The Acciaiuoli: Bankers, Builders, and Patrons of Florence’s Golden Age

Florence, Italy

From the medieval turmoil of Italy emerged the Acciaiuoli—a name that would resonate through the corridors of power, finance, and art. Their story begins with Guigliarello Acciaiuoli, a Guelph exile fleeing political persecution in Bergamo around 1160, seeking refuge in Florence, the burgeoning heart of Tuscan commerce.

Palace of Vicars at Certaldo (Florence), coat of arms of the Acciaiuoli family

The Origins of a Dynasty

The Acciaiuoli (also spelled Acciaioli, Acciajuoli, Accioli, Acioli, or Accioly) were an influential Italian banking family. According to legend, the patriarch Guigliarello Acciaiuoli fled Bergamo due to political persecution against the Guelphs, a faction he supported, and settled in Florence around 1160.

The Guelphs were a medieval Italian political faction that championed the Pope's authority over the Holy Roman Emperor. Their centuries-long rivalry with the Ghibellines, who backed the Emperor, profoundly shaped Italian politics from the 12th to the 14th centuries.

The Acciaiuoli were popolani (commoners). Their surname likely derives from acciaio (steel), suggesting involvement in the steel trade. It is worth noting that Italian surnames emerged in the Middle Ages. Before the year 1000, individuals bore only a single name, though some documents included a baptismal name and a nickname. After the turn of the millennium, nobles adopted family names tied to their ancestral castles (e.g., Firidolfi of Meleto), while urban nobles identified with their residences (e.g., the Donati tower in Florence). Commoners, however, distinguished themselves by occupation (e.g., Bartholomew the blacksmith), patronymics (e.g., Bartholomew son of Michael), or their village of origin (e.g., Bartholomew from Vinci). Farmers often took names reflecting the land they cultivated.

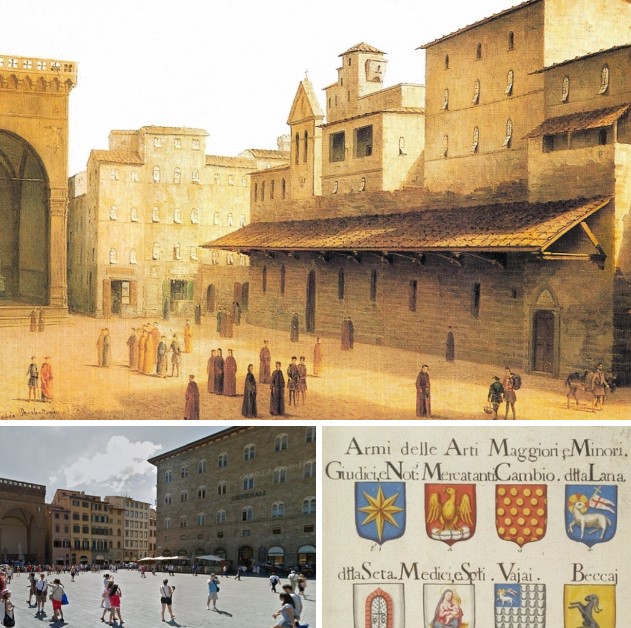

Emblems of the major and minor Florentine Arts (AS Firenze, Fondo Manoscritti, 471, c. 13, XVIII century) The third emblem on the top is those of the Art of Exchange (Cambio). View of Ancient Florence by Fabio Borbottoni (1820-1902), 1850. The destroyed canopy of the Pisans that covered the seat of the Art of Exchange, on the right, and how it looks like today.

Guigliarello Acciaiuoli enrolled in Florence’s Arte del Cambio (Guild of Moneychangers). These guilds, established across European cities from the 12th century onward, regulated and protected trades. Though termed "corporations" only in the 18th century, they were known as métiers in France, guilds in England, and arti in Florence or scuole in Venice. The Arte del Cambio, founded around 1202, united moneychangers, dealers in precious stones and metals, and bankers handling deposits and credit. By 1352, its headquarters stood in Piazza della Signoria under the Loggia dei Pisani (later demolished in the 19th century; today, the site hosts the Palazzo delle Assicurazioni Generali).

Rise to Prominence

Post-1000, commerce’s growing importance granted Italian cities political autonomy, transforming them into independent city-states governed by elected councils. Merchants, as the economic and political backbone, occupied central roles. The Acciaiuoli swiftly ascended to become one of Florence’s most powerful families, participating actively in politics as Priors, Gonfaloniers of Justice, and Consuls of the Guilds. Notably, as bankers, they had maintained economic ties with the Church since the Middle Ages.

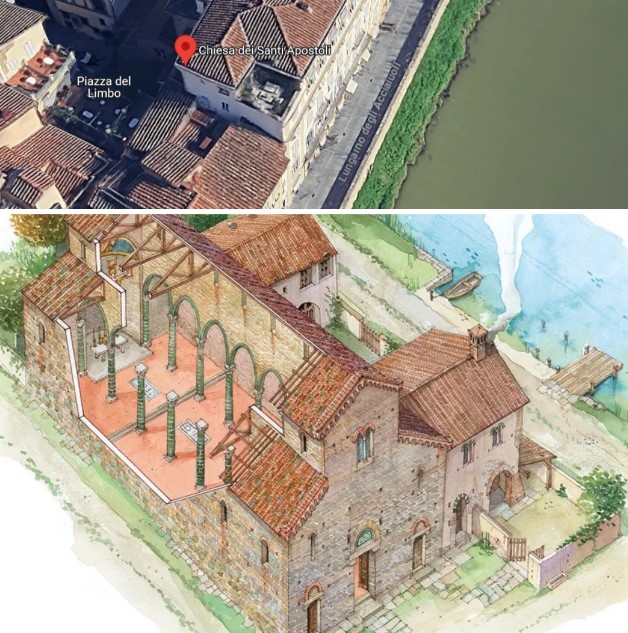

The Church of the Holy Apostles today, and a hypothetical reconstruction of it in the Middle Ages and highlights the its vicinity to the Arno river; an aspect that isn’t gathered easily, since the church, due to its small size, is almost partly hidden by the modern buildings of the Lungarno.

Guigliarello settled in Borgo dei Santi Apostoli, within Florence’s Santa Maria Novella district. The area’s Romanesque Church of Santi Apostoli (11th century) stands near Lungarno Acciaioli, facing Piazza del Limbo—a medieval cemetery for unbaptized infants, believed to dwell in limbo (limbus). Dante reputedly drew inspiration from this site for his Inferno’s Limbo (Canto IV).

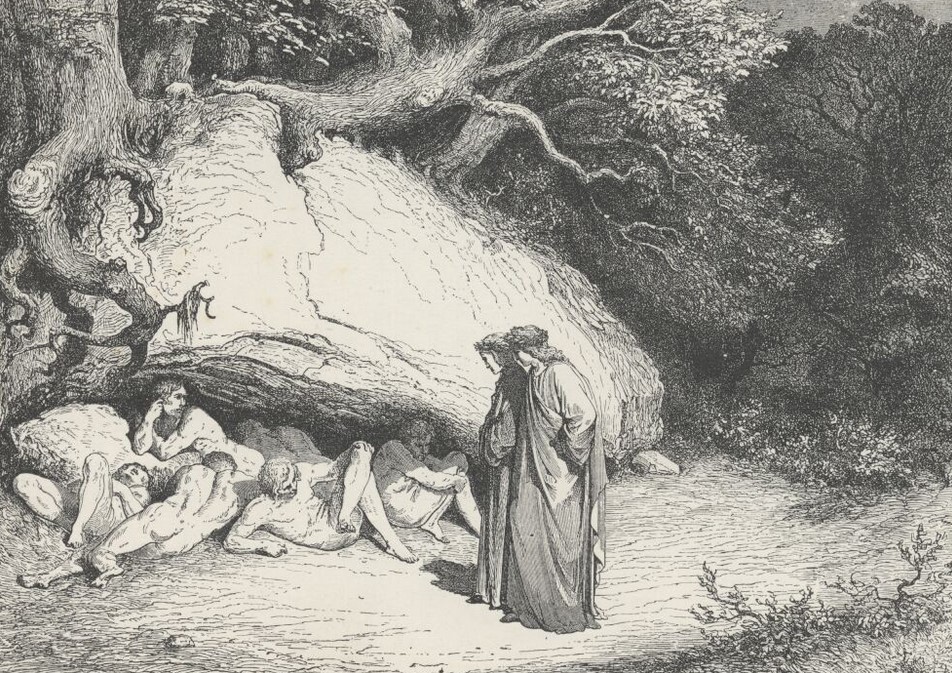

'Only so far afflicted, that we live / Desiring without hope.' (Inferno, Canto IV, lines 38,39). An illustration of Gustave Doré (1832 – 1883). Plate XI: Canto IV: The Virtuous pagans.

Dante is borne across the river Acheron in his sleep, and awakes on the brink of the dolorous valley of the abyss. He enters the First Circle of the Inferno; the Limbo of the Unbaptized, the border land, as the name denotes.

There, as it seemed to me from listening,

Were lamentations none, but only sighs,

That tremble made the everlasting air.

And this arose from sorrow without torment,

Which the crowds had, that many were and great

Of infants and of women and of men.

To me the Master good: “Thou dost not ask

What spirits these, which thou beholdest, are?

Now will I have thee know, ere thou go farther,

That they sinned not; and if they merit had,

’Tis not enough, because they had not baptism

Which is the portal of the Faith thou holdest;

The Church of Santi Apostoli, nestled between Ponte Vecchio and Piazza della Repubblica, was once outside the city walls. Despite never serving as a cathedral, Florentines dubbed it the "Old Duomo" for its antiquity and significance. The Acciaiuoli, among other prominent families, funded its restorations and buried their dead beneath its floors.

Eucharistic tabernacle (ca 1512) by Andrea Della Robbia, on left. Around 1512, Giovanni Acciaiuoli commissioned Andrea della Robbia to do the Eucharistic Tabernacle in polychrome glazed terracotta for the Church of the Holy Apostles. The tabernacle was placed on the left aisle of the church, above the tomb of Donato Acciaioli the old (?-1333), great-grandson of Gugliarello, which was made by an unknown sculptor in 1333. Giovanni Acciaiuoli (1460-1527) - son of Pietro - participated actively in political life of his city, and was a bitter opponent of Medici. He died of plague in Florence in 1527.

The tombstone of Leone Acciaiuoli (Ortona, 1220 ca. – Florence, 1300) in the Church of the Holy Apostles, Florence. He was a Gugliarello's son and become a famous sailor: he reached the island of Chios by three galleys and brought to Ortona the relics of the Apostle Thomas, during 1258. Chios was considered the island where the Apostle Thomas, after his death in India, had been buried.

Legacy and Decline

The family erected towers and palaces in Borgo dei Santi Apostoli. Their riverside palace on Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli, destroyed by retreating German troops in 1944, once overlooked the Arno. Only their medieval-style palace at 9 Via Borgo dei Santi Apostoli remains, originally built by the Buondelmonti (c. 1280) and acquired by Niccolò Acciaiuoli in 1341.

A detail of palace at 9, via Borgo dei Santi Apostoli, the Certosa plaque, and a fresco of Niccolò Acciaiuoli by Andrea del Castagno in the Uffizi.

Niccolò (1310–1365), Grand Seneschal of Naples and friend to Petrarch and Boccaccio, expanded the family’s 13th-century bank (Compagna di Ser Leone degli Acciaioli e de’ suoi consorti), with branches from Greece to Western Europe. As papal bankers, the Acciaiuoli amassed vast influence. Niccolò commissioned the Florence Charterhouse (Certosa del Galluzzo), where he was interred.

The Charterhouse, begun in 1341, became a sprawling monastic complex consecrated in 1395. Modeled after France’s Grande Chartreuse, it housed Carthusian monks until 1810, endured looting, and was later occupied by Cistercians (1958). Its design even inspired architect Le Corbusier.

Florence Charterhouse, Florence, Italy. Monastery: overview from Le Gore (Via Volterrana)

The family’s fortunes waned after King Edward III of England’s defaults triggered their bank’s collapse in 1345. Though they retained some influence, their prestige never fully recovered. The dynasty fragmented, with branches spanning the Mediterranean, England, France, Germany, and Greece, before dying out in 1834.

The Acciaiuoli's story is one of rise and ruin—a testament to how wealth, power, and patronage could shape a city’s destiny, only to be reclaimed by time.

All things must pass, even the greatest fortunes.

A lesson etched in the stones of Florence.

Florence, Via Borgo dei Santi Apostoli, 9