The Volscian Rostra of Antium: The Spurs Bronze Beaks that Adorned the Roman Forum

Rome, Italy

The ancient coastal Lazio was inhabited by peoples linked to seafaring, of Ligurian-Iberian origin. By coexisting and merging with Phoenician and Greek lineages who penetrated the region in the 3rd–2nd millennium BC, they gave rise to the various Latin ethnicities. These peoples engaged in intense maritime activity from the most ancient times. These early peoples shared a common cultural base but had distinct peculiarities determined by the different resources of the territories they inhabited.

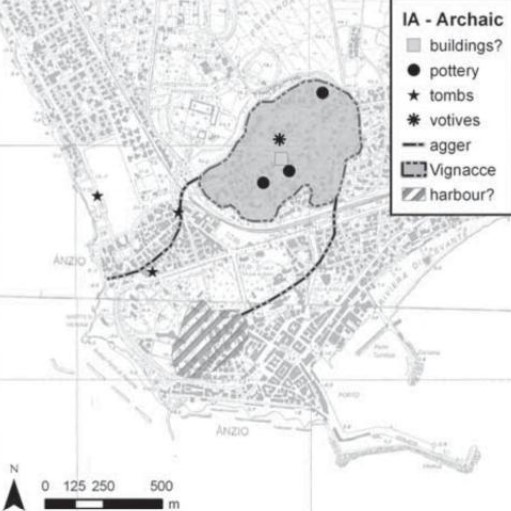

The earliest forms of settlement in the territory of Antium (Anzio) date back to the Bronze Age, continuing without interruption until the beginning of the 3rd century AD. The Colle delle Vignacce (Santa Teresa locality) was a settlement site for Latin peoples, then the Volsci, and subsequently the Romans.

On this natural plateau, the first settlements were present. They were scattered and not unified into a single village, and the settlement was not yet fortified.

Proto-historic and Archaic remains at Antium

The settlement was enclosed by a defensive vallum (Latin-Volscian Rampart) in the 9th century BC – according to carbon-14 dating of the agger's foundations – when the need arose to defend the entire plateau, which was by then fully inhabited.

In the following two centuries, the vallum was extended southwest towards the sea. All necropolises were located outside it except one, which might mean it was built before the extension of the agger towards the sea when that area was uninhabited.

The presence of necropolises and defenses suggests the site was an important central settlement during the Iron Age. Indeed, we know that around the 9th century BC, the Latins founded Antium. According to the historian Xenagoras, located about fifty kilometers from Rome, it was founded by Anteias, son of Ulysses and the sorceress Circe; while another legend attributes it to Ascanius, son of Aeneas, already the founder of Alba Longa. Thus, Antium was a city older than Rome.

Indicative area of the 2021 archaeological excavations in Via del Teatro Romano, Anzio.

In the 7th century BC, the agger was reinforced with a wall, and its extension reached the edge of the sea. This would testify that the settlement area had more than doubled, extending beyond the Vignacce plateau. A port most likely existed, but we cannot confirm this as its remains have never been found. Archaic burials (7th and 5th centuries BC) date back to this period, with skeletons and grave goods, attributable to the Volsci. They were uncovered during excavations less than 200 meters from the Roman Theatre of Antium at a depth of about two meters. Five burials were found, three of which related to individuals in primary deposition and with different orientations.

Tomb 2, burial site in Via del Teatro Romano, Anzio (6th century BC).

Specifically, Tomb 2, an earthen pit, contained an individual in primary deposition, male, over fifty years old, in a very poor state of preservation. The burial had a southeast/northwest orientation, and the grave goods suggest a dating around the 6th century BC. The individual exhibited a non-physiological curvature of the spine at the cervical and thoracic vertebrae, and a series of markers at both dental and bone levels, suggesting poor health or bone degeneration related to old age.

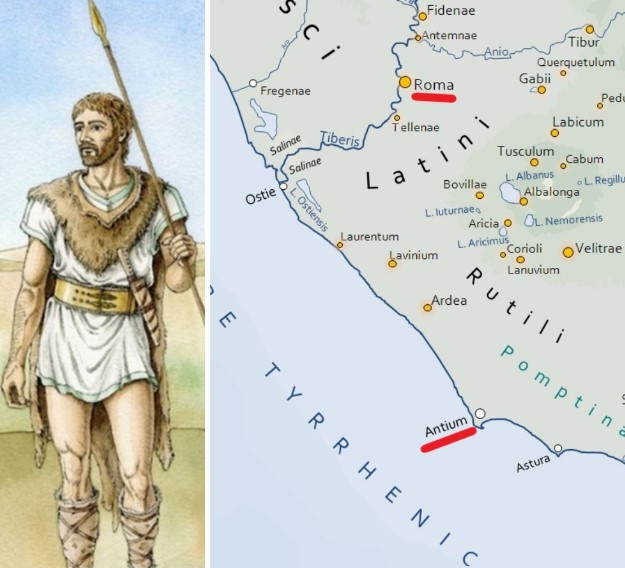

Map of ancient Latium showing Antium and Rome, with a graphic reconstruction of a Volscian warrior

The Volsci were an Oscan-Umbrian people originating from northern Campania, who in the 5th century BC (493 BC) occupied part of the Latin territories along a front stretching between Velitrae (Velletri), Satricum, and Antium.

Antium became their principal and most powerful city. It was particularly opposed by the Romans, who desired to seize its port, located only 58 km from Rome, thus partially compensating for the difficulties of the Tiber estuary, not always usable for cargo ships.

The Volscian economy was centered on navigation and piracy practiced as far as the Aegean Sea. Titus Livy, who did not hold a high opinion of the Volsci, defined them as:

a people more warlike in rebellion than in waging war.

The ancient Volscian city was located inland from the modern one, somewhat distant from the sea, on the Vignacce plateau surrounded by the vallum which formed its fortification. It had a perimeter of 3,900 meters and the shape of an irregular trapezoid. It was situated a short distance from the sea and was probably equipped with walls. No traces of access gates remain, but there must have been at least three: one in the direction of Rome, where the Via Anziatina entered, joined with the Via Severiana; one towards the sea; and one towards the Astura River.

Locations of the Latin-Volscian Rampart at Anzio and the presumed ones of the Caenon

Antium controlled a fortified stronghold, known as Caenon, which served as its port and emporium from which the Anziati launched their pirate raids. For defensive reasons, the port area remained outside the walls. The location of the port is still unknown: some sources place it on the coast of Capo d'Anzio, where Nero's port later arose; other sources place it near the mouth of the Loricina River, where the medieval castle of Nettuno now stands; others at the mouth of the small Sant'Anastasio River; and finally, archaeological excavations conducted since the 1960s place it north of the ancient city, about 13 km away.

Conflicts between the Volsci and the Romans, beginning as early as the end of the 6th century BC, characterized the city's history in subsequent centuries. After numerous clashes, the Romans managed to found a Latin colony at Antium in 467 BC. Until the second half of the 4th century BC, the Romans had only a few warships, strictly proportionate to the need to protect the riskiest stretches of the maritime routes leading to Ostia to ensure the flow of supplies essential for Rome's survival. But when, in 340 BC, the territories of the Lazio coast, from Ardea to Ostia, were subjected to raids by the Volsci of Antium, who possessed a powerful military fleet, it became evident that Rome had to strengthen its control over the sea as soon as possible.

Though defeated by Rome multiple times, Antium always found occasion to rebel and take up arms again, until in 338 BC, the Romans, thanks to the Battle of the Astura River, definitively subdued it. They occupied it and destroyed Caenon (the port stronghold), so from that moment the city remained without a port system at least until the age of Augustus.

The Volscian fleet was partly destroyed and partly captured by the Romans: the serviceable ships were transferred to Rome and placed in the Navalia (protected slipways used by the military fleet as a naval base and arsenal), while the older and more dilapidated ones were burned after removing the rostra (bronze rams) from their prows.

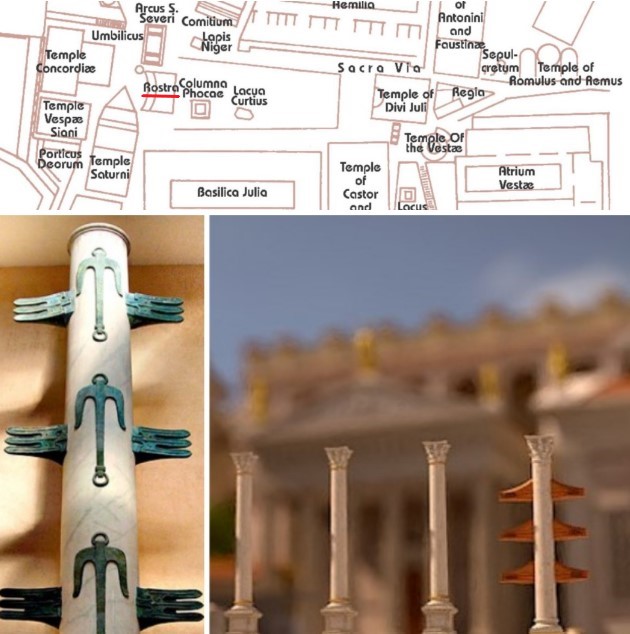

Locations of the Latin-Volscian Wall in Anzio and the presumed sites of the Caenon. Map of the Roman Forum highlighting the location of the Rostra; reconstruction of an ancient rostrate column (Rome, Museum of Roman Civilization) and graphic reconstruction of the Rostra Augusti

These sturdy bronze rams were also brought to Rome as spoils of triumph. After the Gallic sack of 390 BC, Rome rebuilt the Comitium for the first time, and the prows of the ships were affixed to the speaker's platform as trophies, which from then on assumed the name Rostra. They, by the will of Caesar, were moved here from the nearby Comitium (meeting place), and later enlarged by Augustus. They were a platform (height about 3 meters, length 24 meters, width 12 meters) reachable by a staircase on the side towards the Capitoline Hill, supported by a wall of tufa blocks faced with marble slabs. The holes that held the rostra are visible. Monuments and honorific columns rose on the platform and behind it (they are depicted in reliefs), while the parapet was perhaps adorned with the so-called Plutei of Trajan.

Sculpted frieze on the Arch of Constantine depicting the emperor addressing the army and showing the Rostra.

The Rostra, which at the time were arranged opposite the Senate Curia, at the boundary between the Comitium area and the Roman Forum square, were enlarged precisely on that occasion. The same structure underwent another renovation around 263 BC, acquiring a circular arc shape, concentric with the new circular plan of the Comitium; this is also seen on the reverse of a silver denarius of 45 BC, minted by Lucius Lollius Palicanus, where three of the rostra fixed to the pillars of the frontal arches of the tribune are clearly recognizable, viewed from the Forum.

Coin die of Lucius Lollius Palicanus—likely honoring his father Marcus—depicting the rostra.

The historic tribune was finally rearranged by Caesar and Augustus on the center of the western side of the Forum square, where we still see it today. The ancient Anziate naval rostra therefore maintained this location throughout the duration of the Empire, eventually being flanked by other rostra eight centuries younger: those from the Vandal ships captured during the last naval victory achieved by the Romans, in the second half of the 5th century.

The jealous preservation of the oldest naval trophies and their ostentation in the heart of the Urbs for over eight centuries show the exceptional importance attributed by the Romans to the capture of the ships of Antium, even though all subsequent Roman history was studded with naval exploits far more glorious and qualifying. Yet even Pliny the Elder, who commanded the Misenum fleet, the most powerful of the Roman imperial fleets, confirmed the importance of the success achieved over the small Anziate fleet, writing that:

The rostra of the ships, fixed in front of the Rostra, adorned the Forum like a crown conferred upon the Roman People themselves.

The Rostra

In 338 BC, a Roman colony was also established in the Latin city, governed directly by magistrates sent from Rome, and the Anziati were forbidden to use the sea.

Thus ends the history of Volscian Anzium, and begins that of Roman Anzium.

Rome, Roman Forum