Rome, the ancient city

Rome, Italy

The site where Rome would one day stand was already inhabited in the second millennium B.C. However, it was only in the following millennium, with the gradual unification of its original villages, that the first foundations of the city took shape—a process completed in the 7th century under the rule of its earliest kings.

The Archaic Age (14th–8th Century B.C.)

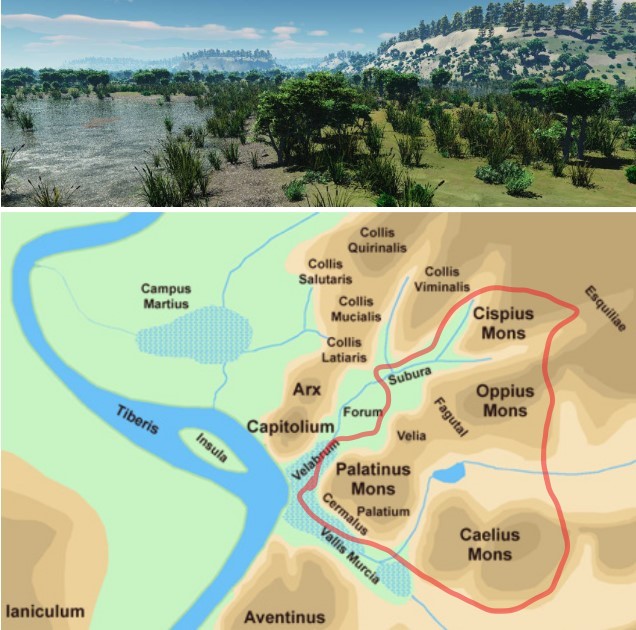

The place where Rome arose had long been a crossroads since the Bronze Age (14th–11th century B.C.), where land routes connecting central Italy to the south met the Tiber River, a vital waterway leading to the Tyrrhenian Sea. It was a natural meeting point for trade—a ford where merchants and travelers crossed, and a rudimentary harbor for small boats coming from the sea or inland.

View of the site where Rome would rise, seen from the Capitoline Hill toward the Aventine. In the center, the low-lying area where the river port would later emerge. (Source: archein.it)

On the hills (montes) overlooking the marshy banks of the Tiber, the first settlements emerged, home to tribes of farmers and shepherds, each with their own burial rites and customs. Within these primitive villages, social hierarchies were simple: an assembly of all able-bodied men held sovereign power, while elders guided the community.

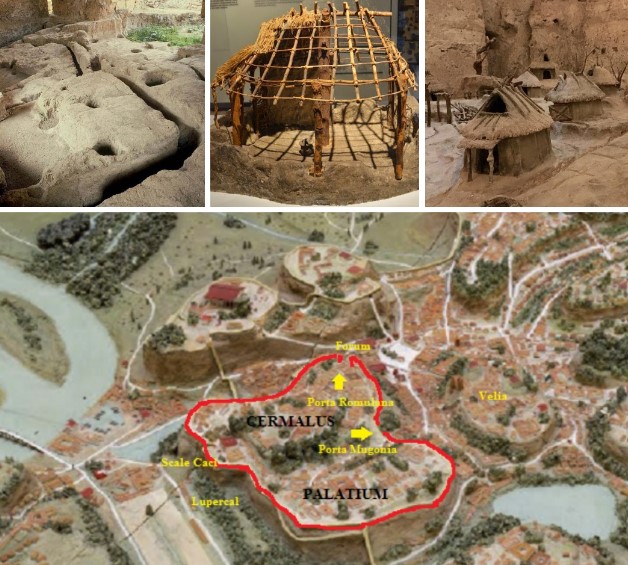

Between the 9th and 8th centuries B.C., these hills became known as the Septimontium or Saepti montes ("the linked mountains"), consisting of four main groups:

- Caelius (or Querquetual) and Subura

- Palatium and Cermalus (Palatine Hill)

- Cispius, Fagutal and Oppius (Esquiline Hill)

- Velia (connecting the Palatine and Esquiline Hills)

Later, these would expand into the famed Seven Hills with the addition of the Capitoline, Quirinal, and Viminal Hills.

Archaic Rome before its foundation: marshy land along the Tiber River and the Septimontium hills (red line).

[ca. 50 BCE] Where Rome now is, was called the Septimontium from the same number of hills which the City afterwards embraced within its walls; of which the Capitoline got its name because here, it is said, when the foundations of the temple of Jupiter were being dug, a human caput 'head' was found.

- Varro, On the Latin Language, 5.41

The Monarchical Era (8th–6th Century B.C.)

By the 8th century B.C., interactions between the hilltop villages intensified. Pastures and roads were shared, goods and techniques exchanged, and rituals performed together. The settlements grew denser around emerging religious centers.

The swamps left by the Tiber’s floods were drained and repurposed as farmland. Villages expanded their borders—the strong absorbed the weak, and communities merged. It was in this era that Roma Quadrata (square Rome), the legendary Rome of Romulus, was born.

According to myth, Rome’s founding traces back to the twin brothers Romulus and Remus, sons of Rea Silvia and the god Mars. Abandoned and suckled by a she-wolf, they were later raised by the shepherd Faustulus and his wife, Acca Larentia. Upon reaching manhood, the twins resolved to build a city. To decide who should rule, they sought divine guidance through the flight of auspicious birds. From the Aventine, Remus saw six vultures, but Romulus, standing on the Palatine, spotted twelve—thus becoming Rome’s first king in 753 B.C.

Roma Quadrata was likely a fortified village (pagus) on the Palatine, enclosed by a sacred boundary (pomerium), either a wall or a trench. It began as a union of small Latin villages before merging with Sabine communities on the Quirinal and Esquiline Hills. Its position was strategic, near the Tiber’s easiest crossing point—thanks to the Tiber Island.

From the Palatine, the city expanded across the Seven Hills: Palatine, Aventine, Capitoline, Quirinal, Viminal, Esquiline, and Caelian.

Square Rome, the remains of archaic huts with postholes for support beams, and the reconstruction of the hut village on the Palatine Hill. Square Rome refers to the earliest, legendary settlement on the Palatine Hill, traditionally considered the nucleus of ancient Rome. According to Roman mythology and historical accounts (like those of Livy and Plutarch), it was a ritually demarcated area established by Romulus, the city's founder, around 753 BCE.

By the late 7th century B.C., under King Ancus Marcius, Rome saw its first wooden bridge (Pons Sublicius) and the occupation of the Janiculum on the river’s right bank to secure the crossing.

View from Trastevere toward the Forum near the Pons Sublicius (built by Ancus Marcius, 642–617 B.C.).

In the 6th century B.C., Servius Tullius, Rome’s sixth king, oversaw the city’s definitive urban formation. The valley marshes were drained through the Cloaca Maxima, allowing the inhabited area (about 300 hectares) to expand beyond Romulus’ walls, stretching into the valleys of the Comitium and the Roman Forum.

Rome had become a true city, with public and religious buildings, paved streets, and a bustling civic life. The Comitium was the political heart, while the Forum served as both marketplace and meeting place. Aristocratic homes encircled the Forum, lining the Sacred Way leading to the Capitoline, near the Regia (the king’s residence) and the Temple of Vesta. The surge in temple construction—and the extensive use of terracotta for decoration—turned Rome into a thriving artistic center.

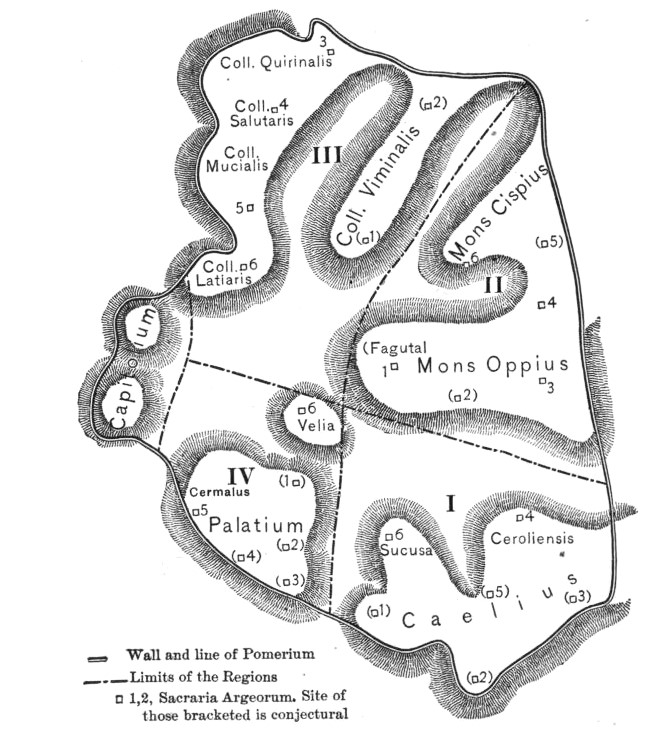

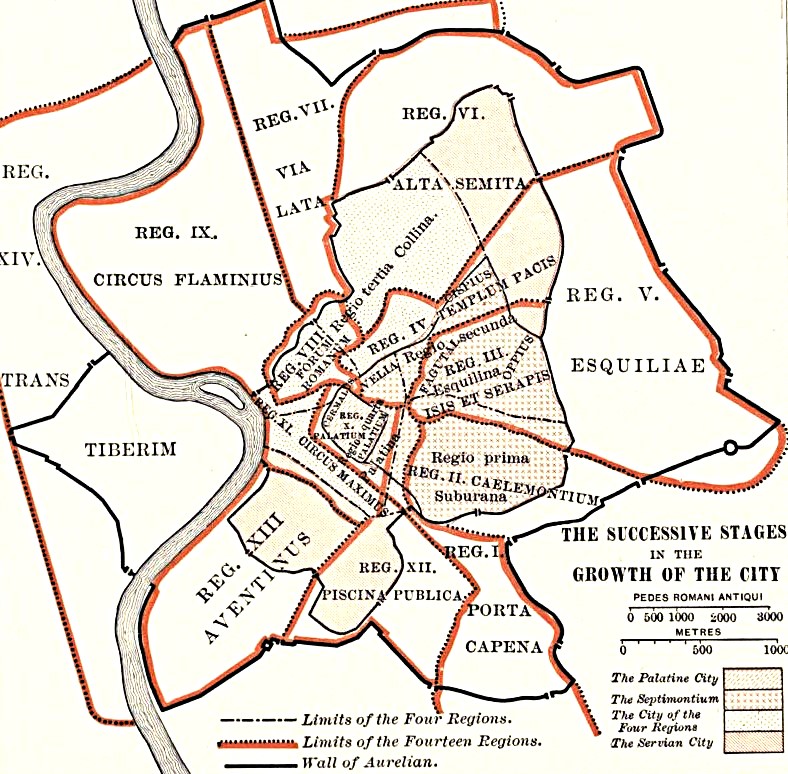

Servius Tullius divided the city into four districts (Regiones), which remained central until Augustus’ time:

- Suburana: The Subura ("city outskirts"), including the Caelian Hill.

- Esquilina: Named ex quiliae, "outside the settlement".

- Collina: Encompassing the Quirinal and Viminal Hills.

- Palatina: The Palatine Hill and Roman Forum.

The city of the four regions

The Republican Era (509–27 B.C.)

In the early 5th century B.C., construction continued, now influenced by Greek artisans—evidence of Magna Graecia’s cultural reach (e.g., the Temples of Saturn, the Castors, Ceres, and renovations to the Regia and Temple of Vesta).

In 456 B.C., a law granted the Aventine Hill to plebeian families, giving this once-marginalized area political significance.

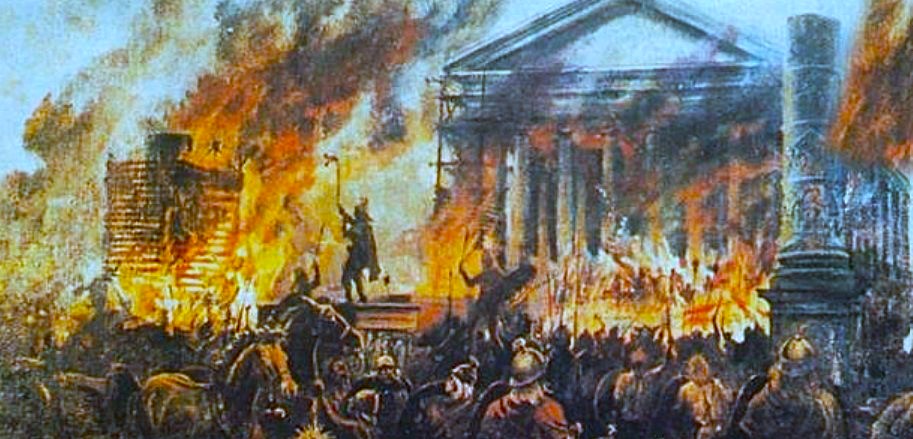

The late 5th century B.C. brought internal strife, wars with neighboring peoples, and a general Italian crisis, halting construction. This turmoil culminated in the Gallic sack of Rome (390 B.C.), a sudden and devastating invasion.

The only notable projects were in the undeveloped Campus Martius: the Saepta (voting enclosures), the Villa Publica (census grounds), and the Temple of Apollo (431 B.C.).

After the Gallic fire, Rome’s rebirth was hasty and chaotic. By the 4th century B.C., it covered 400+ hectares—larger than any contemporary Italian city.

A revival of construction followed: new temples, paved roads, and the Temple of Concord (367 B.C.), celebrating social peace. Key infrastructure included:

- The Aqua Appia, Rome’s first aqueduct (312 B.C.).

- The Via Appia, the famed road stretching beyond the city.

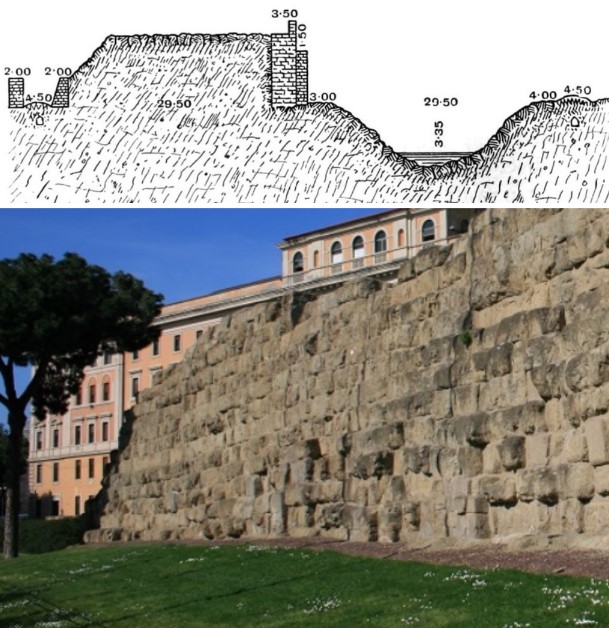

- New defensive walls of yellow tufa blocks (erroneously called "Servian").

Section of agger of Servian Wall between Porta Collina and Porta Esquilina

The Punic Wars (3rd–2nd century B.C.) and Roman Civil Wars (1st century B.C.) marked Rome’s rise and the Republic’s fall. Economic growth spurred urbanization, with temples funded by war spoils (e.g., Bellona, Jupiter Victor, Aesculapius, Janus).

Greek influences reshaped architecture: porticoes, basilicas, triumphal arches, and revolutionary concrete (opus caementicium). Marble replaced tufa in grand projects like the Temple of Juno Regina and Hercules Victor.

Elite domus with atriums and peristyles arose on the Palatine, Quirinal, and Esquiline, while slum-like insulae (apartment blocks) housed the growing populace.

To manage unchecked growth, Rome adopted Hellenistic urban planning:

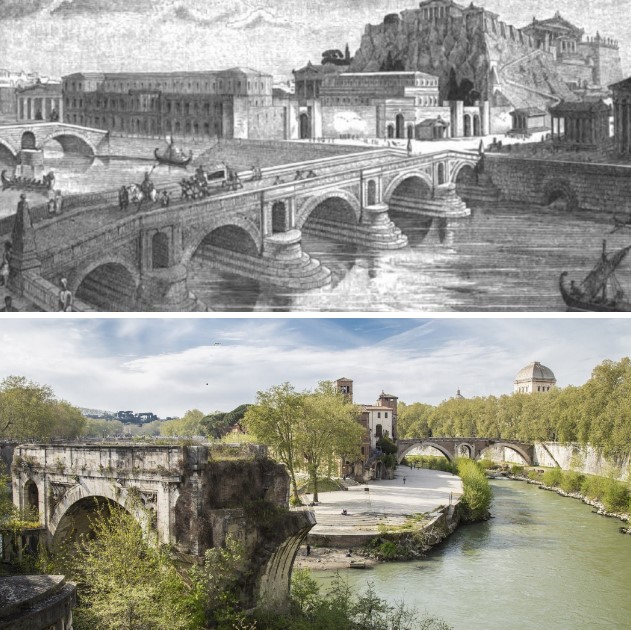

- The Pons Aemilius (178 B.C.), its first stone bridge.

- New aqueducts, paved roads, and renovated districts.

Pons Aemilius, 178 a.C.

Julius Caesar (100–44 B.C.) redeveloped the Subura and transformed the Forum: demolishing the Comitium, rebuilding the Senate’s Curia, and erecting the Basilica Julia.

Curia Iulia

Among the institutional seats of Ancient Rome, one of the most important was undoubtedly the Curia. This distinctive building takes its name from the curiate assemblies—citizens selected by wealth—held in the Comitium, the political heart of the city located in the Roman Forum. It was here that the Curia Hostilia, Rome’s first senate house, was said to have been built in the 6th century B.C. by Tullus Hostilius, the third king of Rome. Damaged by fire in 52 B.C. during the funeral of Publius Clodius Pulcher, it was entirely rebuilt by Julius Caesar, who reoriented it to a more dramatic position adjoining his Forum of Caesar. The building was then renamed the Curia Julia

Basilica Iulia

The Imperial Age

Augustus (63 B.C.–14 A.D.) completed Caesar’s vision, boasting he had "found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble." He built the Imperial Fora, Pantheon, Ara Pacis, and temples to Neptune and Apollo. Yet, he neglected the chaotic sprawl of plebeian districts like the Subura and Trastevere, where insulae towered 20 meters high.

To curb disorder, Augustus reorganized Rome into 14 regions, improving roads both within and beyond the city. Many modern Roman streets follow ancient paths:

- clivus Suburanus (via in Selci);

- clivus Scaurus (clivio di Scauro);

- via Sacra through the Forum;

- via Lata (via del Corso);

- vicus Iugarus leading to the river port;

- vicus Piscinae Publicae (viale Aventino);

- vicus Portae Raudusculanae (viale Piramide Cestia);

The Fourteen Regions of Augustus

Each region was divided into vici (neighborhoods), policed by barracks. This system endured until the Middle Ages, evolving into the Rioni.

By the 2nd century A.D., Rome peaked at over a million inhabitants, its skyline crammed with towering insulae.

Decline and Transformation

By the 3rd century A.D., the old Republican walls were obsolete. Facing barbarian invasions, Emperor Aurelian (270–275 A.D.) built new walls—19 km long, with 13 gates and defensive towers. These brick ramparts (7 meters high, 3.5 meters thick) enclosed landmarks like the Praetorian Camp, Claudian Aqueduct, and Pyramid of Cestius.

Yet, Rome’s political and economic decay led to urban decline. Barbarian raids, dwindling population, and neglect turned grand monuments to ruins.

From pagan glory, Rome transitioned into a Christian capital—its legacy enduring even as its grandeur faded.

The Aurelian walls

Rome, Via di Porta San Sebastiano, 18

museodellemuraroma.it