The nameless martyr at the Catacombs of Commodilla

Rome, Italy

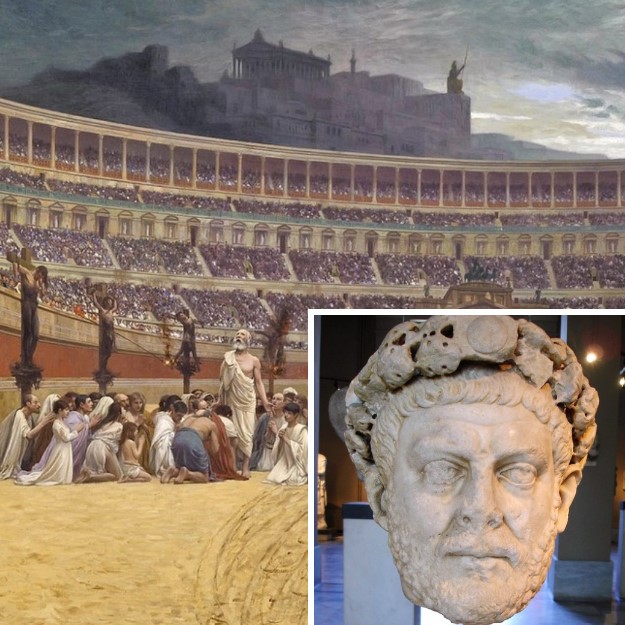

The Diocletianic Persecution (or Great Persecution) was the last and most severe persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. In AD 303, the emperors Diocletian, Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius Chlorus issued a series of edicts aimed at revoking the legal rights of Christians and compelling them to conform to traditional Roman religious practices. Subsequent edicts targeted the clergy and demanded "universal sacrifice," ordering all inhabitants to offer sacrifices to the pagan gods.

Christians had long faced local discrimination within the empire, but earlier emperors were reluctant to enact general laws against them. This changed in AD 250 under Emperors Decius and later Valerian, when such laws were passed. Under this legislation, Christians were forced to sacrifice to the Roman gods or face imprisonment and execution. In contrast, Gallienus issued the first imperial edict of tolerance toward Christians in 260, leading to nearly 40 years of peaceful coexistence. Diocletian’s rise to power in 284 did not immediately reverse official disdain for Christianity, but it gradually shifted state attitudes toward religious minorities. In the first fifteen years of his reign, Diocletian expelled Christians from the army, sentenced Manichaeans to death, and surrounded himself with public opponents of Christianity. Diocletian’s preference for activist governance, combined with his self-image as a restorer of Rome’s past glory, foreshadowed the empire’s most widespread persecution. In the winter of 302, Galerius urged Diocletian to initiate a general persecution of Christians. Diocletian, wary, consulted the oracle of Apollo for guidance. The oracle’s response was interpreted as endorsing Galerius’ position, and a general persecution was proclaimed on February 24, 303.

The intensity of persecution varied across the empire. While Galerius and Diocletian were relentless persecutors, Constantius was unenthusiastic. Later persecutory edicts, including demands for universal sacrifice, were not enforced in his domains.

The persecution failed to curb the growing influence of the Church. By 324, Constantine—now sole Roman emperor—made Christianity his favored religion. Though the persecution caused thousands of Christian deaths, and torture, imprisonment, or displacement for many others, most Christians avoided punishment.

In subsequent centuries, some Christians cultivated a "cult of the martyrs," exaggerating the barbarity of the persecution era.

Istanbul - Archaeological Museum - Statue head of the Roman emperor Diocletian (284-305 AD)

The Legend of Felix and Adauctus

According to a 7th-century legendary Passio, Felix was a Roman presbyter arrested as a follower of Christ during Diocletian’s persecution in the early 4th century. He was taken to the Temple of Serapis to sacrifice to pagan idols; Felix blew on the statue, causing it to collapse, and the same occurred with statues of Mercury and Diana. This display of divine power led to his torture and death sentence.

En route to Ostia, just outside Rome near a large tree consecrated to the gods and an adjacent temple, he was again urged to sacrifice. Felix commanded the tree to fall onto the temple, destroying it—which it did.

The procession continued toward the execution site. At one point, a young man pushed through the crowd, declaring his wish to die like Presbyter Felix by spontaneously confessing his faith. Both were led to decapitation at a spot near present-day Via di S. Adautto.

quod sancto martyri Felici auctus sit ad coronam

— Life written by Ado in his Martyrologium (9th century)

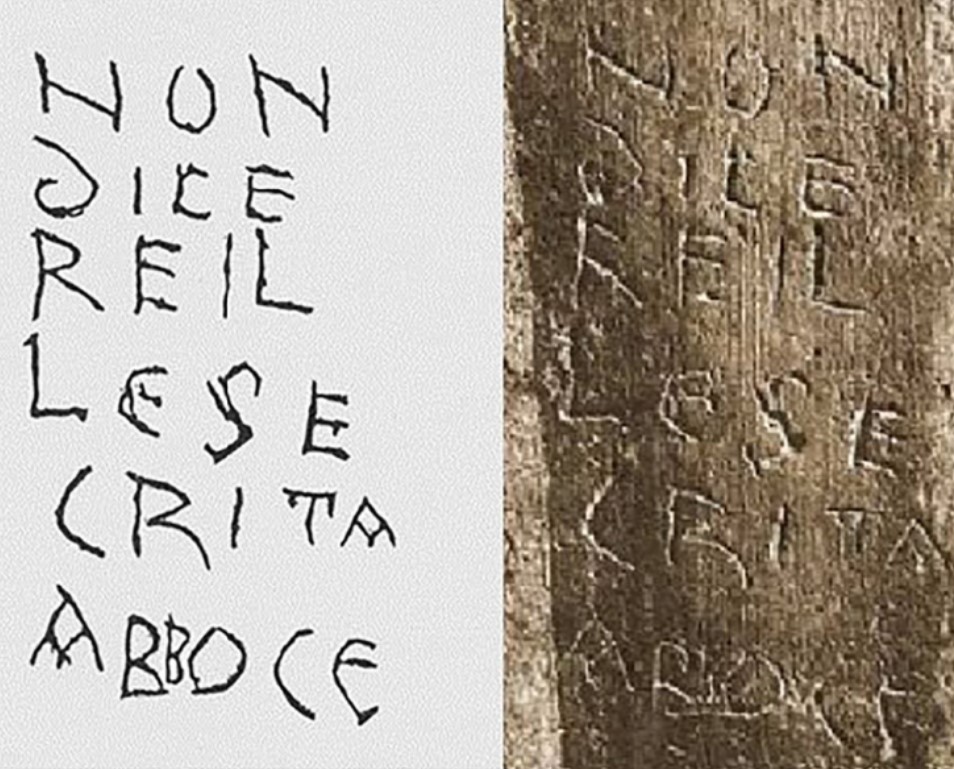

Since the young man’s name remained unknown, he was nicknamed Adauctus (from Latin adiutum, "added"), later rendered Adautto. He is likely the martyr buried with Felix in a crypt in the Catacombs of Commodilla on the Via Ostiense, close to San Paolo fuori le Mura. Here, within the frame of a fresco (6th–7th century AD), a 9th-century graffito behind the altar reads:

Non dicere ille secrita a bboce

Do not speak secrets aloud

This instruction warns the faithful not to confess "the secrets"—i.e., the Christian faith—"aloud," lest they end up martyred like Adautto.

Inscription from the 9th century, Catacomb of Commodilla, Rome

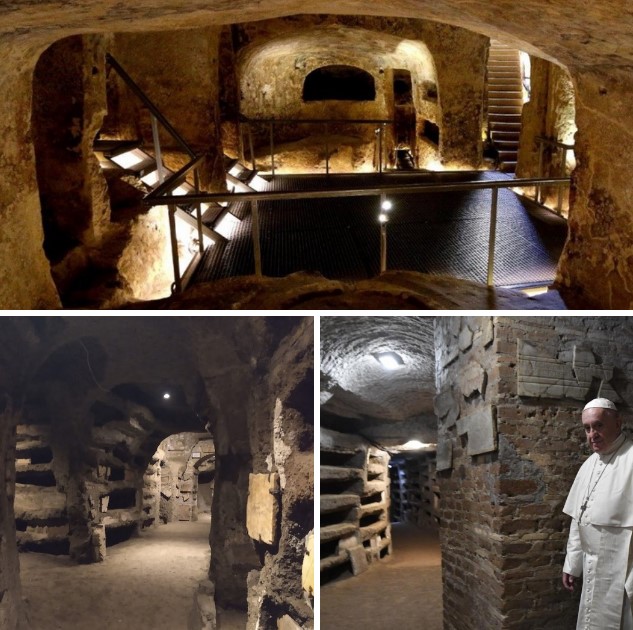

Commodilla Catacombs: Rome’s Hidden Sanctuary

The catacomb’s name, like most Roman catacombs, derives from its owner and donor, Commodilla. Created by repurposing galleries from a pre-existing pozzolana quarry, it is a fascinating labyrinth of ancient Christian cemeteries dating from the 2nd to 4th centuries AD.

Plan of the Catacombs of Commodilla, Rome

The subterranean cemetery spans three levels. The oldest is the middle level, carved from the ancient pozzolana quarry—this level contains the martyrs’ tombs and serves as the nucleus from which the rest of the catacombs branch. Its original entrance (now sealed) was opened into a hillside slope at the end of the main gallery. Opposite this, in three distinct points along the same gallery, three martyrs of Diocletian’s persecution were buried: Felix, Adautto, and Merita.

No above-ground monuments or remains connected to the catacombs exist to aid pilgrims in locating them.

Artifact analysis dates the catacombs to the 4th century AD, while the martyrdom of Felix and Adautto occurred in the final years of Emperor Diocletian (284–305). This suggests the pozzolana quarry was partially used for burials before its closure and conversion into a cemetery. The catacombs were used for burials no later than the end of the 4th century; during the 5th and 6th centuries, they served only devotional purposes.

Transformation

Popes John I (523–526) and Leo III (795–816) restored and embellished the site. It houses one of the oldest Paleochristian frescoes (6th century), depicting the two martyrs alongside Saints Peter, Paul, and Stephen.

The episode remained vivid in the Roman Church’s memory, which commemorated both names jointly. Their veneration as saints dates back at least to the 4th century and is documented by a poem dedicated to them by Pope Damasus I (305–384).

Later, like other Christian underground cemeteries, the Catacombs of Commodilla became a martyrial shrine. In the 4th century, a lateral gallery was opened to the right of the martyrs’ burial chamber. This gallery was repeatedly deepened and extended to allow the faithful burial near the martyrs’ tombs. The crypt housing Felix and Adautto was reinforced with supporting walls by Pope Siricius (384–399), transforming it into a true small basilica (called basilichetta due to its form) by enlarging the saints’ original cubiculum. During this work, the entrance to the lateral gallery was sealed, rendering it inaccessible. It was rediscovered intact during 20th-century excavations, with sealed loculi and valuable funerary goods.

The crypt remained a pilgrimage destination well into the Middle Ages before catacombs and underground memorials fell into oblivion.

Underground chapel with the tombs of martyrs Felix and Adautto. Catacombs of Commodilla, Rome

Rediscovery

For centuries, the catacombs remained inaccessible until partially discovered and explored in 1595.

In 1720, they were accidentally rediscovered when the crypt resurfaced. Paintings of the entombed martyrs—still visible at the time—enabled their identification as Commodilla’s. Days later, a massive landslide reburied them.

In 1904, while the cemetery lay buried beneath Cavaliere Giuseppe Serafini’s vineyard (now a public garden along today’s Via delle Sette Chiese, stretching from the Basilica of San Sebastiano on the Appian Way to the Basilica of San Paolo), excavations approved by the landowner reopened this religious monument. The dig revealed not only the crypt but also the historic access staircase, a narrower parallel staircase (running in the opposite direction), and a large portion of the surrounding underground cemetery.

At the rear of the crypt stood a grand tomb beneath an apse adorned with paintings, mosaics, and ancient visitor graffiti. This tomb held three burial spots: two side-by-side in a niche, and a third separate one in the wall. This suggested Saints Felix and Adautto occupied the first, and Saint Emerita the other. Traces of 4th- or 5th-century paintings remained visible on the tomb: facing front, the two local saints gestured toward Christ’s monogram; to the right, their coronation alongside Saint Emerita. To the right was a large niche likely housing the altar, and beside it another niche probably holding a lamp table. A metrical inscription near the martyrs’ tomb noted that a priest named Felix (namesake of the martyr) undertook major renovations under Pope Siricius (385–398).

Numerous burial niches were carved into the crypt walls and beneath its floor, demonstrating deep devotion to these martyrs. This devotion was further evidenced by a 4th-century gallery excavated beside the shrine—sealed for centuries, it was found almost perfectly preserved, with sealed loculi still containing terracotta lamps set in mortar.

Three tombs in the crypt were particularly important and decorated with paintings:

• The first tomb, toward the rear, belonged to a woman named Turtura. Her tomb featured a beautiful, intact Byzantine-style fresco (6th century) depicting the deceased before the Virgin Mary enthroned with the child Jesus, flanked by the local saints Felix and Adautto, labeled:

SCS FELIS (sic) SCS ADAVTVS.

Wall painting from the Catacombs of Commodilla in the so-called Tomb of Turtura, mid-6th century. The fresco depicts the Madonna and Child seated on a golden stool, with the figures of Saints Felix and Adautto and the donor, Turtura. An inscription runs along the lower border: "Your name is Turtura, and truly you were a real turtle-dove."

• The second tomb was a loculus painted to imitate colored marble, bearing a painted inscription of a Quadragesima and the date 432.

• The third tomb, near the crypt entrance, also featured a 6th-century painting depicting the Savior giving keys to Saint Peter (SCS PETRVS). To the left stood Saint Paul (SCS PAVLVS) holding his epistles, then Saint Felix (SCS FELIX) with a crown. Beyond Saint Peter were traces of another saint’s effaced figure. This scene was flanked by figures of Saint Stephen (SCS STEFANVS) and Saint Emerita (SCA MERITA), beneath whom palm trees were painted. Beneath this scene, above a loculus in the lower wall, faint traces of an older red-painted inscription read:

SANCTO MARTYRI BENERABILI (sic)

Since pilgrim itineraries mention another unknown martyr named Nemesius venerated in the same ecclesia as Felix and Adautto, this was likely his tomb.

Another significant monument was discovered in the gallery connecting the historic crypt to the main staircase: an arcosolium tomb cut into the wall by demolishing older tombs. Its opening was adorned with a 6th-century painting of Saint Emerita between the two local saints. This tomb likely belonged to a 6th-century devotee who sought burial near the martyrs.

This cemetery revealed numerous uniquely shaped tombs. In its central region, square shafts roughly 2 meters deep were dug along gallery edges. Their four walls held loculi for corpses. Similar openings in gallery vaults served as light wells (luminaria), their walls also lined with loculi. In wider lateral galleries, half the floor was deepened to create a narrower sub-level gallery, its walls entirely occupied by loculi. The fossors (diggers) of this catacomb clearly devised innovative methods to maximize burial space in a confined area—driven by the faithful’s desire to be buried near martyrs’ tombs, whose powerful intercession they sought for entry into Christ’s heavenly kingdom.

Shortly after WWII, children crafted an improvised ball from old bike pedals, nylon stockings, and rags. While testing it near the Serafini vineyard, the ground gave way, forming a large hole about two meters wide. Peering inside, they saw a corridor-like space. Without hesitation, five or six children climbed down into the pitch-dark, damp, silent space. Brushing away red earth, they discerned a well-excavated tunnel. Darkness forced them to retreat, but they returned the next day with makeshift torches (old bicycle tires tied to sticks). The smell and smoke prompted them to move quickly. After fifteen tense minutes, they saw light ahead—they emerged near the Rocca di San Paolo, close to the Basilica, in an area with three WWII air-raid shelters. The children had discovered a new funerary region with a cubiculum, fully painted with biblical scenes, owned by Leo, an annona official (380–390).

Cubiculum of Leo, Catacombs of Commodilla, Rome

The cult of Saints Felix and Adautto spread to Northern Europe after Pope Leo IV (847–855) gave relic fragments to Ermengarda, wife of Lothair I, who carried their veneration north of the Alps. It reached as far as Kraków, where a royal palace chapel is dedicated to them.

The relic of Saint Adautto’s head is now enshrined at Santa Maria in Cosmedin alongside other martyr relics: Angelo Fanciullo, Benedict, Benignus, Candida, Candido, Concordia, Desirio, Desiderio, Julian, Hippolytus, Placidus, Romanus, and Valentine. This relic, placed in a 6th-century altar in the crypt, is displayed adorned with roses.

An 1870 inventory further lists skull relics of martyrs Adrian, Amelia, Antoninus, Clemency, Generosus (two), Octavius, and Patricius. It also mentions the leg of Olympias and that of Saint John Baptist de Rossi.

Catacombs of Commodilla and Pope Francis Visiting the Tomb, Rome

Rome, Via delle Sette Chiese, 42