The Enigmatic Death of Raphael and the Mystery of His Skull

Rome, Italy

One of the most famous cold cases in the history of art is the death of Raphael Sanzio (1483–1520) and the mystery surrounding his skull. Not everyone may know that his body now lies beneath the grand dome of the "Temple of All Gods," the Pantheon—and that for centuries, doubts have lingered over whether those remains are truly his.

Raffaello Sanzio and his hometown Urbino.

The Life of Raphael

Raphael was born into a well-to-do family in Urbino. An only child, he was the son of Maria di Battista di Nicola Ciarla and Giovanni Santi (c. 1440–1494), a painter of considerable skill and a learned humanist at the court of Federico da Montefeltro. His parents lavished him with affection, and young Raphael spent his childhood immersed in the colors and brushes of his father’s workshop, as well as in the Montefeltro court, where the greatest artists of the time gathered. Within the halls of the Ducal Palace, he admired the works of illustrious painters and mingled with the many luminaries who frequented the ducal city during an era of extraordinary cultural and artistic brilliance. Following in his father’s footsteps, Raphael learned the art of painting, mastering the grinding of pigments and the handling of brushes.

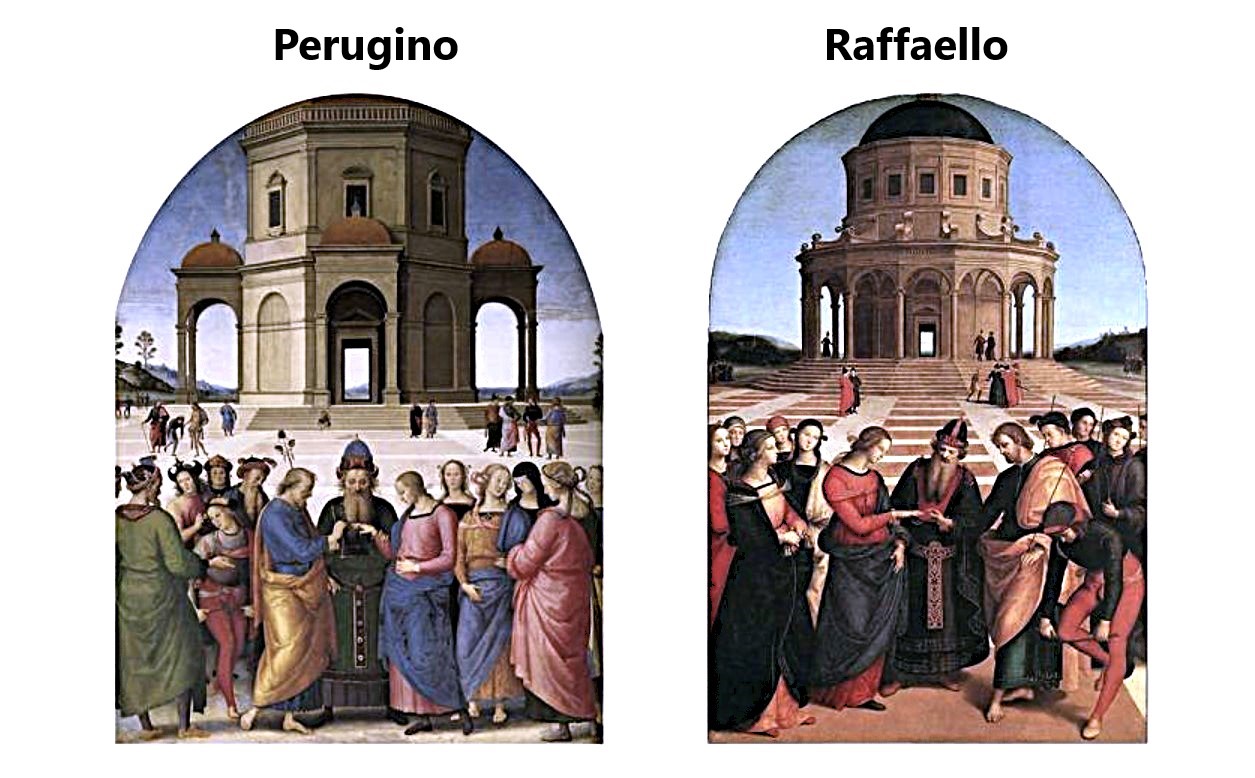

His happy childhood was abruptly cut short: at eight, he tragically lost his mother, and at eleven, his father. Left an orphan, he joined the workshop of Pietro di Cristoforo Vannucci, known as Perugino (1448–1523), and began enriching his artistic education by accompanying his master across Umbria and the Marche regions. He studied Perugino’s techniques, only to surpass them, proving to his patrons that he was a far more gifted painter. A striking example was his commission for The Marriage of the Virgin (1504): Raphael explicitly referenced Perugino’s treatment of the same subject, adopting its spatial composition but refining and improving every single detail.

Raphael, The Marriage of the Virgin, 1504, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan; Perugino, The Marriage of the Virgin, 1501-1504, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Caen.

From a very young age, the artist from Urbino demonstrated an unparalleled talent for capturing the essence of femininity—more so than any of his contemporaries. In Renaissance portraiture, women were often depicted as objects of male desire, but in Raphael’s work, they radiated intelligence and self-awareness.

By the age of sixteen, Raphael was already an entrepreneur and shrewd strategist, running his own workshop in Città di Castello and handling numerous commissions, including legal and administrative matters. In the following years, he became one of the most sought-after artists in Umbria. After brief stays in Florence and Rome, he joined Pinturicchio (1454–1513) in Siena.

Between the late 15th and early 16th centuries, the finest artists flocked to Rome from Florence, serving the popes and elevating the golden age of the Renaissance to its zenith. It was then, at just twenty-five, that Raphael’s career took a dramatic turn: Pope Julius II (1503–1513) summoned him to Rome to contribute to the city’s artistic and urban renewal, a project already underway under masters like Michelangelo and Bramante. According to Vasari, it was Donato Bramante (1444–1514) himself who recommended Raphael to the Pope. From that moment until his death, Bramante acted as the young artist’s mentor. Their collaboration was immediate—not only did Bramante teach him the fundamentals of architecture, but upon his death, he designated Raphael as his successor to complete the unfinished project of St. Peter’s Basilica.

Raphael, hailed as a universal genius alongside Leonardo (1452–1519) and Michelangelo (1475–1564), moved to Rome. As soon as he displayed his mastery, he became the Pope’s favorite artist, entrusted with decorating the Vatican Rooms. He also received numerous private commissions, particularly from the papal banker Agostino Chigi (1466–1520), a key figure in understanding Raphael’s success.

Popes: Giulio II (1443 – 1513), Leone X (1475 – 1521) and Agostino Chigi (1466-1520)

Chigi, a wealthy Sienese banker, earned various epithets over time: "The Magnificent," "God’s Banker," or, as the Ottoman Sultan called him, "The Great Merchant of Christendom." A shrewd and intelligent bourgeois, he financed bloody military campaigns, lent money to Popes Alexander VI, Julius II, and Leo X, and—being a man of letters with a taste for opulence and art—commissioned works from artists of Raphael’s caliber, with whom he shared a close friendship.

After his initial artistic trials, Raphael convinced the Pope that he could work independently—yet unlike Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel, he did not dismiss his assistants. Instead, he trained and led a team.

With the election of the Medici Pope Leo X (1513–1521), Raphael found himself managing an overwhelming number of commissions. Thanks to the discerning eye he inherited from his father, he enlisted specialized artists as collaborators, ensuring that every client received works of the same refined quality.

After the death of his fellow countryman Bramante in 1514, Raphael inherited the role of chief architect for St. Peter’s Basilica. The Pope entrusted him with cataloging ancient marbles, studying the Pantheon’s architectural elements, and drafting a map of Imperial Rome—an ambitious and complex project left incomplete due to the master’s sudden death. With an archaeologist’s zeal, Raphael also oversaw excavations of ancient Rome, beginning to document its buried heritage. Given his passion for antiquity, he was appointed "Conservator of Roman Antiquities," becoming the foremost advocate for an ideal reconstruction of ancient Rome.

Raphael died unexpectedly at the peak of his career at thirty-seven, after a brief illness, still deeply devoted to art and women. His death sent shockwaves through the artistic world, coming just a year after the passing of another universal genius, Leonardo da Vinci, on May 2, 1519.

The Mysteries Surrounding Raphael’s Death

The great artist from Urbino died between April 6 and 7 at 3 a.m. on Good Friday, after fifteen (or eight) days of "continuous and acute" fever and spasms caused by his "amorous excesses," as Giorgio Vasari recounts in his work Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. Indeed, Raphael’s contemporaries were well aware of his insatiable passion for beautiful women and the high life, which may have led him to contract syphilis. Others, however, attributed his demise to sheer exhaustion from overwork. The physicians of Pope Leo X, who visited him repeatedly, attempted a bloodletting—though there was little else they could do, and the treatment unsurprisingly failed.

Researchers from the University of Milan-Bicocca’s History of Medicine department conducted studies based on direct and indirect accounts of the time to determine the cause of Raphael’s death. Their findings ruled out malaria, typhus, and syphilis, instead pointing to pneumonia—whether bacterial or viral remains unclear, but its symptoms align best with the descriptions: an acute yet not immediate progression, no loss of consciousness, absence of gastrointestinal distress, and persistent fever. The bloodletting, strictly contraindicated for pulmonary fever, likely worsened his condition by further weakening him.

Honours paid to Raphael after his death (1806) by Pierre Nolasque Bergeret

Raphael’s death was mourned as an unprecedented tragedy. The fact that he died on Good Friday—the same day as his birth, April 6, 1483—fueled the perception of him not just as an artist but as a divine figure, a new Christ. Contemporary chronicles describe the shock that gripped the entire papal court. Despite his youth, Raphael’s fame had spread across Europe’s courts, and his peers quickly fostered the legend of his "divine origin," even considering him a reincarnation of Christ. Supporting this theory was the fact that Raphael, son of the painter Santi, signed his works in Latin as "Sancti" (Saints).

News of his death spread rapidly, eliciting disbelief and sorrow. Among those present in the Borgo Nuovo palace where the artist lived (steps from St. Peter’s) was the Venetian nobleman Marcantonio Michiel, who recorded in his diary the extraordinary events he witnessed at the moment of passing:

The sky darkened and grew turbulent; then a crack appeared in the house’s wall, while a steady stream of visitors filed into the bedroom where, just days earlier, his final masterpiece, The Transfiguration, had been placed.

A detail of 'The Transfiguration'(1516-1520) by Raffaello, Pinacoteca Vaticana

When Raphael died, as Vasari recounts, his last work—The Transfiguration, a large altarpiece completed by his pupils, chiefly his most trusted assistant, Giulio Romano (1499–1546)—was carried to his bedside. Vasari writes that seeing the painting, with Christ at its center, alongside the dying Raphael, "made every onlooker’s soul burst with grief."

That night, an earthquake struck, leaving a fissure in the Vatican Palace’s Logge ceiling—an event interpreted as an omen, likened to the rending of the Temple of Jerusalem’s veil at Christ’s death.

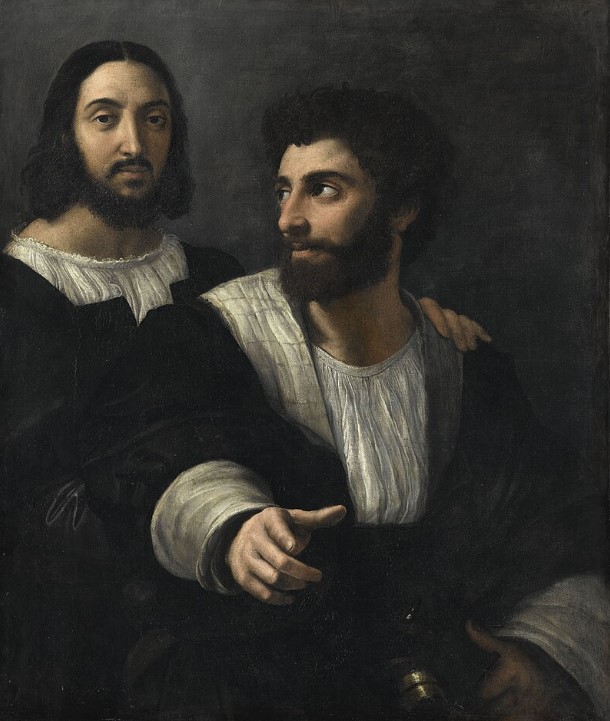

Self-portrait Raphael Sanzio with a friend, c. 1518, Louvre Museum, Paris

Moreover, Raphael’s physical resemblance to traditional depictions of Christ reinforced these comparisons. As seen in his Self-Portrait with a Friend, his long, straight hair parted down the middle and his beard gave him an aura of nobility and beauty that "resembled that which all excellent painters portray in Our Lord."

In his account penned shortly after the tragedy, Marcantonio Michiel noted how the cultural world’s grief was unanimous—and how preparations were already underway to honor the artist with "careful compositions." Evidently, literati immediately sought to poetically sublimate the collective sorrow. Likely spurred by Pope Leo X’s request for an epitaph to adorn Raphael’s tomb, a flurry of compositions emerged. The winner, according to Vasari, was the epitaph penned by Venetian humanist and friend Pietro Bembo. It reads:

Here lies Raphael, by whom Nature herself feared to be outdone while he lived, and when he died, feared that she herself would die.

Pantheon - Statue of Madonna of the Rock.

As you enter the Pantheon, also known as the Chiesa Santa Maria ad Martyres (Church of Saint Mary and the Martyrs), the third aedicule altar on the left is named for Our Lady of the Rock. It is one of the more popular attractions within the Pantheon, as it features the tomb of the great artist Raphael below the statue shown here. The statue - called Madonna del Sasso, or Madonna of the Stone, after the rock under Mary's left foot - was sculpted in 1524 by Lorenzo Lotti (Lorenzetto), one of Raphael's pupils. To the left of the statue is a bust of Raphael, which was sculpted by Giuseppe Fabris in 1833.

What is perplexing is that, despite his youth, Raphael had already made arrangements in the event of his premature death. He dictated his last will, expressly requesting burial in the Pantheon (a temple in classical times, later renamed Santa Maria Rotonda in 1000, now a minor basilica). He left a substantial sum for the chapel’s maintenance and decoration, executed by his pupil Lorenzo Lotti, called Lorenzetto, who in 1524 sculpted the Madonna del Sasso for the niche above the tomb. This large statue, modeled after an Aphrodite designed by Raphael for his burial, remains the only unchanged element in the niche since the 16th century. Long before his death, Raphael had personally restored the niche, intending it as his final resting place—a choice reflecting the Pantheon’s symbolic significance. Pope Leo X granted his wish, deeming him the greatest artist, worthy of lying in the Pantheon.

Raphael and the niece of Cardinal Bibbiena.

When Raphael died, his young lover, Margherita Luti (1500–?), was by his side. On April 7, 1520, a solemn funeral was held at the Pantheon. Friends and poets composed sonnets and songs dedicated to the "divine" painter. A vast crowd attended the rites, and a long procession accompanied him to the Pantheon. Conspicuously absent, however, was perhaps the most important person in the artist’s life—his beloved. Leo X had ordered Margherita barred from the ceremony, which was attended by Cardinal Bibbiena, still grieving his niece’s recent death.

Indeed, Raphael had been expected to marry Maria Dovizi da Bibbiena, niece of Cardinal Bernardo, one of Pope Leo X’s most influential associates—a match deemed ideal for a man of his stature. Yet Raphael delayed the wedding so long that the unfortunate Maria died before they could marry.

The Portrait of a Young Woman (also known as La fornarina) is a painting by the Italian High Renaissance master Raphael, made between 1518 and 1519

The painter had no desire to wed the cardinal’s niece because he was in love with the very young Margherita Luti. Some historical sources even suggest the two had secretly married. Seventeen years his junior, Margherita was said to be the daughter of a poor Trastevere baker (hence her nickname, "La Fornarina"), who could not afford a delivery boy and sent her out to do deliveries at dawn dressed as a boy. Other accounts claim she was a courtesan. Whatever her past, her humble origins made her an unsuitable match in the eyes of society.

Legend has it that Raphael first noticed her as she leaned out her window, drying her sunlit hair—soft, flowing locks she often left loose over her shoulders, bare under the thin blouses of the time. It was love at first sight. He asked her to model, and she, flattered, agreed. They fell deeply in love, and the artist kept her portrait with him until his death.

The Funeral of Raphael, work by Pietro Vanni, 1896-1900, oil on canvas. Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Contemporary Art Collection.

In the funeral procession accompanying the coffin, one can recognize Michelangelo, Perugino, and Albrecht Dürer, with whom Raphael had exchanged many letters..

Conspiracy Theories

Unverified conspiracy theories suggest Raphael belonged to secret sects and was murdered in a plot. This speculation stems from interpretations of his final painting, The Transfiguration, linked to Ezekiel’s vision. However, the subjects were likely suggested by his Augustinian superior, Egidio da Viterbo—it is doubtful Raphael or his workshop fully grasped any hidden meanings.

Just days after his death, his great friend and patron, banker Agostino Chigi, also died. Though he had become a father less than a month prior, he had already drafted a will. His mysterious demise was compounded by his wife’s suicide a year later.

Rumors of poisoning also surrounded the deaths of Baldassarre Peruzzi and two of Raphael’s greatest patrons: Cardinal Bibbiena and Pope Leo X.

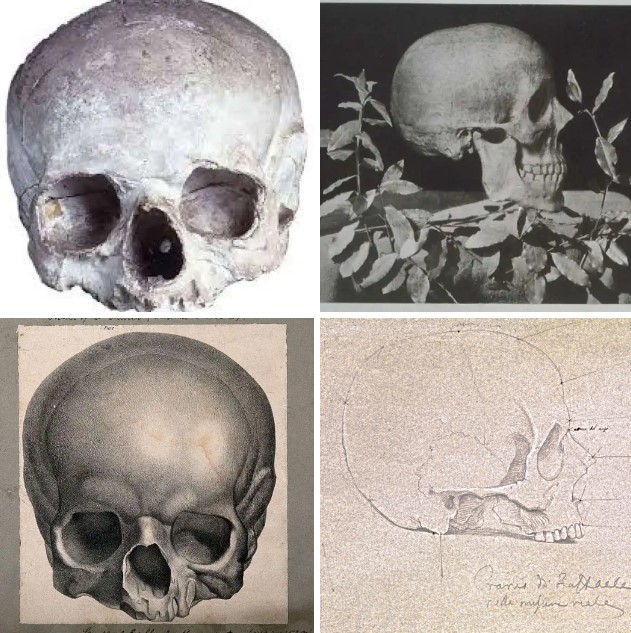

Copy of the cast of Raphael Sanzio's skull by Goethe, Turin; Raphael's exhumed skull in 1833, copy of the skull cast at the Accademia di San Luca, Rome; drawing of Raphael's skull (c. 1833), pencil on paper by Tommaso Minardi (1787–1871), London.Copy of the cast of Raphael Sanzio's skull by Goethe, Turin; Raphael's exhumed skull in 1833, copy of the skull cast at the Accademia di San Luca, Rome; drawing of Raphael's skull (c. 1833), pencil on paper by Tommaso Minardi (1787–1871), London.

How Many Copies of Raphael’s Skull Exist?

The first exhumation of Raphael’s remains occurred in 1674 by Carlo Maratta, Prince of Rome’s Accademia di San Luca (an artists' association founded in 1593 to elevate their craft above mere craftsmanship) and restorer of Raphael’s Vatican frescoes. With the Church’s approval, Maratta inspected the tomb at the Pantheon and extracted the skull to serve as a model for a bust by sculptor Paolo Naldini, now housed at the Accademia di San Luca. He also sealed the epitaph of Raphael’s "non-wife."

After Maratta’s discovery, Raphael’s skull was mistakenly swapped with that of a humble Cistercian monk, Desiderio Adjutorio, a mix-up only corrected in 1893, when the monk’s skull was finally returned.

Since then, numerous copies of Raphael’s skull have been made: aside from Maratta’s cast, Goethe commissioned one, displaying it proudly on his desk. Another supposedly lies buried—though comparisons with contemporaneous skulls, like that of Giovanni dalle Bande Nere, raise doubts. Fragments of Raphael’s bones, taken by French painter Ingres during his time in Rome, are even preserved at the Ingres Museum in Montauban.

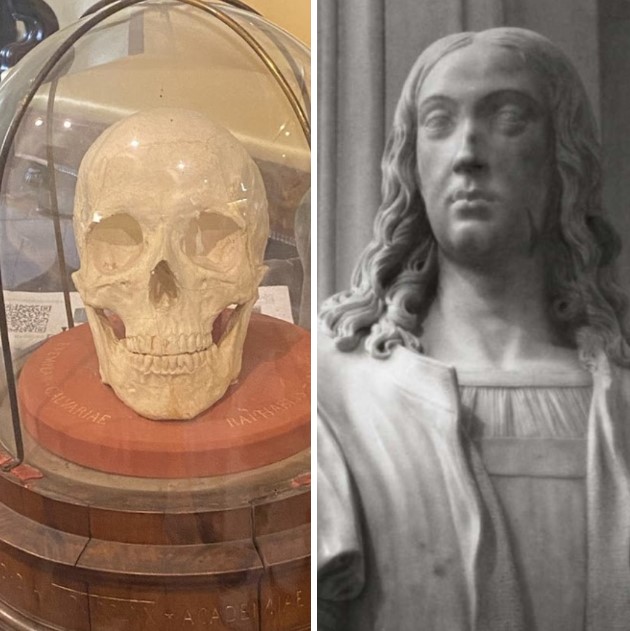

Cast of Raphael’s skull donated in 1870 (Casa Raffaello - Via Raffaello, 57, Urbino) and Raphael Sanzio, bust by Pietro Paolo Naldini.

Nearly two centuries later, in 1833, the tomb was reopened by the Pontifical Academy of Fine Arts and Letters of the Virtuosi al Pantheon (an academy founded in the 16th century to promote Christian-inspired art and literature) to settle the debate over whether the skull held by the Accademia di San Luca was authentic. Some believed Raphael was not buried in the Pantheon at all, while an old Roman antiquities commissioner claimed he lay in Santa Maria sopra Minerva.

1833: The opening of Raphael’s tomb (painting by Francesco Diofebi) and the discovery of his skeleton.

Guided by Vasari’s account, which located the burial beneath the Madonna del Sasso statue, excavation began on September 9, 1833, under the watch of experts. After five days, a wooden casket was found containing a nearly intact skeleton. Contemporary physicians declared it Raphael’s, and an official document attested to the burial. A second funeral was held, and his "bones and ashes" were placed in a 1st-century Roman sarcophagus donated by Pope Gregory XVI, where they remain today alongside Bembo’s epitaph.

ILLE HIC EST RAPHAEL TIMUIT QUO SOSPITE VINCI

RERUM MAGNA PARENS ET MORIENTE MORI

A bust of Raphael by Giuseppe Fabris was sculpted for the occasion, and plaques were reinstalled, including one commemorating Maria Bibbiena and painter Annibale Carracci, buried there by his own request.

Sarcophagus of Raphael Sanzio.

Prince Pietro Odescalchi, present at the exhumation, described the moment:

When we saw the arch’s summit emerge behind the altar, beneath the Madonna del Sasso statue, all present spontaneously cheered and applauded, their echoes resounding through the august temple.

Once the full arch beneath the statue was uncovered, Cavaliere Gaspare Salvi—President of the Accademia di San Luca and a distinguished professor of architecture—pointed out that its construction was neither modern nor ancient, but rather appeared hastily executed. The reason, he suggested, lay in the circumstances of Raphael’s death: having passed away on Good Friday night, his body was interred the following Saturday evening, and the arch’s cavity had been quickly filled and sealed before the dawn of Easter Sunday.

By the late morning of September 14th, the remnants of a wooden casket were unearthed—initially mistaken for pine, but upon closer inspection, revealed to be fir. Time and the seepage of moisture had fused much of the coffin with the mortar, leaving it nearly indistinguishable from the surrounding masonry.

As the team cleared away debris from the arch, fragments of human bones emerged—scattered in disarray, yet with a haunting dignity. The skeletal hands lay crossed over the chest, the skull slightly bowed as if in repose... and every tooth still startlingly white.

With meticulous care, the bones were cleansed of rubble and the ashen residue of Raphael’s mortal remains—relics now reverently sealed within protective vessels. Once reassembled, the skeleton was measured: from crown to heel, it spanned seven palmi, five oncie, and three architectural minuti (roughly 167 cm) by the ancient Roman scale.

A Lingering Mystery

Yet even years later, whispers of doubt still swirled around the tomb—was this truly Raphael’s final resting place? In 1930, another investigation was launched, and a hidden cavity was discovered beside the so-called Tomb of Raphael, revealing yet another headless skeleton.

This was not the first twist in the tale. But the confusion ran deeper. The Pantheon had long been a coveted burial site for illustrious figures, and records of its graves were notoriously muddled. The Neapolitan architect, painter, and antiquarian Pirro Ligorio (1513–1583) claimed that in 1536, the tomb meant for Raphael had also received the remains of Baldassarre Peruzzi. Other chronicles insisted that Annibale Carracci was buried in the same spot. The truth? Lost to time.

Even the 1833 exhumation by the Virtuosi, though solemnly documented in a notarial act, left puzzling gaps. They declared they had found Raphael’s body—despite uncovering other bones nearby—and described the skeleton with arms gracefully folded over its chest, an unlikely pose given the Tiber’s frequent floods that would have jostled the remains. Stranger still, they noted all teeth were intact and white, though historical sources suggest Raphael suffered from prognathism, a jaw misalignment that should have left telltale marks.

And then there was the skull. The cast preserved at the Accademia di San Luca bore no resemblance to the one unearthed in 1833.

So whose bones truly lie beneath the Pantheon’s hallowed dome? The mystery endures, wrapped in the same enigma that surrounded the artist in life—elusive, luminous, and just out of reach.

Tor Vergata University in Rome | The 3D reconstruction of Raphael Sanzio.

In 2020, Rome’s Tor Vergata University, in collaboration with the Vigamus Foundation and Urbino’s Accademia Raffaello, created a 3D facial reconstruction of the 1833 skull. Today, compared to Raphael’s self-portraits and contemporary depictions, it strongly suggests the Pantheon tomb does indeed hold his remains.

Rome, Piazza della Rotonda