Pancratius: The Boy Martyr Whose Courage Echoed

Rome, Italy

Pancras was born in 289 AD in Phrygia (a historical region in modern-day western Turkey) to Cleonius and Cerada, both noble pagans who raised their only son in their faith. He was orphaned at a young age: his mother died giving birth to him, and he lost his father at just eight years old. Before dying, Cleonius entrusted the boy to his brother Dionysius, who was appointed administrator of the wealthy family’s estates in Phrygia and Rome. Dionysius pledged to provide Pancras with an excellent education.

Seeking to distance him from the painful memories of his parents’ deaths and to introduce him to other relatives, around 299 AD, his uncle decided to take him to Rome—the epicenter of culture and science at the time—where Pancras could also prepare for a military or political career.

Their ship docked at various port cities across Greece and the Italian Peninsula. After landing at Ostia, uncle and nephew headed to Rome. There, they encountered a vibrant Christian community devoted to the crucified and risen Lord. Both underwent rigorous catechism and were admitted into the Christian community during a solemn Easter Vigil, likely baptized by Pope Marcellinus. Days later, Dionysius died of natural causes.

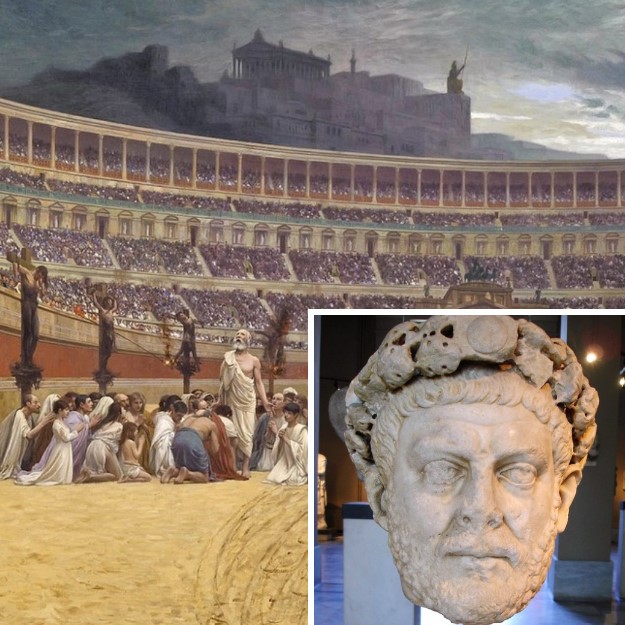

Istanbul - Archaeological Museum - Statue head of the Roman emperor Diocletian (284-305 AD)

Rome had just erupted in violent anti-Christian riots following the Fourth Edict in late April 304. This persecution—primarily orchestrated by Galerius Maximian, not the ailing, disillusioned Diocletian (emperor from 284–305)—marked the empire’s last and bloodiest campaign against Christians, claiming about 15,000 lives.

Filled with martyrdom zeal, Pancras was arrested and brought before a judge. When questioned about his identity, the teenager firmly replied: I am Pancras, and I am a Christian.

The judge tried relentlessly to compel him to worship the emperor. The young Christian stood unwavering: he would never renounce Christ for any man’s favor, even the Emperor of Rome. Forced to uphold the law, the judge ordered Pancras beheaded outside the city on the Via Aurelia.

Entrance to the second region of the Catacombs of San Pancrazio (or Octavilla), with an ancient plaque (bottom right) marking the martyrdom site.

He was executed in the presence of the pious Roman matron Octavilla, who, devastated by the boy’s fate, secretly retrieved his head and body under cover of night. She buried him in a nearby cemetery, likely her family’s burial ground (the catacombs are also named "Octavilla"). This occurred on May 12, 304; Pancras was only fourteen.

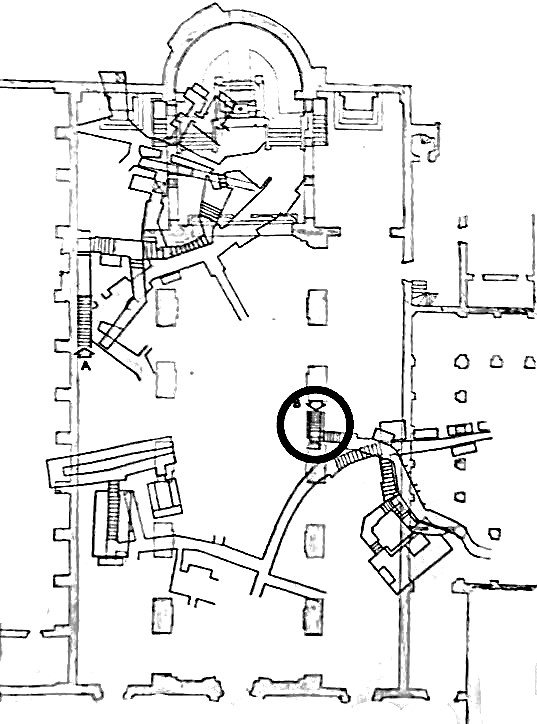

The martyrdom site is believed to be at the entrance of the underground cemetery—one of Rome’s few catacombs always accessible to pilgrims. Nearly two centuries later, Pope Symmachus (498–514) enshrined the martyr’s remains in a new church built over his tomb. Archaeological excavations in the 1930s confirmed that beneath the current basilica lie the portico of an important domus (likely Octavilla’s residence), a Roman road bisecting the site diagonally, and an open-air cemetery. Discoveries include mausoleums and ground tombs inside the basilica and its forecourt, proving the hypogeum cemetery extended above ground.

Floor plan of the Basilica of San Pancrazio, Rome, showing remains of earlier structures.

Pancras’s fame soared after Symmachus dedicated the basilica. Rome’s Christian community gathered there on the Sunday after Easter to present the newly baptized—who laid their white baptismal garments on his altar—praying for courage and faith like his.

The purported skeleton of St. Pancras in St. Nikolaus Church, Wil (Switzerland). Baroque silver reliquary of the catacomb saint Pankratius.

Pope Vitalian later sent Pancras’s relics—among others—to the Anglo-Saxon King Oswy, cementing his cult globally. Inscriptions from 521–522 attest to believers’ desire to be buried near his "glorious ashes." Romans flocked to his tomb to swear oaths, as Pancras was feared as a fierce punisher of perjury: Panchratus martyr valde in periuribus ultor

(Pancras the martyr, mighty avenger of false oaths). Pope Pelagius (556–561), accused of Pope Vigilius’s death, famously swore his innocence at Pancras’s tomb.

Devotion spread beyond the Alps. Invoked against false oaths, he was revered as the "guardian of oath sanctity"—French kings invoked him when ratifying treaties. By the time of Pelagius II (579–590), relics of Pancras and other Roman martyrs had reached France. Palladius, Bishop of Saintes (d. 596), dedicated his new basilica to Pancras, Peter, Paul, and Lawrence; Gregory the Great sent him relics. In England, Augustine of Canterbury rededicated a pagan temple of King Æthelberht to Pancras.

The saint’s sixth-century popularity likely spurred the earliest (and often embellished) legends. Church custodians (aeditui) probably crafted tales for pilgrims—Prudentius and Gregory of Tours recorded similar oral traditions at martyrs’ shrines.

Façade of the Basilica of San Pancrazio, Rome.

The Basilica of San Pancrazio stands on Rome’s Janiculum Hill, just outside the Aurelian Gate (renamed "San Pancrazio Gate" after the Gothic War, 535–553). This ancient paleo-Christian martyrial church, a minor basilica, was founded c. 500 AD by Pope Symmachus over the martyrdom site of the Phrygian saint.

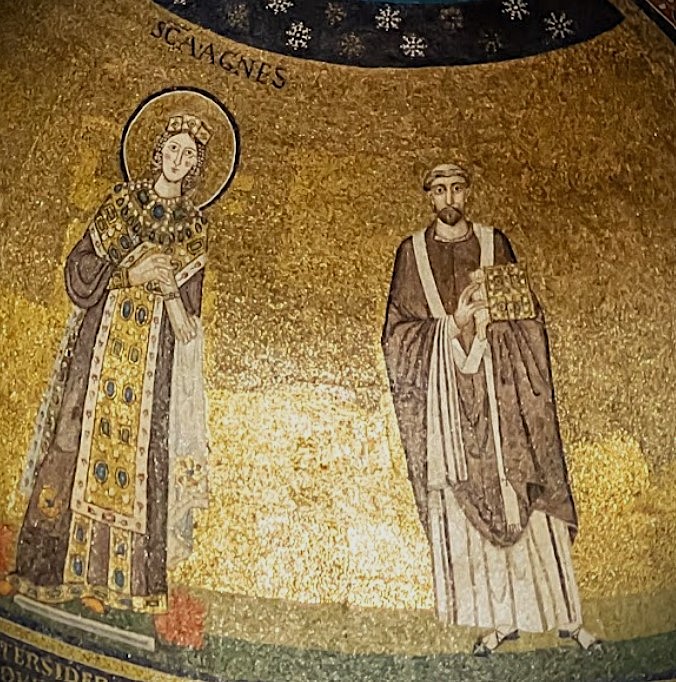

Presumed mosaic of Pope Symmachus in Sant'Agnese fuori le mura, which he commissioned.

Symmachus (Sardinia, mid-5th century – Rome, 514), known for the schism against antipope Laurentius, built or restored several churches. Around 498, he erected (or rebuilt) a church atop an older oratory, dedicating it to the martyrs Pancras (the youth), Pancras of Taormina (a bishop), and Victor. Adjacent clergy baths were constructed near the pagan cemetery above today’s Catacombs of St. Pancras on Octavilla’s land.

Administered by priests of San Crisogono from 522, Gregory the Great later preached his 27th Homily here. Honorius I (625–638) moved Pancras’s tomb—the first recorded translation—and promoted the basilica as a "cemeterial church." Subsequent popes restored it: Adrian I (772–795) added a chapel to St. Victor; Leo X (1513–1521) made it a cardinal titular church.

Severely damaged over centuries, it was rebuilt in 1609 by Cardinal Ludovico de Torres, who demolished the original structure. The Carmelites completed further renovations (1662–1675) under Alexander VII. Bombed in 1849 and restored in 1851, it retains little of its ancient form.

Detail of the basilica’s carved wooden ceiling (1627) and the five-tower coat of arms of Cardinal Ludovico de Torres.

Interior

The simple three-nave church features a 1627 carved wooden ceiling. Stucco reliefs, urns, and paintings (mostly copies) adorn the space. Notable elements include:

• Right nave: 18th-century stucco reliefs of Popes Felix I and II; paintings by Lehoux (1892).

• Main altar: Copy of Palma il Giovane’s The Ecstasy of St. Teresa; porphyry urn with relics of Pancras and Dionysius.

• Apse frescoes by Antonio Tempesta (1555–1630) depicting Pancras and saints, quoting Gregory the Great’s homily.

• Left nave: Lehoux’s copy of Scipione Pulzone’s Crucifixion; remnants of Cosmatesque pulpits (1247).

• Access to the 4th-century catacombs.

Interior of the Catacombs of San Pancrazio.

Catacombs

Originally Coemeterium Octavillae, these are among Rome’s few catacombs never fully lost. Highlights include:

• The "Botrys Cubicle" (late 3rd century), featuring frescoes and a Greek inscription with "christianós."

• Three regions:

1) Below the basilica’s left transept (original entrance).

2) Beneath the forecourt (entrance in right nave).

3) Under the convent (4th-century Constantinian christograms).

The hypogeum spans multi-level galleries with loculi (burial niches) and cubicles carved into tuff.

Piazza di San Pancrazio, 5 (Rome)

Email: segreteria@sanpancrazio.org