Federico Borromeo: The Long Deception of a Cardinal

Milan, Italy

In the seventeenth century, during the Counter-Reformation period, and especially with the establishment of the Inquisition, accusing someone had become far too easy, and the consequences could be very severe. The Inquisition was an ecclesiastical tribunal with broad powers, tasked with investigating and suppressing heresies, meaning beliefs considered contrary to Catholic orthodoxy.

On a sultry mid-August day in 1662, the stories of two men intersect: the famous Cardinal Federico Borromeo (1564-1631) and the clergyman, Latinist, and historian Giuseppe Ripamonti (1573-1643). The former descended from an illustrious family that also included Cardinal Carlo, proclaimed a saint by Pope Paul V in 1610 and made patron saint of Milan; the latter came from a respectable peasant family, which had destined him for a monotonous life as a country priest. However, thanks to his accommodating yet often restless character, once ordained, he managed to embark on a much more prestigious career, living a thoroughly Milanese life in the shadow of Archbishop Federico Borromeo. Indeed, it was Borromeo who examined the young Ripamonti's candidacy and admitted him to the Seminary of the Canonicate in Milan; appointed him as an expert 'historiographer' and granted him access to the College of Doctors of the Ambrosiana; and commissioned him to write the History of the Church of Milan.

Portrait of Giuseppe Ripamonti and Federico Borromeo (1610-1625), attributed to Procaccini (1564-1631)

The Inquisition tribunal issued a sentence against the priest out of hatred, and it was signed by two inquisitors appointed at the Cardinal's behest. Ripamonti ended up in prison for four years (1618-1622), and, after a trial artificially prolonged, was sentenced to an additional three years in prison.

But the strange thing is that the Inquisition, which depended on the Holy Office in Rome, was deliberately kept at a distance, and the case was handled solely by the Milanese Tribunal, which answered to Borromeo. And when the condemned Ripamonti threatened to appeal to Rome, the Cardinal hastened to commute his sentence to a form of supervised release and did not oppose his reinstatement to the religious offices he held prior to imprisonment.

Among the charges brought against him were the content of his work Historia (which he allegedly modified after receiving the Imprimatur), denying the immortality of the soul, conversing with poets and scholars investigated by the Holy Office, reading prohibited books, practicing the infamous crime of sodomy (from which he was, however, acquitted), neglecting religious duties, or even his tardiness at the seminary refectory when he was young. But the reality wasn't quite like that, and Cardinal Federico Borromeo, a man of many resources, managed to disguise it skillfully.

Ripamonti decided to write a letter to a friend, explaining why all this happened after the publication of the first part of his Historia Ecclesiae Mediolenensis (1617):

The true origin of my misfortunes is not what it appears to be; it is because Cardinal Borromeo, having become truly enamoured with the fame of being a Latin writer, and having employed my work for that purpose over a period of ten years, wants me to die before him.

Indeed, while Federico Borromeo is known as the author of an immense series of Latin works of a theological, moral, historical, and erudite nature, Ripamonti seems to unmask the Cardinal's literary fame by asserting that Borromeo never wrote anything in Latin because he wasn't sufficiently skilled in it; so much so that it was Ripamonti himself who meticulously translated for him, from vernacular Italian into Latin, a full twenty volumes. In short, Ripamonti, who dreamt of the thrill of a stay in Spain, would have been a sort of translator for the Cardinal, who, either fearing to lose him or suspecting that he might expose him by telling the truth, wanted to teach him a harsh lesson. And, in effect, the lesson worked because, after his imprisonment ended, his linguistic assistance to the Cardinal continued.

After Federico Borromeo's death, Ripamonti became the "Patriae Historiographer" and wrote De peste (1640) and the Historiae Patriae (1641-43), before passing away in 1643 in Rovagnate, in Lecco. When he died, not even a plaque was placed in the church, but ten years later a marble plaque in Latin appeared, placed in a side chapel of the church, celebrating him as the eleganti rerum patriarum scriptori ("elegant writer of patriotic matters"). Eight years after that, another plaque appeared on the facade of the house where Ripamonti was born. The Provost of the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio had an inscription carved that ended with these words:

He atoned severely within himself for the envy of others and his own eccentricities, comforted only by the patronage of the immortal Federico Borromeo.

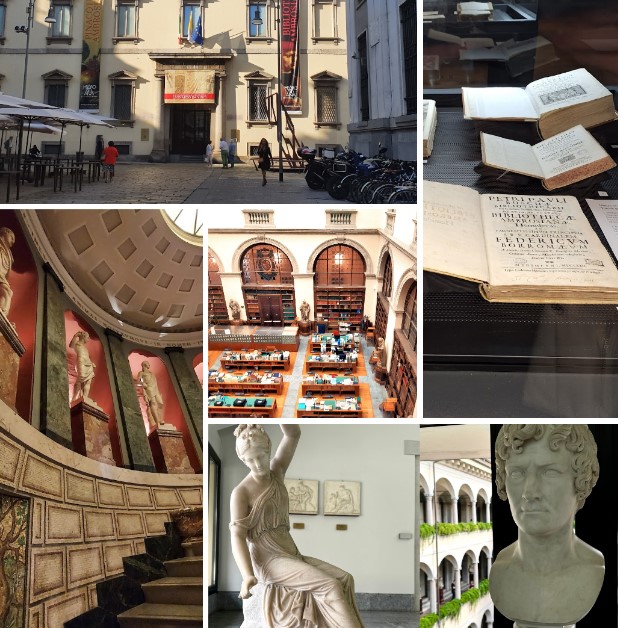

The Ambrosiana Library.

The affair could also be viewed from another angle where there is no hatred, and there is no evil persecutor and a good persecuted victim, but simply a commendable shared project: the Ambrosiana Library. But viewed this way, the recourse to the Inquisition would be unjustifiable.

The Biblioteca Ambrosiana, founded by Cardinal Federico Borromeo in 1607 and inaugurated two years later, was conceived by its founder as a center of study and culture open to anyone who could read and write. Cardinal Federico wanted it to have a multicultural and dialogue-oriented imprint because even books belonging to cultures and faiths different from the Christian one "can bring various benefits and make us aware of many beautiful and highly useful things."

To this end, Borromeo proposed establishing a college of about fifteen learned clergymen, whose task would be to specialize in various branches of knowledge to better contribute to the glory of the Church, the defense and propagation of the faith, and the benefit of scholars. This college was maintained and financed personally by Borromeo so that its members could pursue their studies without material concerns. Among them was Ripamonti, who held the function of Scriptor Latinus(Latin Writer), and to be one, he necessarily had to have excellent skills as a Latinist, while Borromeo was the project's designer and had to ensure it was realized to the best standard and within a reasonable timeframe.

Borromeo also took care to ensure the institution's continuity after his own death by leaving a reserve endowment. If this did not adequately meet the need, it was not for lack of goodwill on the founder's part, but due to the calamities of the times, particularly those occurring in the final period of his industrious life, during which he found himself forced to allocate large sums to aid his diocesans, who were terribly afflicted by wars, plague, and famine.

Piazza Pio XI, 2, (Milan)