The Hypogeum of Cristallini: A Rare Glimpse into the Hellenic Soul of Ancient Naples

Naples, Italy

In 1889, Baron Giovanni di Donato, while searching for a water source beneath the basement of his family palace, decided to dig more than ten meters deep. To his astonishment, he uncovered an ancient treasure of Hellenic painting and architecture buried for over 2,300 years. It was a Greek-era hypogeum dating back to the first half of the 4th century BCE: skeletons and skulls in four ancient chamber tombs, among the most beautiful of the ancient world, preserved intact to this day. These tombs featured lavishly painted halls, decorated and furnished with over 700 funerary objects, mostly terracotta vessels used for libations during rituals, as well as realistic reproductions of fruit like pears, pomegranates, and eggs—all symbols of rebirth after death.

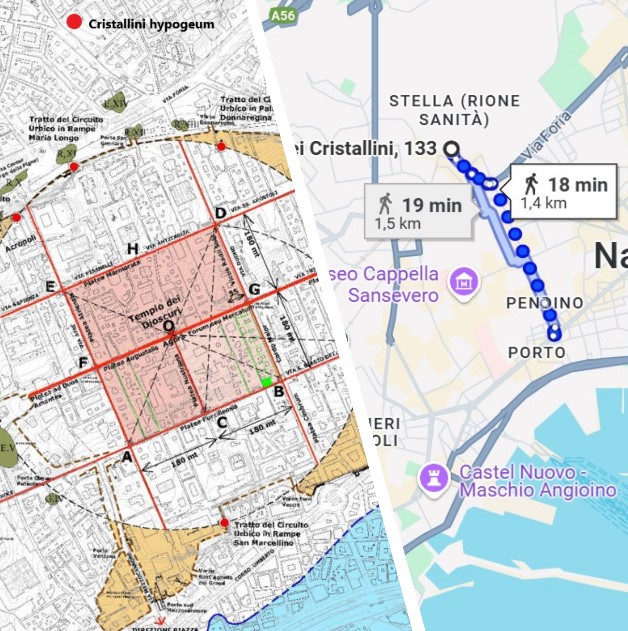

The Baron cleared the tombs of accumulated silt, had the skeletons removed and reburied elsewhere, handed over the recovered funerary artifacts to the city’s Archaeological Museum, and sealed the tombs for safekeeping. For over 130 years, his descendants chose to protect and keep this sacred site closed—until 2022, when, after extensive restoration, it was reopened to the public. The hypogeum is one of the best-preserved relics of ancient Greece in the world. It lies beneath Palazzo di Donato at Via dei Cristallini 133 in Naples, in the Rione Sanità district.

The Hypogeum of the Cristallini - At the center of the image, a child's face, crafted in plaster and wax, by Christian Leperino (2022)

This neighborhood occupies a valley used since Greco-Roman times as a burial ground, corresponding to the area north of the ancient Greek city of Neapolis. The profound connection between man and death in this place stems from its salubritas —both natural, due to its abundance of woods and water springs, and supernatural, as it housed catacombs believed to be responsible for inexplicable healings and miracles following prayers to the dead in its many cemeteries. Over time, the area has hosted not only Hellenistic hypogea and Paleochristian catacombs but also a 15th-century plague quarantine and a cemetery for victims of the great 1656 pestilence.

The Greeks of the first half of the 4th century BCE, who inhabited the city, were still part of Magna Graecia. They constructed several funerary hypogea, underground tombs where the remains of ancient Neapolitans rested for millennia. Today, six meters below street level, beneath Naples’ palaces and alleyways, lies an invaluable historical and artistic heritage.

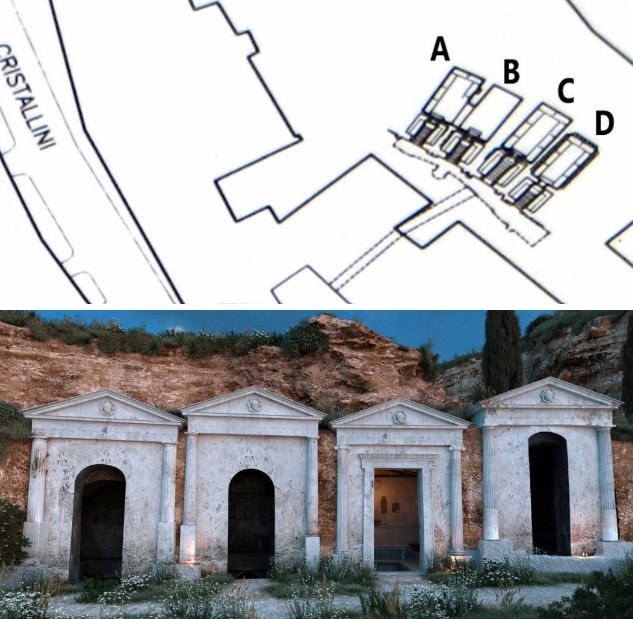

The tombs of the Hypogeum of the Cristallini were adjacent, each with an independent entrance, and must have had imposing sculpted façades, complete with Ionic columns and street-level doors leading directly to the burial chamber—covered by barrel vaults and accessed via a stepped dromos. Here, funeral rites could be performed directly above the actual tomb. Alternatively, in larger monuments, there were two superimposed chambers: an upper room, opening to the lower one, which featured a bench along the walls and a trapeza (offering table) on the rear wall for funeral ceremonies.

How the Four Tombs Originally Appeared (Externally Accessible from Street Level)

The Four Tombs:

Hypogeum A: Adorned with eight bas-reliefs, time and human extraction of stones from the underground largely destroyed its structure, leaving only one bas-relief intact.

Hypogeum B: This tomb preserves a treasure of amphorae, artifacts, urns, altars, and frescoes—a fully furnished hypogeum where time seems to have stood still.

Hypogeum C: The largest and most extraordinarily well-preserved tomb in the group. Today, it is accessed via a striking ten-meter-long stone staircase.

• Upper Chamber: The walls feature three floral wreaths of different types. The entrance wreath depicts a myrtle branch supporting a garland of flowers and ribbons, similar to those on the lower chamber’s rear wall. A painted frieze runs along the upper walls and the sides of the entrance and passage pediments: triumphant griffins with spread wings alternate with floral motifs and small male and female heads, with dark green apophyses atop them.

Lower chamber of Hypogeum C, virtually restored (the third hypogeum). Note the sarcophagus-beds carved into the tuff rock, resembling klinai, complete with sculpted mattresses and double pillows, painted in yellow, purple, light blue, and red.

• Lower Chamber: Along its three sides stand eight magnificent kline-sarcophagi (empty inside and covered with terracotta slabs), carved into tuff with sculpted mattresses, double pillows, and painted feet replicating 4th-century BCE throne-leg decorations documented in Macedonia.

A dentil cornice crowns the walls, where terracotta pomegranates and pears were originally placed, and a bronze lamp once hung from the vault’s center.

The vivid and rare colors used in the refined paintings (madder red, Egyptian yellows, and blues) attest to the deceased’s wealth, as only the affluent could afford such luxurious furnishings. Their names are scribbled in ancient Greek beneath the garlands.

Hypogeum C, lower level: Medusa's head

Among the decorations, the head of Medusa and the scene of Dionysus and Ariadne stand out.The Medusa in the lunette on the rear wall likely served an apotropaic function—warding off evil with her powerful gaze.

Hypogeum C, lower chamber – entrance wall: Depiction of Ariadne and Dionysus in a nuptial scene

Meanwhile, Dionysus and Ariadne are depicted reclining opposite each other in a nuptial pose: the youthful, semi-nude male figure holds a thyrsus, while the female figure, with traces of drapery, raises her left arm. This scene is rich in symbolism: Ariadne, abandoned by Theseus, is consoled and beatified by the god’s love, sharing in the gift of immortality.

It is plausible that the hypogea of Neapolis originally housed members of the urban elite involved in the wine trade, alluded to by Dionysian worship.

Roman-era burials

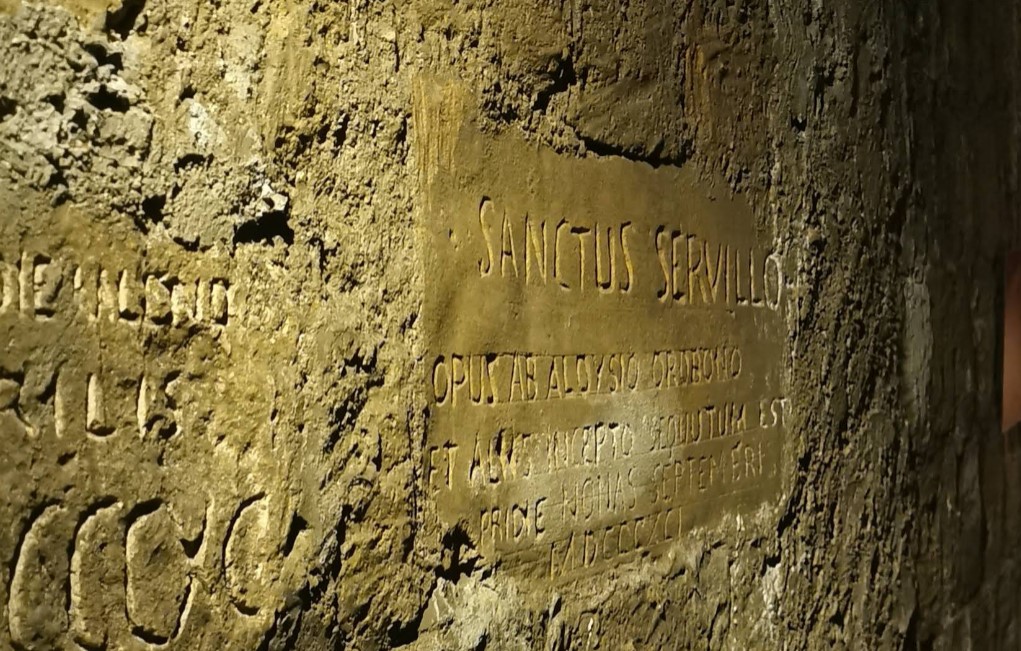

Hypogeum D: Significantly modified in Roman times, its walls feature niches and sculpted reliefs not from the original Greek tomb but from its reuse for later Roman burials, which continued until the 1st century CE, when landslides filled all the tombs. The artifacts and treasures found inside are Roman-era, including a Latin inscription. While all four hypogea share similar interior structures, only this tomb contains painted and inscribed marble stelae.

Greek Neapolis

Origins of Greek Naples:

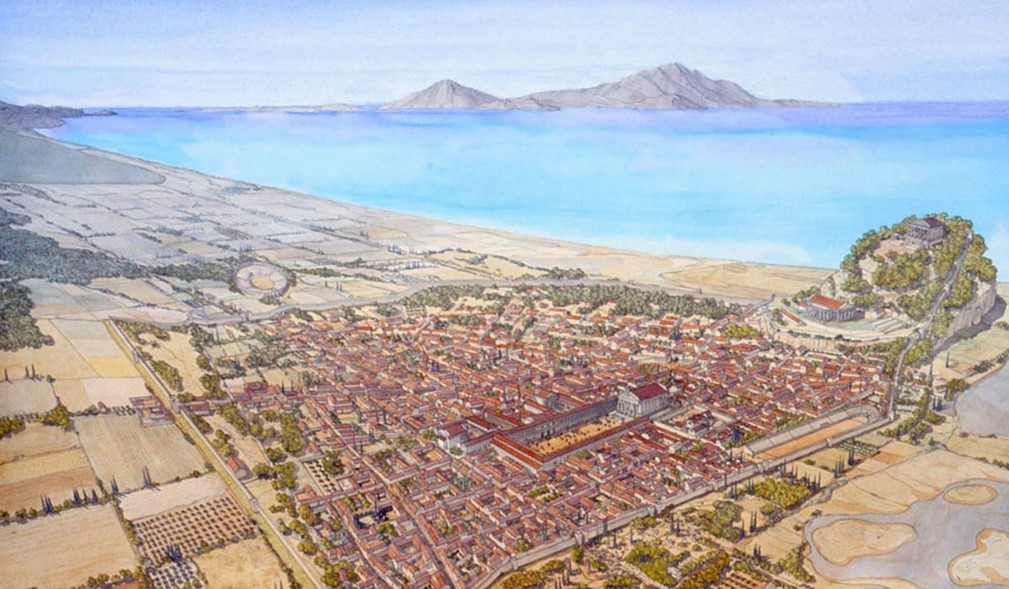

According to the Greek philosopher and historian Strabo (c. 60 BCE–24 CE), the colonization of Magna Graecia—as the Romans called the Hellenized coasts of Campania, Basilicata, Apulia, Calabria, and Sicily—began during the Trojan Wars and lasted centuries due to demographic pressures, famines, civil wars in Greece, and the need for new trade outlets.

The Euboeans founded the first colonies in Campania: Pithekoussai on Ischia and Kýme (Cumae, meaning "wave," referencing the peninsula’s shape) on the mainland. However, growing archaeological evidence suggests Mycenaean trading posts operated in southern Italy centuries earlier. Kýme was indeed the first Greek colony in the West, established in the late 8th century BCE by Euboean-Chalcidians from Pithekoussai.

Kýme or Cumae

By the mid-7th century BCE, Rhodian sailors founded a colony less than 20 km from Kýme, between the islet of Megaride (now Castel dell’Ovo) and Monte Echia hill (Pizzofalcone). They named it Parthenope after the famed siren. Legends surround Parthenope—the most credible claims she was among the sirens who failed to enchant Odysseus and, heartbroken, threw herself into the sea; her body washed ashore at Megaride.

Island Pithekoussai, Kýme and Neapolis

After 5th-century BCE attacks by Italic neighbors, internal strife, and malaria, most Greek colonies declined. In 514 BCE, Parthenope’s economic downturn began due to conflicts between Etruscans and Cumaeans. It is unclear whether the city was abandoned or continued on a smaller scale. After 474 BCE (the Second Battle of Cumae), Cumaean and Syracusan forces defeated the Etruscans, and Greeks repopulated Parthenope, renaming it Palaepolis ("Old City").

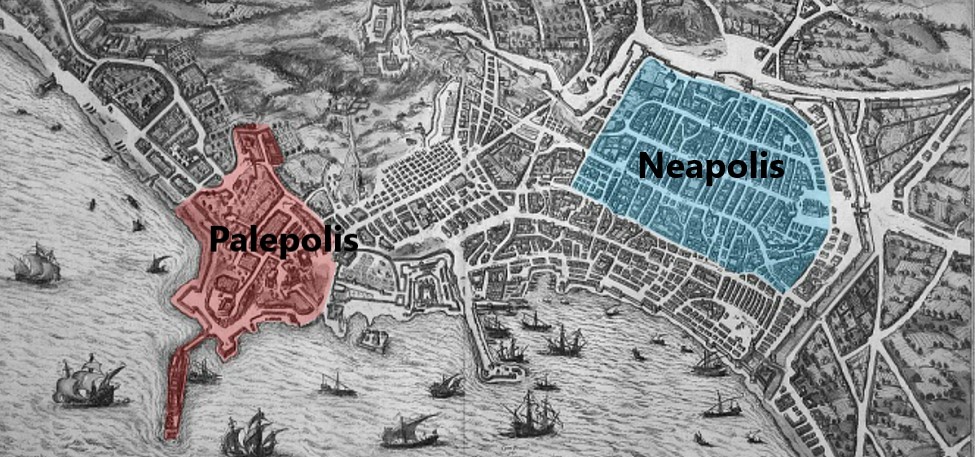

Palaepolis and Neapolis

Around 470 BCE, the Cumaeans founded a new city 1.5 km from Palaepolis: Neapolis ("New City"), the first true urban center, fortified with a small port. Rapid growth followed, aided by Syracuse’s decline and strong ties to Athens.

Naples thrived in pottery, crafts, and agriculture, becoming a commercial hub between Greece, Magna Graecia, and the Italic hinterland (Samnites and Etruscans). In 421 BCE, Italic peoples conquered Capua and Cumae but spared Neapolis, which absorbed their influence.

In the late 4th century BCE, Neapolis allied with Italic peoples against Rome but was defeated after a long siege. However, Rome granted favorable terms (foedus aequum), allowing autonomy. Prosperity followed, despite competition with Puteoli’s port.

In 327 BCE, Neapolis became the first Greek city in Italy absorbed by the Roman Republic. Though hard to imagine today, it remained a Graeca urbs in essence until the 1st century CE, with Greek spoken until the 3rd century CE—when Christian persecutions ended and churches, some commissioned by Constantine, emerged.

A rare testament to Neapolis’ unique Hellenic identity, amid the near-total loss of Greco-Samnite monumental evidence, are painted chamber tombs like those on Via dei Cristallini. Built between the late 4th and mid-3rd centuries BCE, these were once above ground with monumental rock-cut façades, later buried by landslides, now hidden beneath Naples’ bustling streets.

Naples, Via dei Cristallini 133

Email: info@ipogeodeicristallini.org