The Clash of Titans: Pope Julius II, Michelangelo, and the Birth of a Masterpiece in the Sistine Chapel

Rome, Italy

Pope Julius II (Giuliano della Rovere, nephew of Pope Sixtus IV, 1503-1513) is considered one of the most celebrated pontiffs of the Renaissance. He was a patron of Michelangelo and Raphael, the initiator of the construction of the new St. Peter's Basilica, and the founder of the Vatican Museums and the Swiss Guard. His relationship with Michelangelo was tempestuous. Both possessed incredibly strong personalities and were unaccustomed to compromise.

Fresco by anonymous artist on the vault of the Sistine Hall, Vatican Palaces, Vatican Apostolic Library, Vatican City. It depicts St. Peter's Basilica in the 16th century

In 1505, Julius II summoned Michelangelo to Rome to entrust him with the task of creating a monumental tomb for himself, to be placed in the tribune of the new St. Peter's Basilica. Michelangelo presented the initial project and traveled to Carrara to select the marbles. However, in the meantime, the Pope had a change of mind, perhaps advised by the architect Bramante, who did not hide his rivalry with Michelangelo: the pontiff began to think that the idea of working on his own tomb while still alive was a bad omen. Thus, in the spring of 1506, Michelangelo, returning laden with marbles and expectations after exhausting months of work, made the bitter discovery that his colossal project was no longer the Pope's main interest, having been shelved in favor of the Basilica's construction and new military campaigns against Perugia and Bologna

On April 18, 1506, furious over the court intrigues, Michelangelo hastily left Rome, taking refuge in Florence for almost a year. The Pope, however, already had another grand project in mind for the artist but did not have time to communicate it to him; while it is true that the artist had a fiery temper, it is also true that the pontiff was immensely ambitious and loved art for its political function.

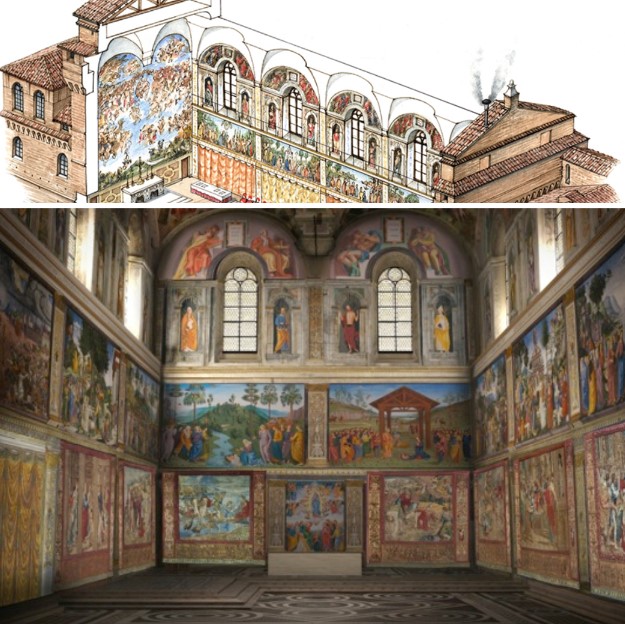

The Sistine Chapel today and before 1500

The reason for this new project was the need to eliminate a threatening crack in the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, which since May 1504 had prevented its use. Intervention was urgent because the Chapel hosted the most important and solemn celebrations of the papal court. Therefore, the vault, previously frescoed by Pier Matteo d'Amelia with a starry sky during the time of his relative and predecessor Sixtus IV, needed to be repainted.

On May 10, 1506, while in Florence, Michelangelo received a letter from the Florentine carpenter and master builder Piero di Jacopo Rosselli, who recounted a dinner held a few days earlier in the Apostolic Palace in Rome. On that occasion, Pope Julius II reportedly revealed to Bramante and other guests his intention to entrust Michelangelo with the repainting of the Sistine vault. However, the architect from Urbino (Bramante) responded by casting doubt on the Florentine's real abilities, given his lack of experience in fresco. Rosselli immediately leapt to the defense of his fellow Florentine, Michelangelo, later warning him and urging him to accept the commission.

The letter testifies to the actual existence of rivalries among the artists of the papal court, who, constantly vying for the Pope's favor, did not want to miss opportunities to enrich themselves by working on grandiose, competing projects, as the availability of funds, though immense, was not infinite.

The Pope believed in Michelangelo's artistic gifts. It took no less than three 'briefs' (papal documents less solemn than bulls) from Julius II sent to the Signoria of Florence and the continuous insistence of the Gonfaloniere Pier Soderini, who tried in every way to convince the great artist to consider the possibility of reconciliation, telling him, "We do not wish to go to war with the pope for your sake and put our state at risk." An irritated Michelangelo once stated that he was a sculptor and had no interest in painting what appeared to be the ceiling of a large barn.

Sistine Chapel ceiling

In 1507, an opportunity arose. It was provided by the Pope's presence in Bologna, engaged in the military campaign against the Bentivoglio family. There, Michelangelo cast a bronze statue for him, and a year later, in Rome, he finally obtained the reparative commission for the decoration of the Sistine Chapel vault.

Given his experience, the artist considered himself more of a sculptor than a painter, simply because he had not practiced the fresco technique for years. But this did not mean he could not be an excellent painter. Ambitious as he was, he decided to accept the task, recognizing it as an opportunity to demonstrate his ability to surpass limits, directly competing with the great Florentine masters under whom he had trained. This way, he could also clear himself of the accusations and controversies regarding the delays in creating Julius II's tomb.

The commission represented a monumental challenge for the artist, who completed the complex decoration of the nearly 550 m² vault in just four years.

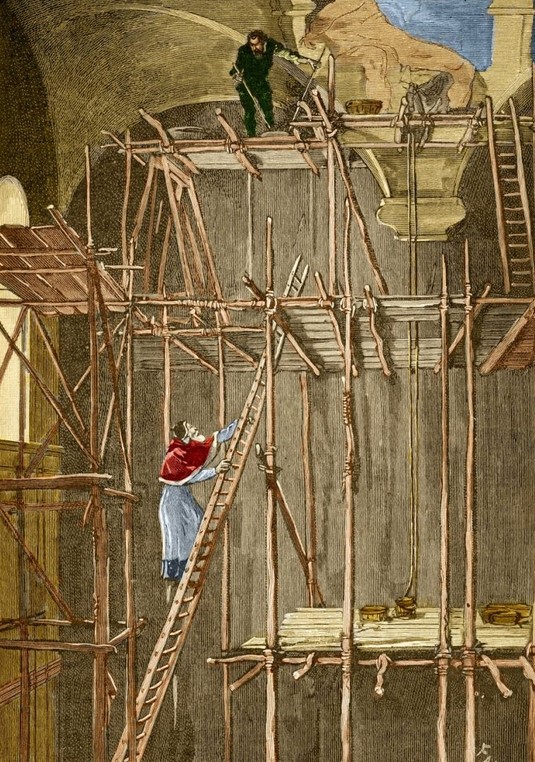

The assignment was formalized in Rome between March and April 1508. The first months were occupied with preparatory drawings (sketches and cartoons), the construction of the scaffolding, and the preparation of the surfaces to be frescoed, a task overseen by master Piero Rosselli.

To be able to reach the ceiling, Michelangelo needed scaffolding that would also allow religious and ceremonial activities to continue simultaneously in the chapel. The initial scaffolding designs were conceived by his rival Bramante, who designed a special structure suspended in the air by ropes. Michelangelo, who in his letters and in his biographers' writings never missed an opportunity to discredit and question the artistic abilities of his rivals (primarily Bramante and Raphael), judged the structure completely inadequate, as it would have left holes in the ceiling once the work was finished. He completely rebuilt the scaffolding himself.

The scaffolding on which Michelangelo worked occupied about half of the chapel. Beneath it, he had spread a huge canvas to avoid disrupting liturgical activities, to prevent soiling the floor, and, most importantly, to keep others from peeking at his work in progress.

He thus rebuilt the scaffolding himself, out of wood, covering half the chapel. Highly praised by Vasari, it was actually based on an adaptation of a system already in use for vault construction: six pairs of trusses supported a suspended, stepped scaffolding, hung from supports inserted into holes in the upper walls near the windows. This allowed him to work on the various surfaces sometimes horizontally, sometimes vertically, sometimes transversely.

Due to the scaffolding's design, painting the vault had to proceed from the wall above the door towards the altar, tackling one bay at a time: besides the central panel, Michelangelo painted the corresponding spandrels and lunettes.

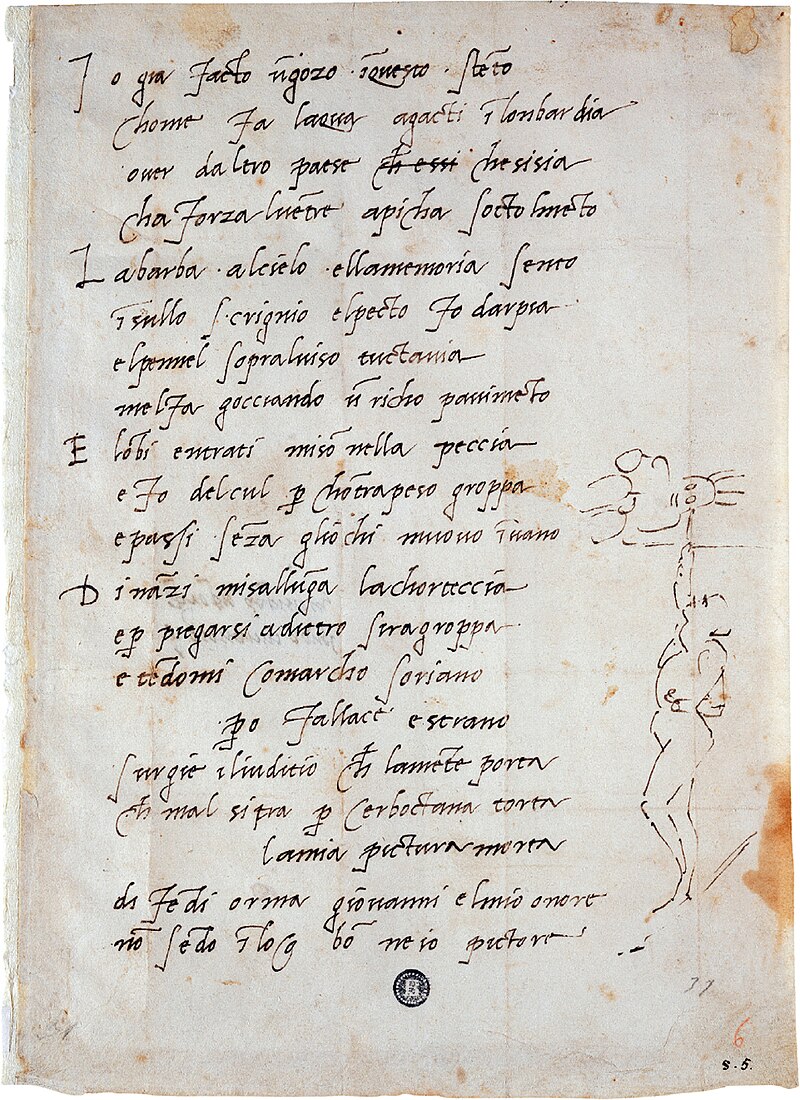

In practice, with this structure, Michelangelo solved the problems of height and mobility, but not that of comfort. While the legend that the artist had to work lying down is likely untrue, his working conditions were undoubtedly extremely harsh: the scant light filtering through the windows and scaffolding was supplemented by the uncertain and uneven illumination of candles and lamps; his head had to be bent backward, causing "greatest discomfort," so much so that when he came down, Michelangelo "could not read or look at drawings unless by holding them overhead, and this condition lasted for several months."

The work, exhausting in itself, was aggravated by the artist's characteristic self-dissatisfaction, delays in payment, and continuous requests for help from his family. Furthermore, the initial phases of the decoration were hampered by technical problems related to the appearance of mold; essentially, Michelangelo had used a lime and pozzolana mortar that was too watery instead of the usual lime and sand mix. To fix the problem, Michelangelo had to remove the intonaco and start over, this time using a new mixture that dried more slowly but had better durability.

The feeling of having undertaken an enterprise in which he was not sufficiently experienced and the initial difficulties led the artist to profound discontent, which he expressed in a letter to his father: "I am not in a good place, nor am I a painter." He is also reported to have written, "This is the difficulty of the work, and also that it is not my profession. And yet I am wasting my time without fruit. May God help me."

Pope Julius II climbed the ladder of the scaffolding

It is said that Michelangelo prevented Pope Julius II from coming to supervise. One day, the Pope, worried about his frail health and fearing he might die, impatient and eager to see this magnificent work finished quickly, climbed the ladder of the scaffolding and chided the artist for the slow progress, shouting, "When will you finish this chapel?" "When I can," Michelangelo replied coldly. The pontiff retorted, "When you can? You want me to have you thrown off this scaffolding!" To which the painter replied, "That is exactly what I challenge you to do," accompanying these words with such a look of anger that it immediately silenced the Pope, forcing him to climb down from the scaffolding with his head bowed.

Michelangelo, who did not trust the work of others, executed all the paintings of the Sistine Chapel himself. However, between the end of August and early September 1508, he summoned a group of assistants from Florence: they were experienced young men from the workshops of Ghirlandaio or Cosimo Rosselli. According to the Aretine historian (Vasari), Michelangelo had disagreements with them because he was dissatisfied with their work and dismissed them abruptly. So he hired others, but this time dedicated to more modest tasks like preparing colors and plaster.

By August 1510, almost half of the project had been completed. Stylistic studies have detected the presence of collaborative interventions at least until January 1511, after which the artist appears to have continued alone. In any case, they worked in absolute subordination to Michelangelo, with no freedom of action regarding the scenes to be depicted, following very detailed cartoons.

The scaffolding only covered half the chapel, so when the work on the initial part was finished, it had to be dismantled and rebuilt in the other half. It was on this occasion, between 1509 and 1510, that Michelangelo was able to get a first look at the result.

Julius II meets Michelangelo Buonarroti at Bologna (1475-1564 Florentine)

August 1510 marked a period of financial strain for the papal coffers, burdened by the Pope's military campaign against the French; the Pope was away and had left no orders for anyone to pay him for the completed half nor to give him an advance for the second part.

A few weeks later, Michelangelo left for Bologna to find the Pope and returned again in December, failing to obtain what he was seeking.

It was only in June 1511 that the Pope returned to Rome and had the scaffolding dismantled to see the results. The occasion was precious for Michelangelo, who could see the vault from below in its entirety and without the scaffolding. Realizing he had overcrowded the scenes with figures on a not-so-grand scale, making them hard to read from the thirteen meters separating the ceiling from the floor, he rethought his style for the subsequent frescoes. However, overall, the stylistic variations are not noticeable; indeed, seen from below, the vault has a perfectly unified appearance.

A sonnet by Michelangelo Buonarroti on painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling, accompanied by a sketch of himself in the act of painting. Probably to Giovanni di Benedetto da Pistoia. Pen and brown ink. Circa 1508–1512.

The frescoes were solemnly unveiled, and the chapel reopened shortly after, in October 1512. Upon observing the frescoes, the artist and the patron thought about finishing them with the addition of secco finishes (for drapery and other details) and gilding, which, however, were never executed, both due to the complexity of reassembling the scaffolding and because they were not strictly necessary. Vasari reports an exchange on the matter between Pope Julius and Michelangelo: "The Pope", often seeing Michelangelo, would say to him: "Let the chapel be enriched with colors and gold, for it looks poor." Michelangelo replied familiarly: "Holy Father, in those times men did not adorn themselves with gold, and those who are depicted were never very rich, but they were holy men, for they despised riches."

Ultimately, the difficult challenge could be considered a full success, beyond all expectations. Judgments on the result were immediately enthusiastic, and all the artists present in Rome went to see Michelangelo's astounding work.

By unveiling the completed paintings to the public, Buonarroti showed with what right he could display this sovereign dignity, having in twenty months (a common contemporary overestimation; the total was closer to four years with breaks) completed a work that sealed his artistic immortality.

The Sistine Chapel is a sacred building that reproduced the proportions of the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. It is dedicated to the Assumption of Mary into Heaven. It owes its name to Pope Sixtus IV (the uncle of Pope Julius II), who had the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican rebuilt and decorated. The original medieval "Palatine Chapel," which had fallen into disrepair, was later renamed in his honor as the "Sistine Chapel" and was intended to become the venue for the most solemn ceremonies.

Work began in 1477 and was completed in 1481. The chapel was restored by Baccio Pontelli in 1477 under Pope Sixtus IV (Francesco della Rovere, 1471-1484). Some of the greatest artists of the time, including Botticelli, Perugino, Ghirlandaio, and Pinturicchio, were called upon to fresco the walls. At that time, the ceiling was adorned with a vast starry sky, which was later replaced by Michelangelo’s famous frescoes. The vault plus the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel were completed by Michelangelo Buonarroti.

Julius II did not live to see his project for the Sistine Chapel completely realized, as in February 1513 he died from a fatal influenza-like fever caused by syphilis.

The Last Judgment

The history of Michelangelo's tomb for Julius was very troubled. It was originally intended for the old St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican. In 1545, thanks to an agreement with Julius II's heirs, Michelangelo created a scaled-down version of the tomb, which was placed in San Pietro in Vincoli. The Pope's remains currently rest inside St. Peter's Basilica itself, following their transfer from the original location.

Twelve years after completing the Sistine Chapel vault, Michelangelo returned there to work on another colossal undertaking: The Last Judgment, which occupies the entire altar wall.

Vatican City (Rome)