Discovering the Tomb of the Legendary Cretan King Minos

Alia (Palermo), Italy

In the 3rd–2nd millennium BCE, autonomous political and social systems began to emerge in Anatolia and the Greek world. Among these, the most significant arose on the island of Crete, where the magnificent Minoan civilization flourished. Crete became a cultural crossroads and a wealthy maritime power that dominated the Aegean Sea until the arrival of the mainland Mycenaeans around 1400 BCE.

The Minoan civilization takes its name from the legendary King Minos, son of the union between Zeus and the Phoenician princess Europa. The figure of Minos, straddling myth and history, reflects the splendor of this civilization.

The Legend of Minos

Minos was the ruler of Knossos, Phaistos, and Kydonia (the three ancient metropolises of central, southern, and northern Crete), who received dominion over the sea from Poseidon. Not only was he a king, but also a priest and lawgiver, renowned for his justice.

The legend tells that Europa, after arriving on the island on the back of Zeus (who had transformed into a bull), married Asterius (or Asterion), the local king who adopted Minos and the other children she had with the god. Upon his father’s death, Minos claimed the throne. Concerned that his people saw him as illegitimate, he asked the sea god Poseidon to send him a bull from the waves as a sign of divine approval for his reign. A magnificent white bull emerged, which Minos was supposed to sacrifice. But when the time came, enchanted by the animal’s beauty, he spared it.

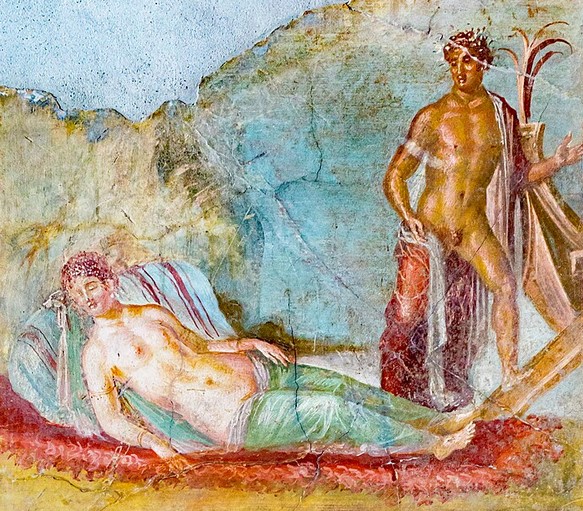

Fresco discovered in the House of the Vettii in Pompeii, depicting Daedalus showing Queen Pasiphaë the wooden cow that would allow her to unite with Poseidon’s beautiful bull—the object of her desire.

According to some versions of the myth, the king decided to use it as a stud bull for his herds. When Poseidon discovered the deception, he was enraged and resolved to punish him. Thus, he made the king's wife, Pasiphaë, fall in love with the bull.

Consumed by her desire for the sacred bull, Pasiphaë begged the Athenian architect Daedalus for help. He crafted a wooden cow for her, inside which the queen awaited the breeding. She later gave birth to Asterius, who became known as the Minotaur.

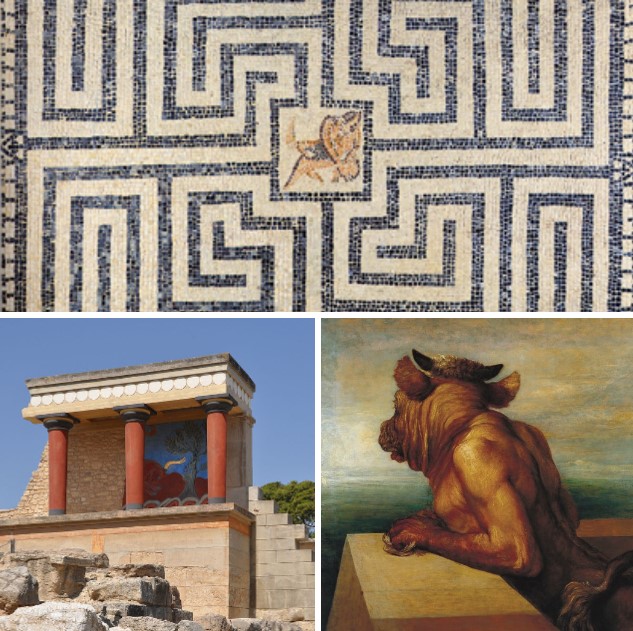

1) Mosaic from the Domus del Labirinto in Calvatore (Cremona, Italy), now housed at the Museo Platina in Piadena. It depicts the labyrinth of the Minotaur. The Minotaur's labyrinth symbolizes mankind's journey through earthly struggles, from life to death, while the center of the maze is a sacred space representing rebirth and human knowledge.

2) The Palace of Knossos.

3) An oil painting by George Frederic Watts portraying the Minotaur, 1885 – Tate Modern, London. The mythical creature became a symbol of rapacious lust and greed in modern civilization.

The Minotaur was a monstrous creature, half bull and half man. Despite having human legs, its animal nature made it wild and dangerous to the citizens. Horrified by its appearance, Minos tasked the architect Daedalus with building a palace from which escape would be impossible—a place to imprison the Minotaur. Daedalus constructed the Palace of Knossos for the king, a vast labyrinth made up of chambers, corridors, fake entrances, and false exits.

When the Athenians killed Androgeus, one of Minos' sons, the Cretan ruler imposed a tribute on Aegeus, the king of Athens: the sacrifice of seven young men and seven young maidens to be fed to the Minotaur every nine years, in order to appease it.

In this Pompeian fresco, one of the young freed Athenians expresses his gratitude to Theseus, who stands at the center of the scene. The Minotaur lies dead in a corner. National Archaeological Museum, Naples. The battle between Theseus and the Minotaur symbolizes the eternal struggle between good and evil.

Theseus, son of Aegeus, decided to free Athens from the tribute of human sacrifices by killing the Minotaur. So he volunteered to be among the sacrificial youths. He arrived in Crete with the young men and maidens destined to be the monster’s victims.

Ariadne, daughter of the cunning Minos and Pasiphaë, fell in love with him. Before the young man entered the labyrinth, she gave him a ball of thread, which he was to unwind as he went inside so he could find his way back after slaying the Minotaur. Theseus ventured into the winding maze, weapon in one hand and the thread in the other. In the darkness, he caught sight of the monster’s shadow. He lunged at it and killed it, then freed the thirteen other youths meant for the Minotaur’s jaws. Together, they rushed toward the exit where Ariadne awaited them. Once free, they destroyed the enemy fleet and set sail for Athens.

Ariadne sleeping on the coast of Naxos; Theseus boarding his ship - period / date: fourth style of pompeian wall painting - findspot: Pompeii, VII, 4, 31-51, house of the coloured capitals / house of Arianna - museum / inventory number: Napoli, Museo Archeologico Nazionale 9052

After a stop at Delos, the youths landed on the island of Naxos (Dia), where the two betrothed lovers consummated their love, and the deception took shape. Theseus, in truth, did not love Ariadne and had no intention of marrying her (Plut. Thes. 19; Hygin. Fab. 42; Didym. ad Odyss. xi. 320)—above all, he feared possible retaliation from Minos. When the maiden fell asleep, he set sail with his ship, abandoning her. Here, depending on the version, the forsaken girl either hanged herself or began weeping until she was comforted and abducted by Dionysus. Possessed by the god, she was then killed by Artemis (Hom. Od. xi. 324)—daughter of Zeus and Leto and twin sister of Apollo—for having lost her virginity, or else she became the god’s bride, and he granted her the gift of immortality.

In any case, Poseidon, enraged at Theseus for abandoning the girl, summoned a storm that tore the white sails of Theseus’ ship, forcing the young man to hoist black sails instead.

Before Theseus had departed, King Aegeus had asked his son to raise black sails only in case of defeat. When Aegeus saw a ship approaching with black sails, he decided to take his own life by throwing himself into the sea. From that moment on, the sea bore his name: the Aegean Sea.

Roman fresco depicting the Fall of Icarus, discovered in Pompeii, now housed in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples (inv. 9506).

Minos imprisoned Daedalus and his son Icarus for helping Theseus escape the labyrinth. To evade the king’s wrath, they fled, soaring far from the island of Crete. Their journey, however, ended in tragedy: during the flight, Icarus flew too close to the sun, melting the wax of his wings and plunging into the sea to his death. Meanwhile, Daedalus was forced to change his course and take refuge in Sicily. There, he was welcomed with great honor by Kokalos—king of the local Sican people—so much so that he felt compelled to repay the hospitality by designing and constructing legendary works, including the mythical (and now lost) stronghold of Camīcus.

The ancient Sican city of Camīcus has never been located. We know it had already lost its significance by the 6th century BC and that its fortress fell with the decline of Agrigento during the First Punic War and later under Roman rule.

Today, two main sites—both situated on rocky outcrops—contend for its location. The first lies near the village of Sant’Angelo Muxaro, northwest of Agrigento; the second atop Mount Guastanella, close to the town of Saint Elizabeth, where the ruins of an ancient fortress—possibly the one described by Diodorus Siculus—can still be seen.

Location of the Gurfa Caves (Palermo) and Camicus

According to Herodotus, Diodorus Siculus, Aristotle, Strabo, and other ancient sources, when Daedalus fled to Sicily, Minos decided to pursue him to capture him. Welcomed at the palace of the Sicanian king Kokalos in the ancient Sicanian city of Camicus, Minos was treacherously killed in a bathtub by the daughters of his host monarch.

But the infatuated Icarus, disregarding his father's injunctions, soared ever higher, till, the glue melting, he fell into the sea called after him Icarian, and perished. But Daedalus made his way safely to Camicus in Sicily.

And Minos pursued Daedalus, and in every country that he searched he carried a spiral shell and promised to give a great reward to him who should pass a thread through the shell, believing that by that means he should discover Daedalus. And having come to Camicus in Sicily, to the court of Kokalos, with whom Daedalus was concealed, he showed the spiral shell. Kokalos took it, and promised to thread it, and gave it to Daedalus ...

- Library (epitome) by Apollodorus, e.1.14 - ca. 100 CE

In Book VII of his work, Herodotus recounts that the city of Camicus was besieged by the Cretans, who had come from their island to avenge Minos' death. After five years of war, the Cretans, unable to conquer the city, abandoned the battlefield.

Indeed, it is said that Minos, having come to Sicania [now called Sicily] in search of Daedalus, met a violent death there. Some time later, urged by a god, all the Cretans—except those from Polichne and Presos—sailed in a great fleet to Sicania and laid siege to the city of Camīcus (which in my time was inhabited by Agrigentines) for five years. In the end, however, unable to capture it and no longer able to endure the hardships of famine, they abandoned their camp and departed.

After Minos' death, his bones were handed over to the Cretans who had followed him to Sicily, and they built his tomb in the territory of what would later become the Greek polis of Akragas (modern-day Agrigento). He was buried in a monumental funerary complex dedicated to the goddess Aphrodite, located near Camicus along the valley of the Halycus/Platani River.

Several ancient sources recount how the tomb was later destroyed by Theron, the tyrant of Agrigento, in 480 BC. While marching up the Platani River to wage war against Himera, Theron rediscovered the tomb—nearly a millennium after its construction.

Thereupon the comrades of Minos buried the body of the king with magnificent ceremonies, and constructing a tomb of two storeys, in the part of it which was hidden underground they placed the bones, and in that which lay open to gaze they made a shrine of Aphrodite. Here Minos received honours over many generations, the inhabitants of the region offering sacrifices there in the belief that the shrine was Aphrodite's; but in more recent times, after the city of the Acragantini had been founded and it became known that the bones had been placed there, it came to pass that the tomb was dismantled and the bones were given back to the Cretans, this being done when Theron was lord over the people of Acragas.

- Bibliotheca historica by Diodorus Siculus, 1-7, 4.79.3 - ca. 49 BCE

Minos' death at the hands of Kokalos' daughters suggests that Daedalus, to conceal the king’s tragic demise, constructed a grand temple-tomb to demonstrate to the Cretan army that King Kokalos and he held great respect for the Cretan king and that his death had been accidental.

Gurfa Caves

Gurfa Caves

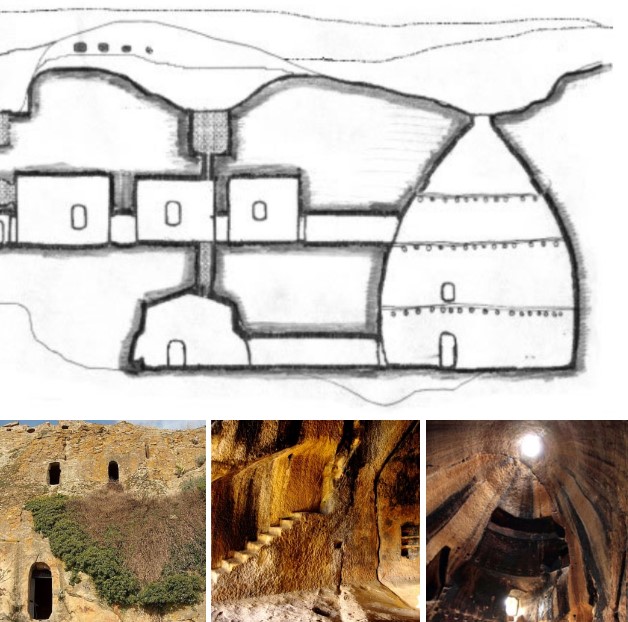

Some scholars believe that the Gurfa Caves may have temporarily served as the tomb-temple of Minos. Located five kilometers from Alia, a town of Arab origin in the province of Palermo, they constitute an ancient rock-hewn settlement dating back to the Bronze Age (between 2500 BC and 1600 BC)—a kind of "prehistoric sanctuary" carved into solid rock.

The architect of this grand structure appears to have drawn inspiration from the models of houses and thòlos tombs (funerary constructions) found in the Cypriot site of Choirokotia, as well as the Anatolian-Phrygian wooden Megaron of Gordion. Thòlos monuments were built in Egypt, Greece (by the Mycenaean civilization), and in Portugal and southern Spain (by the Los Millares culture and the later El Argar civilization). However, the thòlos tomb of the Gurfa Caves (which are not actually caves) is the largest in the Mediterranean—bigger and older than the Treasury of Atreus in Mycenae, predating even the collapse of the Minoan-Mycenaean civilization, which occurred with the eruption of Santorini in 1603 BC.

The Minoan civilization had a presence in Sicily. This island has always been shrouded in myths and legends, some of which may hold a grain of truth. Although not all scholars believe that the mythological figure of Minos actually existed, an ancient Sicilian narrative claims to reveal his tomb, thereby supporting his historicity. Thus, the Gurfa tomb-temple must have been built for a great king like Minos. Supporting this theory is an inscription depicting a trident—the symbol of Poseidon, the sea deity at the pinnacle of the Minoan-Mycenaean pantheon, who sent the sacred bull as a gift to the Cretan king.

The trident—the symbol of Poseidon.

The Gurfa Caves consist of a magnificent bell-shaped chamber (tholos) measuring 10 meters in width and 16 meters in height, pierced at the top by an opening that lets in light (much like the Pantheon in Rome), and a large tent-like room on the ground floor. These spaces are connected by corridors, staircases, cisterns, a descent well, passageways, and four upper-level rooms, along with several other small chambers likely intended for funerary purposes at the top of the slope.

The Gurfa Caves - In the days around the summer solstice, at noon on June 21st, the sunlight creates a magical transfiguration effect on anyone standing beneath the blade of light. This phenomenon is also known as "hierophany," meaning a manifestation of the sacred in the history of religions.

During the Spring Equinox, a strange phenomenon occurs here—a blade of light, a striking beam from an oculus at the summit, illuminates the Nadir pit. This very opening is believed to be additional evidence of the connection between this monumental human creation and the Mycenaean world. In the ritual of Katabasis (descent into the underworld), the courage of the future king was tested by lowering him through an opening into a tomb, where he would remain for an unspecified period to prove his defiance of death. It was a kind of descent into Hades, followed by an ascent as a sovereign.

This grand temple was undoubtedly a major pilgrimage site, as evidenced by the purification basins outside the temple and the numerous inscriptions and graffiti on its outer walls. Nothing remains of the original wooden structure, as it was destroyed and burned by Theron. The traces of tar-like scorch marks along the walls of every chamber compel us to reinterpret history. Over time, the temple became a place of worship and contemplation—for the Greeks, who venerated Aphrodite, and for the Phoenicians, who worshipped Astarte. The presence of the latter is attested by the graffitied symbol Beth (House) on the right side near the temple’s entrance.

symbol Beth (House).

For millennia, the site remained a sacred area revered and contemplated by other religions, as evidenced by various carvings: the engraved trident points to Poseidon, the Paleo-Christian cross, and the medieval IHS symbol.

Archaeological investigations have also confirmed that this place was repurposed as an expanded grain storage pit during the late Roman or Byzantine era. It is no coincidence that the term Gurfa likely derives from the Arabic Ghorfa, which became Gurfi in Sicilian, meaning precisely "storage room," given that the Arabs used it for this purpose.

Alia (Palermo)

Email: ufficioturisticoalia@libero.it

Mount Guastanella

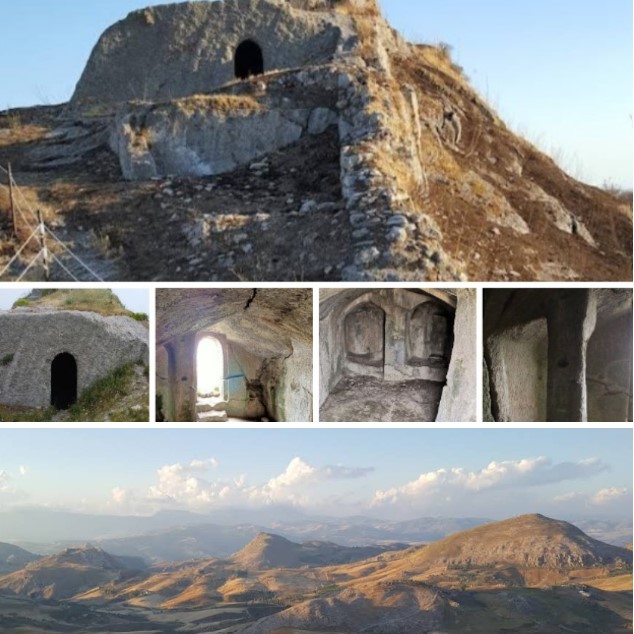

Dr. Rosamaria Rita Lombardo, after years of studying written and oral traditions—along with archaeological investigations on her family's land on Mount Guastanella (now a candidate UNESCO site)—may have identified the true burial place of the legendary Cretan king Minos.

This fascinating archaeological hypothesis is supported by both historical accounts of King Minos’ tragic demise in Sicily and evidence from on-site surveys, including topographic, toponymic, and hydrographic analyses. Additionally, the theory is reinforced by invaluable local folklore, which Dr. Lombardo has personally collected and verified.

Located about twenty kilometers from Agrigento’s Valley of the Temples, Mount Guastanella bears traces of ancient settlements—including a necropolis and an Arab castle—leading Dr. Lombardo to theorize that the summit once hosted the ancient city of Camīcus.

The mountain’s stratified layers suggest it was inhabited far earlier than previously believed and may conceal a sanctuary-tomb resembling those built in Crete—likely belonging to King Minos. Further supporting this claim are traces of heroic cult worship by local Sicilian Greeks, who historically revered Minos, as well as local folk tales. These include stories of "King Mini-Minos" buried on the mountain and even darker legends portraying him as a boogeyman-like figure used to frighten misbehaving children.

If future excavations confirm Dr. Lombardo’s theory, it would mean that contact between the Aegean world and Southern Italy occurred much earlier than currently assumed.

Monte Guastanella Burial Site and scenic overlook.