The Acquaroli: Water Sellers Who Peddled to the People the Water Popes Took on Their Journeys

Rome, Italy

Until the mid-16th century, the Tiber River was the sole source of water for the Romans. This was because, with the exception of the Vergine aqueduct – which, albeit intermittently, supplied water to central areas of the city – the ancient Roman aqueducts had been out of use for over a thousand years. In the past, Tiber water was considered not only drinkable but also healthful. This practice of drinking it lasted until the early 1800s.

Even the popes relied on Tiber water, preferring it to well water, which was available only in limited quantities from wells scattered within the Aurelian Walls. Indeed, there were popes like Clement VII (1478-1534) on the advice of his doctor, Paul III (1468-1549), and Gregory XIII (1502-1585), who habitually carried containers of river water with them on their journeys. They were also convinced by the assertions of so-called "Tiberine doctors," who claimed the river's water was not only excellent but the best table water if properly treated before use.

The consequences of such hygienic theories were disastrous: while the water was a vector for infections and plagues, its presumed healthfulness also dissuaded the popes from investing resources in reactivating the ancient aqueducts, as these would have constantly drained money for necessary maintenance. Instead, several popes like Paul III preferred to allocate substantial funds to adorn the city with magnificent palaces and countless ornaments, and to keep the streets clean.

By the 17th century, the river water no longer enjoyed the same regard across all levels of society. The Florentine doctor Giovanni Battista Modio, in his treatise on the qualities of Tiber water, refuted its established healthfulness and denounced the state of the Roman aqueducts. Meanwhile, monk Jacopo Castiglione, in his treatise on the Tiber floods, clearly explained his opposition to the river water's use: he linked the occurrence of floods to epidemics of plague and famine, describing the disastrous flood that hit the city in 1598 and suggesting some solutions to the problem.

In reality, the failure to restore the ancient Roman aqueducts over the centuries wasn't solely due to the popes; it was also because all Romans could access cheap water directly from the Tiber. This is without even considering the small multitude of people who made their living from the trade in river water, which was widespread throughout the city streets. An anonymous 16th-century sonnet aptly captures the water seller's trade:

This traffic Pasquino taught to me, to sell water to buy wine.

This trade reached its peak in the early 16th century, coinciding with increasingly repeated recommendations from doctors to use Tiber water only after a period of decantation. That is, before drinking it, the water needed to rest for about six months in suitable basins – also called vettine, conserve, or terracotta jars – until the fine sediment that gives the river its blond color had completely settled to the bottom. However, decantation equipment was actually only owned by nobles and high prelates like cardinals, who had cisterns beneath their palaces where the water aged and purified, becoming clear.

The common people, however, stored it in jars; thus they drank it cloudy and impure, heedless of their health. Those who could afford it resorted to the so-called acquaroli (water carriers) who sold pre-decanted water. These were street vendors who, using small barrels transported by donkeys, distributed water throughout Rome's neighborhoods. They offered various types of water, both from wells and other streams flowing through the city. Naturally, the water merchants were immensely popular and entered countless homes daily; indeed, numerous families reportedly had monthly contracts with them.

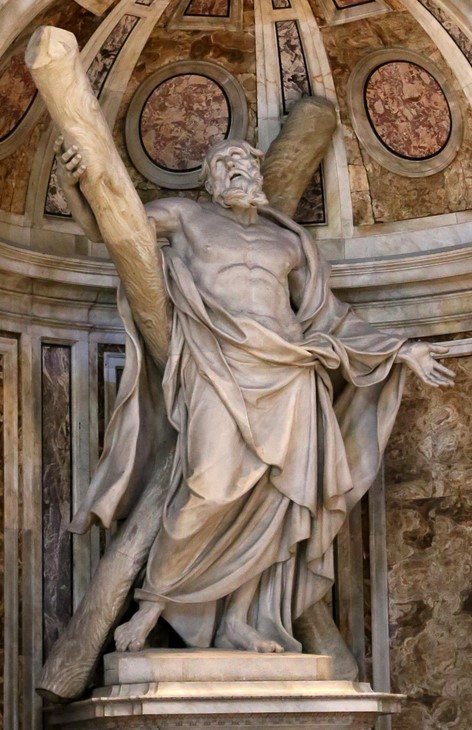

Statue of Saint Andrew by François Duquesnoy (1640), in St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican.

This trade likely existed since the Middle Ages and was so deeply rooted that the acquaroli themselves formed a guild under the protection of Saint Andrew the Apostle. Saint Andrew and his brother Peter were fishermen, and tradition holds that Jesus himself called him to be his disciple by inviting him to be a "fisher of men" (halieus anthropon), also translated as "fisher of souls." He was martyred by crucifixion in Patras (Patrae), Achaia (Greece), probably in 60 CE during Nero's reign. It is known that Andrew was bound, not nailed, to a Latin cross (similar to the one Christ was crucified on), but tradition holds that Andrew was crucified on a cross called a Crux decussata (X-shaped) and commonly known as the "Cross of Saint Andrew." This was adopted by his own choice, as he would never have dared to equal the Master in martyrdom. After his martyrdom, according to tradition, his relics were translated from Patras to Constantinople, though local legends claim they were sold by the Romans.

The façade of Santa Maria della Pace in an engraving by Giuseppe Vasi (18th century).

In the 15th century, the acquaroli had their own chapel dedicated to Sant’Andrea de Aquarizariis (Saint Andrew of the Water Carriers, upon whom the city depended after the aqueducts broke). Their chapel, although well-attended, was confined to a cramped and poorly accessible space. It was located on a narrow medieval street almost inaccessible to carriages, which had to reach it from Via Tor Millina, Via dell’Anima, and Via dei Coronari. The latter two were blocked by bollards because there wasn't enough space for two vehicles to pass each other, forcing them to stop in Via della Pace to maneuver and turn around in the small square in front of the church entrance.

In 1482, a drunk soldier passing by threw a stone at the image of the Virgin Mary located under the porch of the chapel (today placed on the high altar), and it miraculously bled. Pope Sixtus IV wanted to see the occurrence for himself and was so impressed that he changed the chapel's name to St Mary of Virtue. Seeing that it was in deplorable condition, he also promised to restore it, undergoing significant transformations. Sixtus IV was forced to demolish many medieval houses in the small square to allow for the renovation work.

Later, another Pope, Innocent VIII, changed the name of the church again to its current one, Church of St Mary of Peace, to commemorate the Peace of Bagnolo, which had ended the war between the Papal State, Venice, and the Kingdom of Naples.

Virgin Mary, Church of St Mary of Peace

Over the centuries and almost until the end of the 19th century, the Tiber represented an essential water resource for the Romans, a transportation route, a place for secular and religious festivals, and a spot for leisure time. Particularly, its banks were favorable locations for a flourishing river economy, organized into crafts and trades that inherently depended on the presence of water: water sellers (acquaroli), tanners (vaccinari - leatherworkers), potters (vascellari - makers of terracotta vessels), dyers, boat builders, ferrymen (barcaroli), millers (molinari), fishermen, hauliers (pilorciatori - those who towed boats), woodcutters (legnaroli), sailors and port workers, washerwomen (lavannare), sand dredgers (renaroli), and river folk (fiumaroli - those who lived on the Tiber and derived their livelihood from various river-related jobs, such as recovering objects fallen into the water for a fee). These workers crowded into dilapidated houses along the river, shaping the toponymy of the areas, still visible today in places like Via dei Vascellari in the Trastevere neighborhood (Rione XIII) or Via di S. Bartolomeo dè Vaccinari in the Regola neighborhood (Rione VII). The combination of these and other activities constituted an important source of income for citizens, contributing to making the Tiber a familiar presence, a beloved place, tightly interwoven with the city's daily life. Over the centuries, the ancient name acquari changed to acquarenarii, likely derived from the sandy (arenosa) water of the Tiber drawn upstream of the city near Milvian Bridge, referring to the purification from sandy sediments performed before sale.

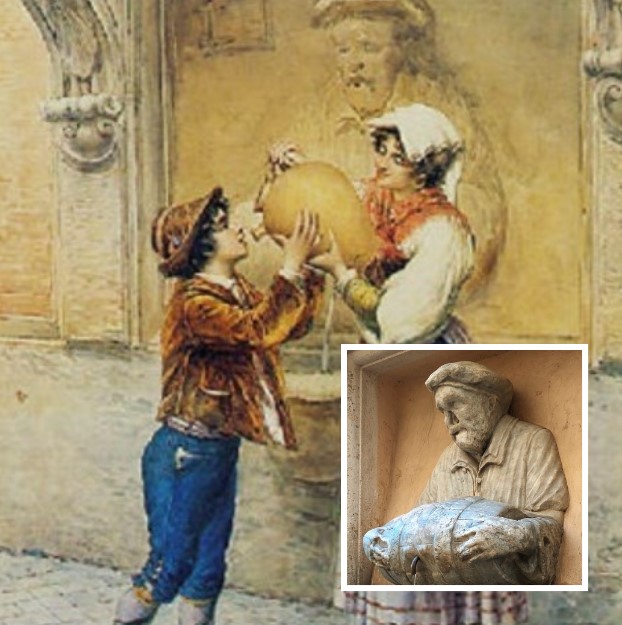

In the 19th century, there was also a second place where water sellers drew water from the river: near Tor di Nona, in an area adjacent to Via dell’Orso, called the Porto degli Acquaroli (Water Carriers' Port). The same toponym later designated two other small ports in central Rome: one located in the Ghetto near Bridge Four Heads, the other near Piazza Padella (Via Giulia). Although the term porto degli acquaioli seems to suggest landing places for small boats bringing water into the city, it actually simply marked the locations of systematic water withdrawals from the Tiber. The popularity of the water seller is also attested by the Fontana del Facchino (Porter Fountain), datable, according to Cesare D’Onofrio, to around 1580, when the Vergine aqueduct had been partially reactivated. Traditionally attributed to the design of the Tuscan painter Jacopino del Conte (1510-1598), the fountain depicts a water carrier holding the half-barrel, the tool of his trade, wearing the typical attire of 16th-century water carriers or porters (facchini). These men would fill barrels and small kegs at night with water drawn from the Tiber or the ancient Trevi Fountain to distribute it to the Romans during the day in exchange for a modest fee.

18th-century Roman landscape with the Milvian Bridge by Paolo Anesi (1697–1773).

The identity of the porter became the subject of various extravagant legends: some believed it depicted Martin Luther, who stayed in the nearby Augustinian monastery adjacent to Santa Maria del Popolo in 1511; others thought it was a certain Abbondio Rizzio, who died while carrying a barrel and is also mentioned in a Latin inscription, once placed above the fountain and now removed, which read:

Ad Abbondio Rizio, coronato [facchino] sul pubblico selciato, valentissimo nel legar fardelli. Portò quanto peso volle, visse quanto poté; ma un giorno, portando un barile di vino in spalla e dentro il corpo, contro la sua volontà morì.

To Abbondio Rizzi, crowned [porter] on the public pavement, most skilled in tying bundles. He carried as much weight as he wished, he lived as long as he could; but one day, carrying a barrel of wine on his shoulder and with wine inside his body, against his will he died.

The Fontana del Facchino and a 1637 engraving by Domenico Parasacchi showing the original features of the porter's face before its defacement.

From the 17th century onwards, along with Pasquino, Marforio, Abbot Luigi, Madama Lucrezia, and Babuino, the Facchino became part of the "Congress of the Wits" (Congresso degli arguti), Rome's famous talking statues. Perhaps for this very reason, its face was vandalized, likely as early as the end of the 17th century. A 1637 engraving by Domenico Parasacchi shows the original facial features before the defacement. Regarding the choice of subject, it's also worth noting that in the immediate vicinity of the future fountain, there were shops belonging to porters originally from Valtellina who, again according to D’Onofrio, traded in water. The fountain was originally attached to the painter's residence – on the façade of Palazzo dei Grifoni opposite the church of Saint Marcello – at the corner between Via del Corso and Via di Santa Maria in Via Lata, near the palace of the powerful Florentine Salviati family. It was supplied by the Vergine aqueduct, which branched off from the Corso with a segment leading towards Piazza dell’Arco di Camigliano. It was framed by an architraved niche and had a wider basin below.

The Porter Fountain

The Fontana del Facchino was semi-public, and according to a bold 1751 statement by Luigi Vanvitelli (1700-1773), it had been sculpted by Michel’Angelo Buonarroti. In reality, we know that Jacopino del Conte's house was part of a block largely owned by the Grifoni family, Tuscans with strong loyalty to the Medici. For the Grifoni, who inhabited the block according to documents from at least 1567 (but reasonably from the mid-16th century), the sculptor Stoldo Lorenzi (1534-1583), creator of the porter, was also active. Moreover, the possible Florentine origin of this type of popular depiction, with grotesque touches, finds convincing parallels in statues scattered throughout the Boboli Gardens. Indeed, that block seems to have hosted a Florentine colony, particularly several members of the Grifoni family; recall that Michelangelo had designed a project for a residential building (hypothesized for a non-Florentine residence) for this family.

The fountain's life was not peaceful, however. After Livio De Carolis acquired all the properties in the block and the subsequent construction of a large residential building by Alessandro Specchi (1666-1729), the fountain was dismantled in 1724 and remounted still on the Corso, until its current placement on the side street in 1872. It was then moved to the adjacent Via Lata, attached to the wall of Palazzo De Carolis, to save it from carriage collisions and stones thrown by street urchins.

Rome, Via Lata 5