum of Eve: A gallery with a rare depiction of Eve.

- Hypogeum of the Acilii: Once thought to belong to the family, it was later decorated with mosaics (early 4th century). It is a large room, identified as the tomb of the Acilii and of Priscilla on the basis of several inscriptions, which refer to Priscilla as a clarissima femina (thus a member of the Roman aristocracy) and name other members of the family. In fact, the room is not a burial place but a cistern, and the inscriptions of the Acilii probably come from the ground level above.

Lower level of the Catacombs of Priscilla. Schematic plan of a section of the lower level, containing an ancient water cistern..

The lower level of the catacomb is formed by very long longitudinal tunnels intersected at right angles by a series of transverse tunnels.

The catacomb galleries of Priscilla

Between the two levels there is an intermediate identifiable by some scholars with the cemetery of Novella.

Pope Sylvester (314–335) built a basilica above the tombs of martyrs Felix and Philip, and Damasus (366–384) added inscriptions honoring them. By the 6th century, the site was known as Coemeterium Priscillae ad Sanctum Silvestrum.

The Basilica of San Silvestro. Excavations above the Catacombs of Priscilla have uncovered the foundation walls of a basilica built over the tomb of Pope St. Sylvester, who was elected in 314 AD.

Rome, Via Salaria, 430

catacombepriscilla.com