Secrets of Priscilla's Mausoleum

Rome, Italy

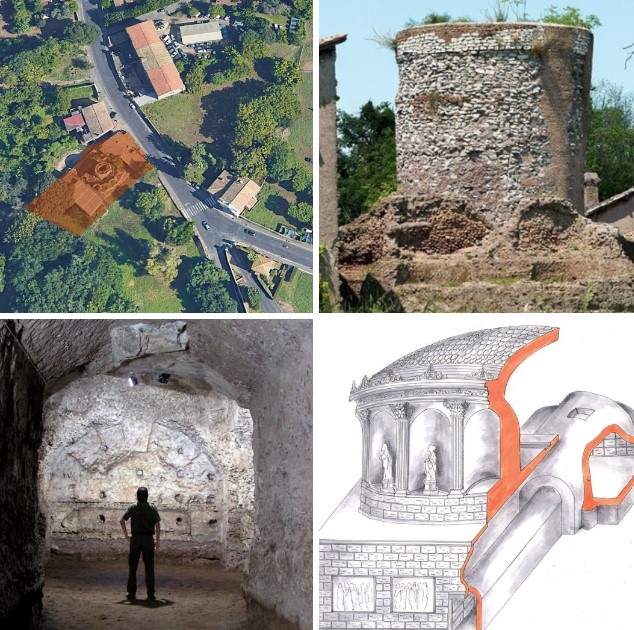

The Santa Maria Nova estate takes its name from Santa Maria Nova al Palatino, which, from the early 12th century, owned a vast latifundium on the Via Appia. This land lay within the area of the ancient villa belonging to the brothers Sextus Quintilius Condianus and Sextus Quintilius Valerius Maximus, members of a senatorial family and consuls in 151 AD. In 182-183 AD, Emperor Commodus accused them of plotting against him, had them killed, and seized their residence. The core of the farmhouse (Casale) was built in 1208, reusing the remains of a 2nd-century AD Roman building—possibly a two-story cistern—upon which a defensive tower had been constructed in Late Antiquity. Between the 15th and 16th centuries, the building took on its current form. Archaeological excavations in the areas outside the building uncovered numerous Roman-era structures: stretches of basalt-paved road, a 2nd-century AD burial area, and buildings likely belonging to the vast adjacent complex of the Villa of the Quintilii.

Santa Maria Nova Estate and Joseph Taylor's illustration depicting the "discovery" of the incorrupt body of a girl believed to be Tullia (1816)

In 1485, an ancient sarcophagus containing the embalmed body of a young girl was unearthed on the land of the Olivetan monks of S. Maria Nova (Geniales dies, III 2). The Neapolitan humanist lawyer Alessandro d’Alessandro (1461-1497) recounted that the corpse had an intact face, hair contained in a golden net, eyes, nostrils, and all features perfectly preserved, thanks to the ointments with which she had been anointed, which seemed like fresh aromatics. All those present at the discovery were astonished to see how, after 1500 years, the body showed no signs of deterioration. The corpse was transported to Rome, the ointment was removed, and after three days, it decomposed. Her identity remained unknown, as no inscription was found to identify the deceased.

Some hypothesized she was Tulliola (79-45 BC), the beloved daughter of Marcus Tullius Cicero and his first wife, Terentia. However, Tullia died at 32, and the discovered corpse was that of a young girl, so it was mere conjecture. Today we know her tomb is located in Formia, roughly 100 meters as the crow flies from her father's tomb, on the hill above. The area where her tomb was built was called Acervara, from the Latin acerbam (meaning bitter/untimely, as she died very young in childbirth) and ara (meaning altar, indicating the actual site). Tradition holds that the orator's bier was placed in the tomb after his hands and tongue—the symbols of the philosopher's eloquence—were severed. It is now certain his body was eventually buried in Rome, while his daughter remained in her mausoleum.

Mausoleum of Cicero and his daughter Tullia in Formia

Other scholars of the time instead hypothesized that she was Priscilla, the wife of Abascantus, but again, a confirming inscription was lacking. Furthermore, according to sources, she was buried near the River Almone, meaning she was on the ancient Appian Way about 10 km closer to Rome than the location where the girl's body was found. Crucially, she was far from being a young girl; in fact, she was older than her husband Abascantus.

Tomb of Priscilla

Titus Flavius Abascantus was the favored freedman of Emperor Domitian, becoming so powerful that he rose to become his secretary "ab epistulis" (in charge of imperial correspondence). The poet Publius Papinius Statius dedicated the fifth book of his Silvae to him. Within that work, the funeral song in honor of the freedman's wife is placed in the Epicedion in Priscillam Abascanti Uxorem.

On the ancient Appian Way, near the ancient River Almone—where the priests of Magna Mater washed the statue of the goddess—Abascantus owned land and a bath complex. He likely acquired an existing tomb on that land and adapted it for his own needs. Roman law forbade burial within the city walls. It was therefore customary for aristocratic families to build their tombs along the consular roads near the city, often within their suburban estates. The monumentality of family tombs signified the prestige of the various Roman families to those entering the city of the living from the outskirts.

Via Appia in ancient Rome by Pierers Universal-Lexikon, 1891

In the mid-1st century AD, the influential freedman lost his beloved wife Priscilla prematurely. He then decided to erect a funerary monument in her memory. Statius described the funerary structure as a building of considerable size, covered by a dome, and situated on the Via Appia.

The poet celebrates the solemn funeral of the young woman who died prematurely, a friend of his own wife, as declared in the dedication:

ego tamen huic operi non ut unus e turba, nec tantum quasi offlciosus assilui, amavit enim uxorem meam Priscilla, et amanda fecit illam probatiorem

Yet I approached this task not as one of the crowd, nor merely out of duty; for Priscilla loved my wife, and by being loved made her more virtuous.

In that writing, the poet shows that Priscilla's body was not cremated, as was Roman custom, but embalmed. Her remains were wrapped in Tyrian purple robes, enclosed within a marble sarcophagus. Her features were reproduced in statues resembling Greco-Roman goddesses and heroines, placed inside the tomb.

Hic te sidonio velatam molliter ostro

Eximius coniux (nec enim fumantia busta

Clamoremque rogi potuit perferre) beato

Composuit, Priscilla, toro. Nil longior aetas

Carpere, nil aevi poterunt vitiare labores

Siccatam membris. Tantas venerabile marmor

Sepit opes:

Here, gently veiled in Sidonian purple, O Priscilla, your exceptional husband (for he could not endure the smoking pyre and the clamor of the flames) laid you upon a blessed couch. No length of years can plunder, no toil of time can mar your limbs, dried thus. Such treasures does the venerable marble enclose.

The tomb was on the Via Appia just past the Almone stream..

Est locus ante urbem qua primum nascitur ingens

Appia, quaque italo gemitus Almone Cybelle

Ponit et idaeos iam non reminiscitur amnes

There is a place before the city where the mighty Appia first arises, and where Cybele lays aside her lamentations by the Almone, no longer remembering the Idaean streams.

The monument was covered by a dome (tholus), hence round in shape, and adorned with statues around it—therefore with niches. These statues, some bronze, some marble, represented Priscilla in the forms of Ceres, Ariadne, Maia, and Venus, mingled with other figures:

Mox in varias mutata novaris

Effigìes: hoc aere Ceres, hoc lucida Gnossis

Illo Maia tholo, Venus hoc non improba saxo,

Accipiunt vultus haud indignata decoros

Numina: circumstant famuli, consuetaque turba

Obsequiis: tum rite tori mensaeque parantur

Assidue: domus ista domus: quis triste sepulcrum

Dixerit ?

Soon transformed, you renew yourself in varied effigies: Ceres in this bronze, the bright Cretan [Ariadne] in this, Maia in that dome, Venus in this unoffending stone—the goddesses receive your features, not disdaining their grace. Attendants surround you, the familiar throng of servants: then couches and tables are duly prepared constantly: that house is a home: who would call it a gloomy tomb?

According to this description, Priscilla's tomb was sumptuous, round in shape with external niches containing statues, located on the Appia near the Almone. Its interior was fashioned not for cinerary urns but for sarcophagi. The Appia and the Almone are fixed, unquestionable points: precisely just past the Almone, on the right side of the Appia, almost opposite the church of Domine quo vadis (where, according to popular tradition, the Apostle Peter, fleeing Rome to avoid Nero's persecution, had a vision of Jesus – though the marble slab with the imprint of two feet – a copy of the original preserved in the nearby Basilica of S. Sebastiano – does not constitute proof of the miraculous event, being a typical pagan ex-voto for a successful journey), there stands a large semi-ruined circular monument. It rests on a large square base, originally covered by a dome ( tholus), later replaced in the late Middle Ages by a small tower built from broken marbles, spoils from the monument itself. The square base is constructed of flint rubble, suggesting it was once faced with stone blocks, traces of whose setting remain. On the side opposite the road is the entrance, leading to a burial chamber containing three niches for sarcophagi. Above this base, the semi-ruined round structure still suggests it was made of reticulate work (opus reticulatum) covered in stucco, with eight niches for statues. The structure is identical to other works from the Flavian period, and the forms are too analogous to Statius's description for there to be any doubt about the tomb's identity and nomenclature.

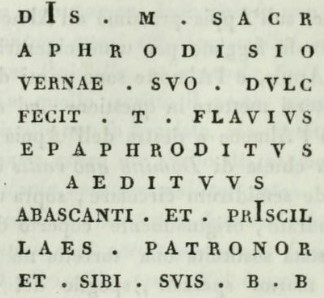

As further confirmation of what has been stated, during excavations around the monument in 1773, the following inscription was found, serving as evidence for recognizing it as the tomb of Priscilla. It records the name of Titus Flavius Epaphroditus, freedman of Abascantus and aeditus (custodian) of his tomb, and of Priscilla:

Because the tomb also received the body of Abascantus, Priscilla's husband, and because, according to custom, the freedmen and loyal servants of patrons were buried around their patrons' tombs. Epaphroditus, freedman of Abascantus and Priscilla, was the aeditus (custodian) of their tomb and preserved the names of his masters. He must have been buried near the monument he guarded.

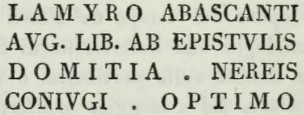

Besides the previous inscription, another was found nearby, belonging to Lanairo, a slave of Abascantus. From this, we learn that Abascantus was a freedman and secretary of the emperor (Domitian):

Since the preceding inscription shows that Epaphroditus, freedman of Abascantus, had the praenomen and nomen Titus Flavius, it follows that his patron Abascantus was also called Titus Flavius. He received these names from his patron Titus Flavius Domitianus (Emperor Domitian), who granted him freedom and entrusted him with the office of private secretary. Indeed, Statius later calls him a minister of Domitian who rebuilt the Capitol and the Temple of the Flavian Gens:

Est hic agnosco minister

Illius aeternae modo qui sacraria genti

Condidit atque alio posuit sua sidera coelo.

Here I recognize the minister of that eternal one [Domitian], who lately founded shrines for his race and placed his stars in another heaven.

From these inscriptions, knowing the connection to Abascantus and his wife Priscilla, who were buried at the site, it was established that the large surviving ruin indeed belonged to the described tomb of Priscilla.

The poet thus specifies that Priscilla was not cremated according to Roman custom but embalmed on Abascantus's orders. Mummification was a rare but not absent practice in the Roman world: another 2nd-century AD example is the young mummy of Grottarossa.

Priscilla's body was wrapped in Tyrian purple robes, covered in perfumes, and placed in a precious bier within a marble sarcophagus, inside a mausoleum on the Via Appia, immediately beyond the River Almone. The mausoleum, also intended for her husband, was adorned like a domus inside, with niches and bronze statues of heroines and female deities bearing the face of his beloved Priscilla. Confirming the identification, in 1773, a marble slab dedicated to the burial of the young slave Aphrodisius was discovered near the mausoleum. It was placed by Titus Flavius Epaphroditus, custodian of the tomb on behalf of his patrons Abascantus and Priscilla. The inscription, based on Epaphroditus's onomastics and the epigraphic style, dates to the second half of the 1st century AD, the Domitianic period, coinciding with the tomb's construction. The slab is preserved in the civic lapidary museum in Ferrara, where it arrived in 1779 following a donation by Cardinal Gian Maria Riminaldi.

The tomb was plundered at an unknown date, stripped of its coverings and bronzes, and reduced to a ruin. It was reused from the 11th century as a fortification: a cylindrical tower ("Torre Petro") was built on the upper cylinder using spolia. It belonged to the Counts of Tusculum and later passed to the Caetani family. In the 18th century, it was erroneously believed to be the tomb of the Scipio family. Giovanni Battista Piranesi studied its plan and depicted it in a famous etching.

In modern times, two farmhouses were built against it; one was the "Osteria dell'Acquataccio," and the burial chamber was used as a cheese-aging room. Recently, it was restored by the Superintendency (Sovrintendenza) and is only open for visits on special occasions.

Via Appia Antica, 76 (Roma)