Villa Florio in Rome: The Last Splendor of a Fading Empire

Rome, Italy

The Florios were a family of Calabrian origin who moved to Palermo in the late 18th century and, over the course of the 1800s, rose to extraordinary economic prominence—eventually becoming one of Italy’s first industrial dynasties and entering the exclusive circle of international financial aristocracy. Their members were described as lions—proud and indomitable—who managed to assert themselves in a turbulent Sicily and a rapidly transforming Europe during the so-called Belle époque.

Vincenzo Florio Sr. (1799-1868) with his wife, Giulia Portalupi, and his son, Ignazio Florio Sr. (1838-1891), with his wife, Giovanna D’Ondes Trigona

The earliest historical records of the family date back to the mid-17th century, tracing their lineage to the patriarch Tommaso Florio (c. 1650–1725), a blacksmith and farrier from Melicuccà. The 1783 Calabrian earthquake claimed several family members and left the survivors in ruin. Forced to abandon their homeland, they sought fortune in nearby Sicily, where they took over a Palermo shop selling spices, colonial goods, and quinine—used to treat malaria. The aromatary soon became one of the city’s most prosperous businesses. But the Florios were not content; they had a visionary impulse to expand into tuna fisheries.

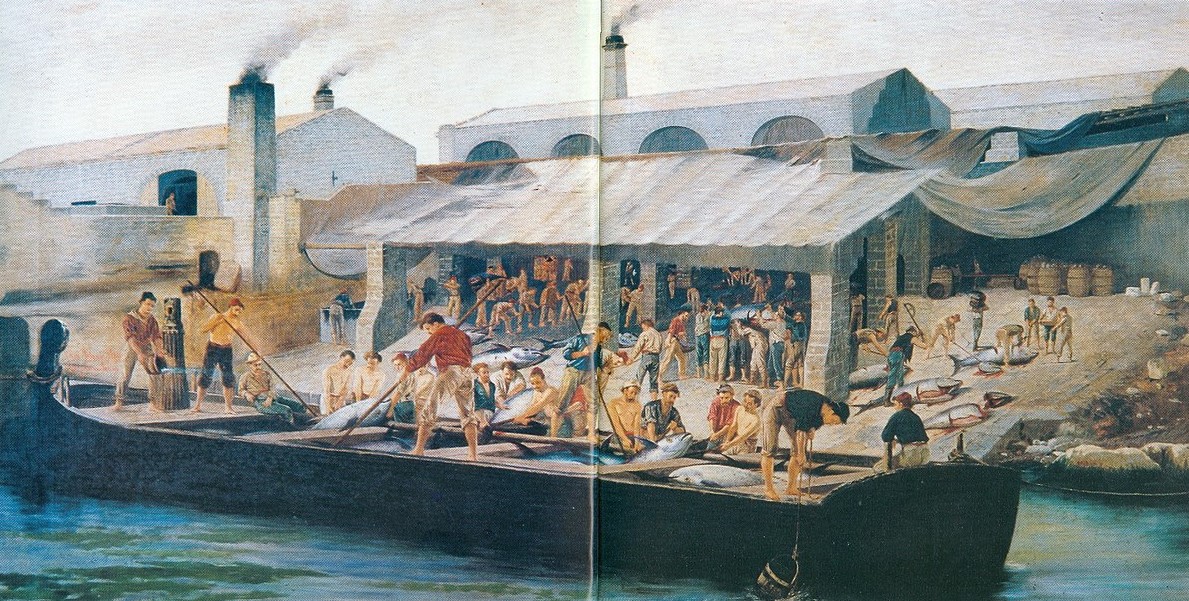

"The Tonnara of Favignana" by Antonio Varni (1841–1908), 1876.

By the early 19th century, the Florios had launched numerous successful industrial ventures, including winemaking, tobacco, cotton, and steamship lines reaching as far as America. They revolutionized the production of Marsala, the fortified wine named after the coastal city, which was already gaining international acclaim. Toward the century’s end, they made another groundbreaking move: instead of preserving tuna in salt—the standard practice—they pioneered canning it in oil. Their factories employed countless workers and spread their products across the globe.

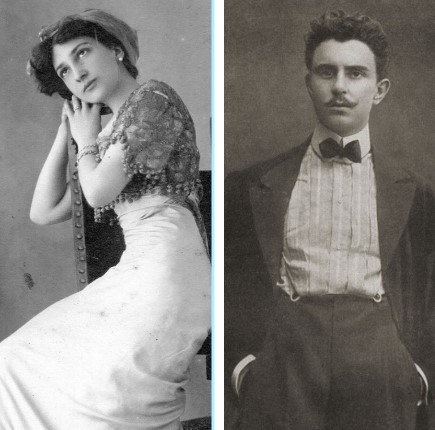

Vincenzo Florio Jr. (1883–1959) and Annina Alliata di Montereale (1885–1911) – his first wife, who died tragically young of cholera just two years after their marriage.

Though of Calabrian descent, the Florios were deeply intertwined with Sicilian history. Through commerce and patronage, they helped shape the island’s economic and cultural identity. Their story—marked by triumphs and trials, ascents and declines—stands as a testament to determination, ingenuity, and entrepreneurial vision. The family’s backbone was its formidable women: elegant, envied, always a step ahead of their men, whether those men were visionary tycoons or bohemian adventurers.

Portrait of Donna Franca Florio, made by Giovanni Boldini – 1903

The most dazzling of them all was Franca Florio (1873–1950), wife of Ignazio Florio Jr. (1869–1957). Born Francesca Jacona della Motta di San Giuliano, she was a noblewoman descended from Sicilian aristocracy. Beloved and admired by all, she was wise, intelligent, and the undisputed queen of high society—a woman of ethereal beauty and innate elegance who captivated countless famous admirers. Hailed as the "most beautiful woman and most faithful wife," she became a legend in Palermo. Kaiser Wilhelm II called her "The Star of Italy," while Gabriele D’Annunzio christened her "The One."

Everything about her was known: the infamous necklace symbolizing betrayal, her passion for horse racing, her friendships with D’Annunzio and the Kaiser, her travels across European capitals, her appearances at grand events, and her exorbitantly expensive gowns and jewels—so lavish they could outshine a queen. Franca played a pivotal role in managing the family’s vast empire, which included banks, factories, shipyards, foundries, tuna fisheries, saltworks, wineries, and one of Europe’s largest merchant fleets. The Florios dreamed of giving Palermo—and Sicily—a European identity, and it was Franca who cultivated relationships with luminaries like Arturo Toscanini, Puccini, Leoncavallo, Caruso, Montesquieu, and painters such as Boldini and De Maria Bergler. She mingled with Italian aristocracy, including the Duke Cesarini Sforza and the King of Italy, and international figures like Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria, the Tsar of Russia, and the Rothschilds.

Ignazio and Donna Franca were famed for their opulence, hosting lavish receptions for their illustrious guests. She reigned as the star of glittering soirées, draped in sumptuous gowns and priceless jewels—gifts from Ignazio, perhaps to atone for his frequent infidelities.

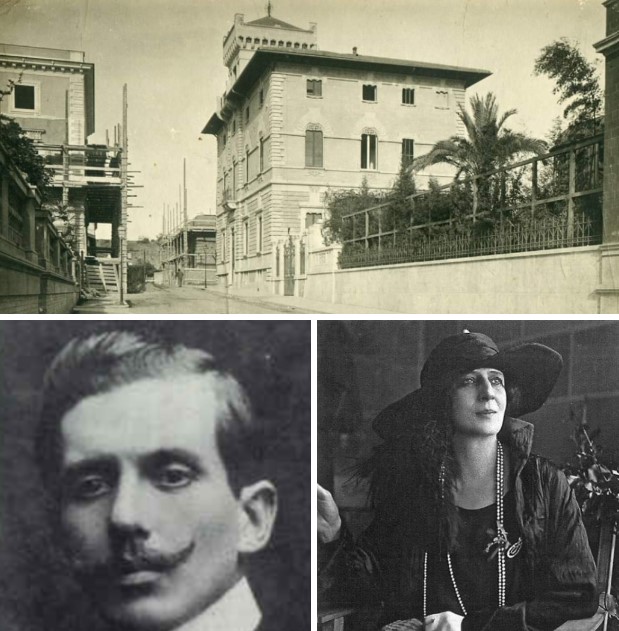

Ignazio Jr. commissioned two villas from architect Ernesto Basile, a master of Italian Liberty style and designer of Palermo’s Teatro Massimo. The first, built between 1899 and 1902 in Palermo, is one of Italy’s earliest Art Nouveau landmarks and a European masterpiece. The second, constructed in 1902 in Rome, stands in the Ludovisi district, an enclave of elegant villas blending Neo-Medieval, Renaissance, and Liberty styles—architectural jewels for nobility, politicians, and industrial elites drawn to Rome as Italy’s new capital.

Florio Villa in Palermo

The Roman villa, with its Florentine Renaissance flair, became Ignazio’s retreat in his later years, where he monitored the maritime laws that would ultimately ruin his family. Franca likely only visited him there, preferring hotels to cohabitation.

The Florio Villa on Via Abruzzi in Rome – Franca and Ignazio Florio Jr. (1903).

Yet her husband’s betrayals were not her deepest sorrow. Tragedy struck with the deaths of their children: first Giovanna, at nine, from meningitis; then "Baby Boy" Ignazio, their only male heir, dead at five under mysterious circumstances; and finally Giacobina, who lived just an hour after her premature birth. Only their daughters, Igea and Giulia, remained—though in an era that dismissed women as unfit heirs, their survival offered little solace.

Ignazio Florio Jr., Franca Florio and their first children Giovanna (1893-1902) and Ignazio "baby boy" (1898-1903), before 1903

Ignazio Jr., the sole sibling to uphold his father’s legacy, expanded the family’s ventures into shipyards, sulfur mines, and the grand Villa Egea—a sanatorium turned luxury hotel. But the political and economic climate turned against him. Post-Unification Sicily, the upheavals of World War I, crippling taxes, bank failures, and labor strikes eroded the Florio empire.

The Sicilian saga of the Florios spanned four generations and 130 years before collapsing in the 1920s and ’30s. Extravagance and financial mismanagement forced the liquidation of their assets—Franca’s jewels auctioned, their estates sold off. They ended their days as guests in their daughters’ homes, stripped of everything. Ignazio, deaf and broken, refused to see Franca on her deathbed. After her passing, he returned to Palermo, where he died in 1957.

The Palermo villa fell into disrepair until a 1962 fire gutted its interior. Restored decades later, it now welcomes visitors—a monument to a vanished world.

While, the Roman villa serves as the headquarters of a leading global strategy consultancy, advising corporations, governments, and nonprofit organizations worldwide today.

Rome, Via Abruzzi, 2/4