Power and passion of the Duchesses at the Savoy Court.

Turin, Italy

They were the principal ornaments of the court of Henry IV of France: the three beautiful young daughters born to him and his second wife, Marie de' Medici. Though still very young, they were already sought in marriage by various princes. But princely marriages are always arranged without investigating the will of the spouses. Politics advises them, guides them, confirms them. Hence often comes the misfortune of two beings, with differing aspirations, joined so indissolubly.

Marie Christine de Bourbon-France (1606-1663) was the third-born. From her mother, she inherited a thirst for command, an inclination for diplomatic intrigues, and that overpowering instinct for beauty and grandeur in art—which Marie had brought with her from Florence, the artistic city par excellence. From her father, she inherited some facial features, of which she was very proud, along with manly courage and vivacity of manner.

Not yet twelve years old, she was promised in marriage to Victor Amadeus, Prince of Piedmont, the eldest son of Charles Emmanuel I, to cement a Franco-Savoyard alliance against Spain. The marriage was celebrated privately in 1619 at the Louvre. She was 13 years old when she moved to the Savoy court in Turin, where she took the title of Madame Royale.

Turin in XVII century by Seutter

Given her young age and the difficult international situation of the Duke of Savoy in those years, her influence at court was negligible. Painstakingly, she managed to inaugurate the season of court ballets in Turin, following the Parisian example, even involving her husband in her amusements. She also established the fashion of dressing à la française —a political choice that replaced the Spanish style of dress favored during her in-laws' era. As she matured into womanhood, merely excelling at court or directing entertainments and pastimes was no longer enough for her. Her aspirations grew higher, surpassing even the bounds of art, to reach the point of meddling in political affairs.

Only after the death of her father-in-law in 1630 and her husband's succession to the throne did her position change significantly. From then on, Christine encountered no further obstacles to her most ardent ambitions. It was precisely in those years that the young duchess gave her husband their first children. They had six children in total: two sons and four daughters, including twins, one of whom lived only a few days.

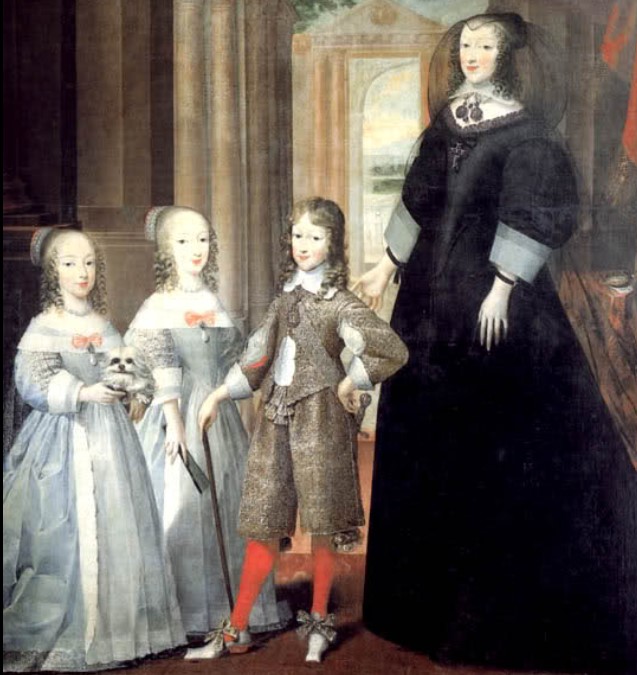

The Dowager Duchess of Savoy (Christine of France) with her children: Carlo Emanuele, Margherita Violante and Enrichetta Adelaide.

In 1637, she lost her husband: Marshal Créqui, commander of the French troops, held a banquet after which a council of ministers was to be held. Victor Amadeus, one of his ministers, and a general attended. Upon leaving the dinner, all three were seized by severe intestinal pains. The minister died after four days; the sturdier general recovered; while Victor Amadeus lingered. When his condition worsened, his wife was notified. Although convalescing from a minor illness herself, she rushed to him and found her husband in a bad state. From that moment, the illness rapidly worsened and soon threatened his life. Thoughts then turned to a will naming Christine as Regent. This will was promptly obtained, although some contested its validity, arguing it lacked the principal requirement: the testator's clear will.

Victor Amadeus died so suddenly and mysteriously that suspicion arose of Richelieu's hand behind it. It was the general opinion that Victor Amadeus I's will, concerning the Regency entrusted to his wife, was more interpreted by the onlookers—mostly French and all with vested interests—than expressly stated by him; and that the "yes" he uttered in response to the question was merely the sigh of a dying man

Victor Amadeus I

A year later, the widow lost her young Duke, Francis Hyacinth (1631), at only 9 years old: he had been frail since birth, suffering for a long time, and succumbed to asthma. The sole remaining heir was his little brother, Charles Emmanuel (1634), aged four. Her grief, her anguish, were immense; still in mourning for her husband, she doubled her widow's weeds and withdrew for several days to the Carmelite convent to weep freely and without witnesses.

A very beautiful and sensual woman, fond of festivities and balls, she was at the center of court gossip which attributed various romantic affairs to her. Marie Christine became regent first in the name of her son Francis Hyacinth and subsequently for Charles Emmanuel, who in 1648, at the age of 14, would ascend the throne as Charles Emmanuel II of Savoy.

When Duchess Marie Christine saw it was impossible to delay her son Charles Emmanuel's marriage any longer, she proposed to him, among many girls, her young cousin: Princess Marie Jeanne Baptiste of Savoy-Nemours (1644-1724). She was the great-granddaughter of Henry IV and cousin of Louis XIV (the Sun King), living in France at the court of Queen Anne of Austria. Since he had only seen her in a portrait, the Duchess thought it wise to facilitate the marriage by inviting mother and daughter to Turin, dedicating splendid festivities to them. At the sight of the girl, Charles Emmanuel showed considerable interest in her as a potential wife.

Portraits of the young Maria Giovanna Battista of Savoy-Nemours and cardinal Jules Mazarin (c. 1660) by Pierre Mignard I (1612–1695)

But the shrewd Cardinal Mazarin (1602-1661, Richelieu's successor), who did not wish to give up hope of placing his niece on the Savoy throne despite the harsh rebuffs encountered, whispered into Marie Christine's ear—knowing her weakness—that the young woman was of an imperious and haughty disposition, incapable of any submission. Thus, he managed to turn the Duchess against her. Abandoning all thought of marriage, she let the two princesses depart, showering them with kindnesses but without uttering a single word alluding to what they already knew was to be discussed during their stay.

If this displeased them, Charles Emmanuel was downright indignant. Annoyed, he wrote on a wall of the Castle of Rivoli:

La raison ne veut pas que je épouse M.lle de Nemours, mais mon destin le veut.

Reason does not want me to marry Mademoiselle de Nemours, but my destiny wills it.

And when later the Duchess spoke to her son about another marriage, he angrily replied that he wanted to choose his wife himself.

Mademoiselle de Nemours returned to France and nonetheless attracted the attention of Charles of Lorraine, heir to Duke Nicholas Francis of Lorraine. The court of Portugal had already requested her hand, but she had refused, preferring an engagement to Charles, which, however, was short-lived. That passion had to be sacrificed for reasons of State. She thus retired to the Convent of the Visitation.

Françoise Madeleine d'Orléans (Duchess of Savoy) in Ducal regalia by an unknown artist

But later, in 1663, Charles Emmanuel yielded to his mother's advice and married his cousin Françoise Madeleine d'Orléans (1648-1664), a descendant in the male line of King Henry IV of France. This time, the marriage was approved by Cardinal Mazarin. Marie Christine had chosen her specifically to maintain the power and influence over the government she had previously held as regent for her son since 1637.

Françoise Madeleine was so beautiful, good, and gentle that she was called the 'little dove of love'. She was so moderate in her desires that her mother-in-law truly had nothing to fear for her own sovereignty. Her daughter-in-law gave her every satisfaction: she shared every pleasure with her son, even following him on hunts to please him.

In Turin, less than a year after the marriage, Marie Christine died. Two weeks later, her daughter-in-law Françoise Madeleine also died without having given her husband any descendants.

Now a widower, Charles Emmanuel turned his thoughts once more to his cousin Marie Jeanne Baptiste of Savoy-Nemours. Since this time there was no one to oppose it, as soon as the year of mourning had passed, he formally asked for her hand.

The Duke of Savoy sent an ambassador to Paris, who also personally visited the princess in the convent where she had retired some time before. Informed of her cousin's widowhood, she candidly told the envoy that from that moment she had lost sleep and appetite and lived in great agitation, and that only then did she hope to regain her calm.

They married in 1665 in Turin at the 'Castello del Valentino'—a wedding gift his mother Marie Christine had received and where she loved to reside for long periods. The marriage was celebrated with a grand ceremony, the usual splendid festivities, and many guests.

Despite their passionate relationship and their only son, Victor Amadeus, the Duke had numerous mistresses and just as many illegitimate children, which Marie Jeanne Baptiste was forced to ignore from the earliest months of the marriage. The husband, unfaithful to his wife, wrote to a friend:

I make a great number of people jealous, and I enjoy deceiving right and left, and sometimes making my wife angry, but she has already begun to become more reasonable.

And indeed, Jeanne showed herself as reasonable as he said, only so as not to reveal to others all the pain and displeasure she felt.

Portrait of Carlo Emanuele II and his wife Maria Giovanna Battista of Savoy and their son Vittorio Amedeo in 1666 by Charles Dauphin and 'Castello del Valentino'

Charles Emmanuel had an immense, almost excessive tenderness for his son, and this, like most excesses, proved fatal to him. Victor Amadeus was a very lively child who often rode horseback under his father's watchful eye. One day, the Duke was so frightened upon seeing the little prince fall from the saddle that, from the shock, he was struck by chills and then by a convulsive fever. He deteriorated rapidly because he neglected the fever. Feeling death approach, he ordered the palace doors opened so that his people, who had seen him live, might see him expire. He had already made a will, entrusting the guardianship of his nine-year-old son and the Regency to his wife, who did not have the strength to assist him in his final moments.

Marie Jeanne Baptiste, called Madame Royale like her mother-in-law, made a grave mistake for which she later paid dearly: she cared little for her son and his education. Every day, at a certain hour, his governor, the Count of Monasterol, brought the boy to his mother. He would kiss her hand according to all the rules of etiquette, listen to her observations and complaints, and then return to his rooms; and these were all the interactions that existed between them. Very different in this from his father, who had cultivated domestic affections, Victor Amadeus felt nothing but fear for his mother and yearned only for the day he could free himself from her subjection and spread his wings.

So-called portrait of Victor Amadeus II of Savoy (1666-1732) and his wife Anne Marie d'Orléans (1669-1728).

Christine of France and Marie Jeanne Baptiste of Savoy-Nemours were two women who drove significant development in the society and artistic culture of the Savoy state, striving to make Turin an international city on par with Madrid, Paris, and Vienna. They were two emblematic figures of European history, who exercised their power in a distinctly feminine way to affirm and defend their own role and the autonomy of their State.

Marie Christine assumed the regency for her underage son Charles Emmanuel and clashed with her brothers-in-law, the Princes, who were supporters of the Spanish. Nevertheless, she succeeded in maintaining the Duchy's independence and her own power, which she formally ceded to her son in 1648 but effectively continued to wield until her death. In her later years, Christine underwent a religious conversion that transformed her radically, "...bringing to affliction the same taste for excess she had had in pleasure": she practiced extreme penances and frequented the convent of the Discalced Carmelites, which she herself had brought to Turin. At her death, she was buried dressed as a Discalced Carmelite.

In contrast, Marie Jeanne Baptiste of Savoy-Nemours was a woman of cold, authoritarian character, animated by great ambitions. During her regency, she organized magnificent and costly festivities for the Savoy court and was consequently accused of squandering and abusing the royal treasury. But Jeanne's plans were perhaps to distract her son's attention from politics by organizing carefree palace parties for him. Moreover, the Queen Regent enjoyed amusing herself with numerous noblemen of the court, so much so that she was often considered by the people as overly libertine.

Initially, she decided to assume the regency of the Duchy of Savoy until her son Victor Amadeus II reached his majority (age 14). However, when the time came in 1680, her desire for power did not cease. She thus sought to marry her son to his cousin, Isabel Luísa of Braganza, daughter of King Peter II of Portugal and her sister Marie Françoise of Savoy-Nemours, hoping to make him king in Lisbon. If her son moved to Portugal, Jeanne Baptiste could have governed Piedmont for much longer. But Victor Amadeus II, intuiting his mother's plan and urged by his ministers, staged a sort of coup d'état, declaring her deposed and stripped of all political authority. Jeanne was forced to bow to her son's will.

Advised to be gentler with her son, the Duchess had tried in vain with a thousand little attentions. She celebrated his coming-of-age birthday with greater pomp and splendor than usual, but he was never moved by appearances. Thus, sidelined from politics, Marie Jeanne Baptiste decided to dedicate herself to art and the urban beautification of Turin. Generally, however, Jeanne was not liked by her subjects or relatives; only her daughter-in-law and granddaughters were exceptions. It was among them that she later led a retired and tranquil life, outliving both of her favorites and living to eighty years old.

Viale Pier Andrea Mattioli, 39 (Turin)