Gaddi-Cesi Palace: Renaissance Splendour and the Shadows of History

Rome, Italy

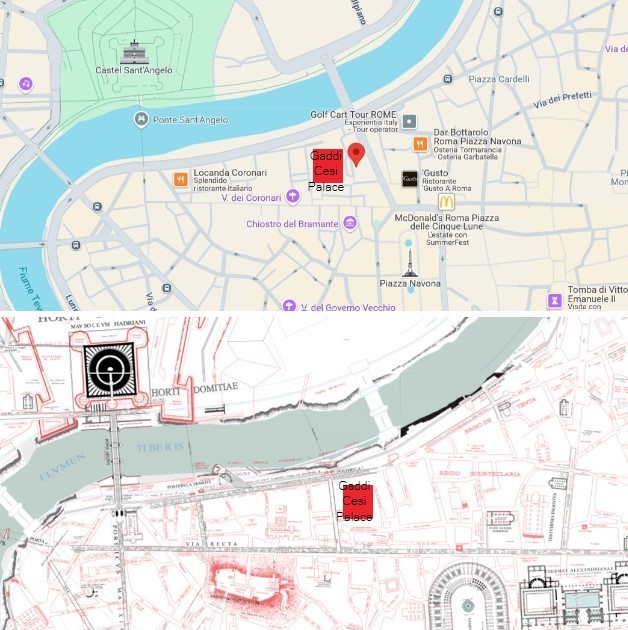

Beyond Castel Sant'Angelo, on the opposite bank of the Tiber River, stands 'Gaddi's Palace'. It earned this name after being built in the early 16th century for the wealthy Florentine merchant and banking dynasty of the same name.

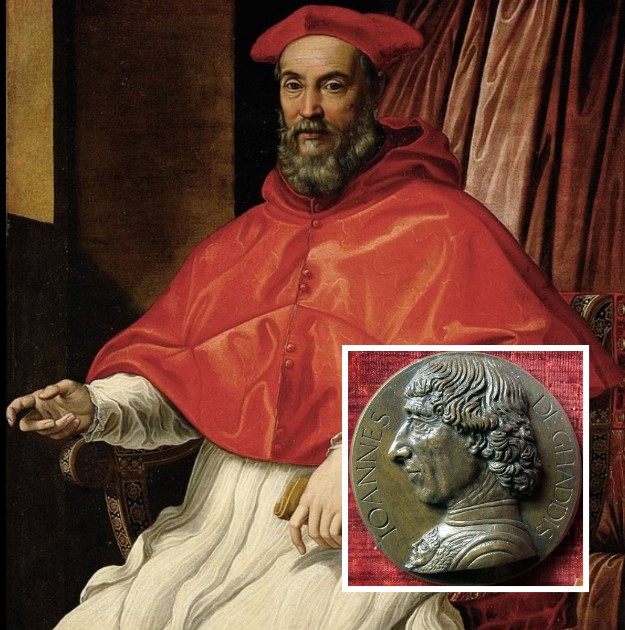

While the Florentine branch of the family was primarily a renowned dynasty of painters active between the 13th and 15th centuries—including a pupil of Cimabue and Giotto’s principal assistant—the Roman line was distinguished by cardinals like Monsignor Giovanni Gaddi (1493–1542), Dean of the Apostolic Chamber Clerics, who financed the printing of Machiavelli’s Discourses (1531) and The Prince (1532). His brother Cardinal Niccolò Gaddi (1499–1552), a famed antiquarian collector, acted as an agent for Grand Duke Francesco I de' Medici, acquiring bronzes, coins, and paintings.

Portrait of Niccolò Gaddi by Jacopino del Conte and medal of Giovanni Gaddi, Florentine School (c. 1480–1510)

After seeking refuge in Rome in 1536, the Gaddi regained Medici favor. They secured extensive privileges and expanded their operations during the papacies of Medici Popes Leo X and Clement VII, who favored their Roman banking house over rivals. Amid exceptional financial demands, the practice emerged of selling offices and outsourcing state revenues to bankers. The Gaddi bank even handled payments for papal artists, including Michelangelo—while working on Florence’s San Lorenzo Sacristy, he was paid by Clement VII through the Gaddi bank.

The Sack of Rome (1527) and Clement VII’s death severely damaged Florentine bankers in the Curia, many of whom saw their credits erased. Though the Gaddi suffered losses, they swiftly recovered.

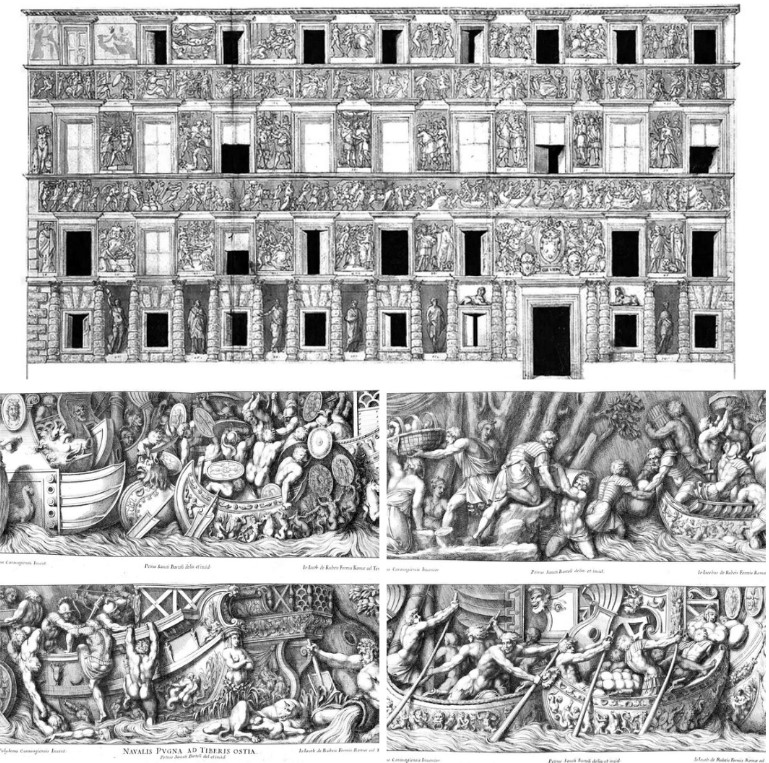

Designs of façade decorations by Polidoro da Caravaggio and Maturino da Firenze for Gaddi's Palace, held at Vienna’s Albertina Museum

Gaddi's Palace featured exquisite chiaroscuro paintings and sgraffito on its façade facing Via Maschera d’Oro. Vasari described them as

executed with such grace and skill that the eye is lost among the wealth of beautiful inventions

These works—including The Rape of the Sabine Women—were created by Raphael’s pupil Polidoro da Caravaggio (1499–1543) and Maturino da Firenze (1490–1528), artists active across Rome. Over time, the deteriorating frescoes were whitewashed. Lesser-quality decorations by the same artists survive on the nearby Palazzo Milesi (see street view below).

Portrait of Marquis Pier Maria Rossi (1535–1538) and Camilla Gonzaga with three of their ten sons (c. 1539–1540) by Parmigianino. Likely Troilo, Ippolito, and Federico. — Prado Museum, Madrid.

Shortly after its construction, the palazzo was acquired by the noble de’ Rossi family of Parma, one of Emilia’s most influential Renaissance dynasties. Notable descendants of General Count Pier Maria III de’ Rossi (1504–1547) and Camilla Gonzaga (1500–1585) include: military commander Troilo II (1525–1591), who accompanied Cosimo I de’ Medici to Rome in 1570 to receive the title of Grand Duke of Tuscany from Pope Pius V; Cardinal Ippolito de’ Rossi (1532–1591), who participated in the 1590 conclaves electing Pope Urban VII (13-day papacy) and Gregory XIV (Niccolò Sfrondati)—weakened by consecutive conclaves, Ippolito died of malaria; and condottiero Sigismondo (1524–1580), who served Cosimo I.

Acquasparta (Terni) and Cesi's Palace

In 1567, Sigismondo de’ Rossi sold the palazzo to Angelo Cesi (1542–1570), after whom it became "Cesi's Palace." Angelo, son of Giangiacomo Cesi and Isabella d’Alviano, descended from Umbria’s ancient Cesi family—which produced five cardinals—originating near Terni and Acquasparta (a town likely of Roman origin, ad Aquas Partas ["between divided waters"]). At Acquasparta, the family replaced their fortress with the namesake palace (16th century). Following his father, Angelo became a decemvir in Todi and served the Papal States militarily. In 1569, under Pius V, he commanded troops aiding Charles IX against Huguenots in France, distinguishing himself at Poitiers before dying in 1570.

After Angelo’s death, the palazzo was leased to Ugo Boncompagni—elected Pope Gregory XIII in 1572—before reverting to the Cesi..

Santa Maria della Pace (Rome) – Cesi Chapel – Reliefs by Simone Mosca. Cesi-Salviati coat of arms above the portal at 21 Via della Maschera d’Oro, Rome

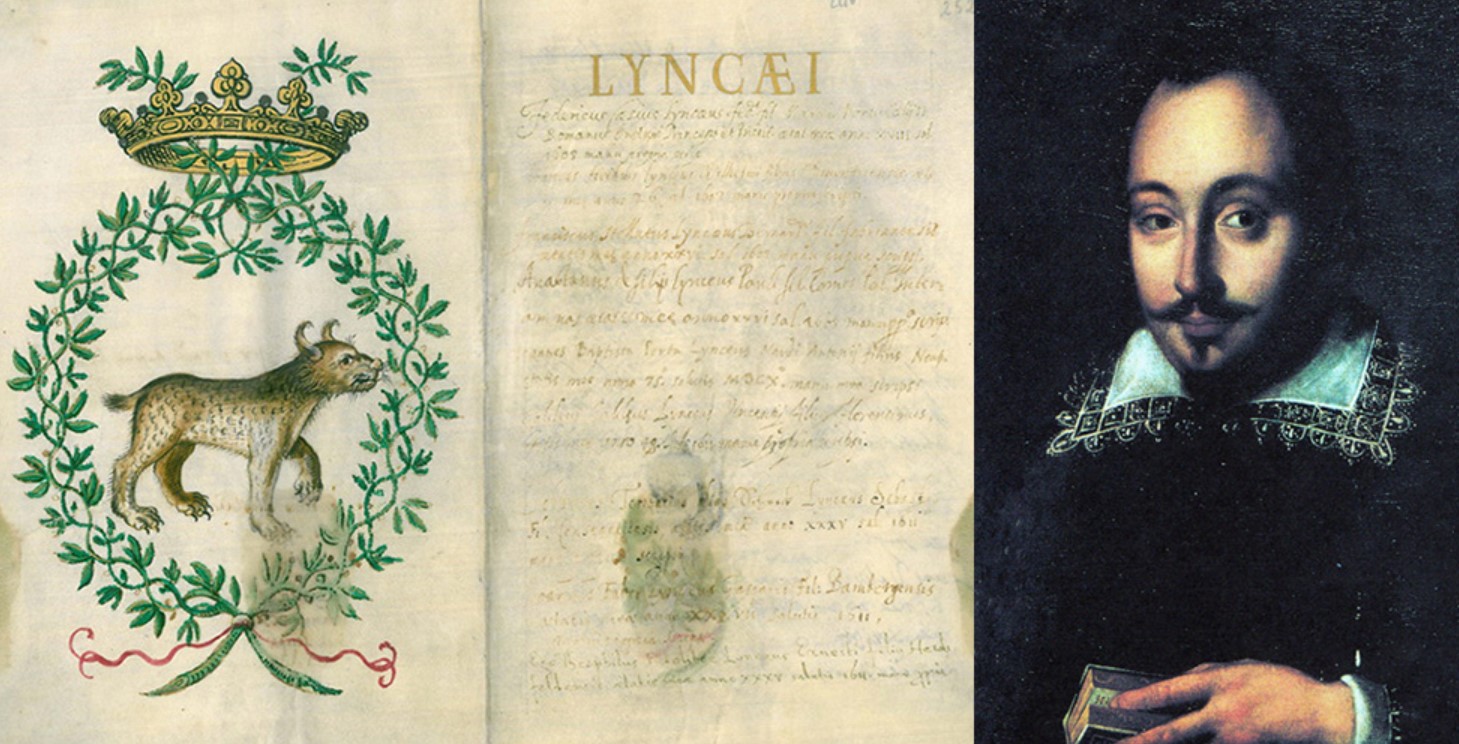

The Cesi family’s most illustrious member was Angelo’s great-great-nephew Federico (1585–1630). A vibrant polymath, he pioneered biological research in his Rome palazzo’s gardens (transformed into a botanical garden where two Thracian King statues—later bought by Clement XI—now in the Capitoline Museums were found). Initially supportive, his parents grew impatient with his studies. At 18, he founded the Accademia dei Lincei (Academy of the Lynxes), one of Europe’s oldest scientific institutions. Named after the mythological sharp-sighted Lynceus, symbolized by a lynx, its observational ethos revolutionized knowledge. Based first at Cesi's Palace in Acquasparta, it hosted Federico’s close friend Galileo Galilei (member from 1611). Federico leveraged his patrician influence to defend Galileo against ecclesiastical authorities.

First emblem of Rome’s Accademia dei Lincei and portrait of Federico Cesi by Ragazzini (Palazzo Corsini, Rome)

Born at Cesi's Palace, Federico returned after marrying Isabella Salviati—hence the Cesi-Salviati coat of arms still crowning the portal at 21 Via della Maschera d’Oro. A plaque on the façade (1872) commemorates:

Prince Federico Cesi, Roman, who, beset by malicious persecutions, kept the flame of science alive. An illustrious naturalist, founder of the Accademia dei Lincei, he hosted its learned assemblies and his friend Galileo in this family palace.

The "malicious persecutions" began in 1615 when Dominicans denounced the Lincei as a pro-heliocentric sect. This culminated in Galileo’s infamous 1633 condemnation. After Federico’s death (1630), his wife liquidated his library, natural history museum, and botanical garden. Fearful of persecution post-Galileo, the Lincei disbanded. The Academy only revived in 1847 as Pius IX’s Pontificia Accademia dei Nuovi Lincei (now the Pontifical Academy of Sciences).

Colossal seated statue of Roma from the Cesi Collection, Hadrianic period (117–138 AD), after a 5th-century BC Greek original. Juno Cesi (female statue), 2nd century BC, New Palace, Capitoline Museums, Rome. Its high quality and parallels with Pergamene sculptures suggest a Pergamene original. Entered the museum in 1733 from the Cesi Collection.

Wealthy Roman families competed to collect prized antiquities. The Cesi, famed for their passion, amassed a significant sculpture collection—so renowned it featured in 18th-century Rome guidebooks. Some works remain in situ; others are in Palazzo Altemps or the Capitoline Museums.

Vase or krater with Bacchic scenes, known as the 'Tazza Cesi' (Cesi's Cup)"

This krater—elegantly carved with Bacchic symposium scenes, resting on lion paws—likely adorned Agrippina Major’s Horti (imperial gardens stretching from the Janiculum to the Vatican). Used as a fountain alongside a Silenus statue in antiquity, it later stood near Trastevere churches before entering the Cesi Collection in the 16th century. Acquired in the 1800s by Alessandro Torlonia for his Via della Lungara museum.

Among Rome’s most celebrated Renaissance antiquities collections, the Cesi Collection began in the early 1500s under Cardinal brothers Paolo Emilio (1481–1537) and Federico Cesi (1500–1565) near St. Peter’s. Paolo lost everything in the 1527 Sack of Rome. Dispersal was swift and total—by the 1700s, little remained of their Vatican statuary.

Location of Gaddi's Palace-Cesi in Rome’s stratigraphic map of archaeological heritage uncovered in known excavations.

Later, the palazzo changed hands repeatedly: In 1798, Marquis Ulisse Pentini housed the Depositeria Urbana (Urban Deposit Office, founded by Urban VIII in 1629 for judicial pledges); it passed to Baron Camuccini (son of painter Vincenzo), then in 1855 to the Duke of Northumberland, followed by the Santarelli family, and finally Salvatore Buffardi (1929).

On October 16, 1943—Sukkot, when Jews rested at home—Nazis raided Rome’s Ghetto and beyond. 1,259 people (689 women, 363 men, 207 children) were torn from their homes. While 227 from mixed families were released, over 1,000 Roman Jews were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Only 16 survived (15 men, 1 woman). No child emerged alive.

Expropriated in 1940, the palazzo became—and remains—home to the Military Tribunal. It gained notoriety in 1994 when the "Cabinet of Shame" was discovered during investigations into SS Captain Erich Priebke. This cupboard, long hidden facing a wall, contained "temporarily archived" documents: 695 files and a General Register listing 2,274 war crimes committed in Italy (1943–1945) by Nazi-Fascist forces. These included major atrocities like Sant’Anna di Stazzema, the Fosse Ardeatine, Marzabotto, Monchio, Cervarolo, Korytsa, Leros, and Scarpanto.

Collected over years and shelved in 1960, the files remained secret until found. Despite their discovery, they stayed classified until 2016, when Italy’s Chamber of Deputies lifted state secrecy and published them online (https://archivio.camera.it/), unveiling one of Italy’s darkest chapters.

Rome, Via degli Acquasparta, 2 or Via della Maschera d'oro, 21