The priest and the house of the giants

Barletta-Andria-Trani, Italy

Angelo Mosso (Turin, 30 May 1846 – Turin, 24 November 1910) was an Italian physician, physiologist, and archaeologist, but is also remembered as the inventor of the first sphygmomanometer, still in use to measure blood pressure.

In 1909, a farm overseer (massaro) had a conversation with the priest Francesco Samarelli about a stone hut located on his master's land. Samarelli immediately advised Mosso, an archaeologist and senator of the Kingdom of Italy. After an initial reconnaissance at the farm of Lucietta Pasquale Berarducci of Bisceglie on August 3, the priest and the senator slowly reached the site on August 9. They were accompanied by na incessant rain and walked on country roads with their feet sinking into the mud. But in the end, they sighted the dolmen. It was still intact and hidden by olive trees. For Mosso, it capped off his archaeological expeditions, and he always remembered it as one of the most beautiful days of his life. They also noticed piles of stone and soil covering the structure and realized that local farmers had already removed material before their arrival. Nevertheless, the excavations carried out inside the burial chamber returned numerous human bone remains dating back to 1200-1000 BCE, ox bones mixed with ashes and coals (undoubtedly the leftovers of funeral banquets consumed in honor of the dead), and a rich funerary kit consisting of small vases, necklace pendants, a spindle whorl (fusaiolo), fragments of an obsidian blade and flint, and a bronze phalera; while in the dromos, some crockery, blackened perhaps by ritual fires, and a jug were found. The discovery received significant coverage in the national press.

On the left Abbot Francesco Samarelli and on the right Senator Angelo Mosso

Some indications suggest that the Chianca dolmen was used for the practice of elaborate rites of passage:

• The burial chamber (a symbolic representation of the otherworldly dimension) contained dishes as well as animal bones, which ideally served as sustenance for the journey. In this sense, the dromos served as an anteroom for the funeral banquet.

• The dromos (ideally the path the soul of the deceased had to take to reach the afterlife) is oriented towards the east, where the sun rises, where the day begins, and thus life.

• The fires lit along the corridor were perhaps intended to facilitate the transit of the deceased.

• The holes visible at the level of one of the vertical slabs likely allowed the soul of the deceased to reach rial chamber so it could be reunited with the body.

Dolmen of Chianca

Between the 5th and the 3rd millennium BCE, megalithic cultures spread mainly in Atlantic Europe (Brittany, England, Ireland, northern Spain) but also in the Mediterranean area (southern France, Italy). They are named after the megaliths (from the Greek mégas 'great' and líthos 'stone'), large stones used to erect monumental works. They represent the first sign of a new will of Western man to create structures meant to last through time.

Dolmen of Chianca, the dromos.

The most common megalithic forms are:

• Dolmen (a word originating from the Celtic Tolmen – dol='table', men='stone' – which translates as 'Stone Table'): a type of burial chamber consisting of two large vertical stones supporting a flat horizontal capstone, and rarely preceded by an entrance corridor (dromos) bordered by two rows of slabs driven into the ground. This trilithon is the first example of an architectural structure consisting of an architrave (the capstone) supported by load-bearing elements (the two vertical stones).

• Menhir (from Breton men='stone', hir='long'): gigantic, parallelepiped-shaped monoliths up to 20 meters high, stuck upright into the ground. It was believed they cured infertility because their broad faces are oriented east and west and are always illuminated by the sun from dawn to dusk; they had a ritual function linked to the cult of the sun or the fertility of the Earth Mother goddess widespread in the Neolithic. However, it is more likely that they marked the burial place of a leader or an important shaman. In Roman times, they were used as road markers since they were often located near crossroads.

• Cromlech (from Welsh Crom='curved' and lech='flat stone'): multiple menhirs arranged in a circle.

We know that megalithic populations were not entirely stable but, after long periods, would move en masse toward other locations. Before migrating, they covered the tombs with mounds of earth and stones (specchie) to prevent the tombs from being harassed and the bodies of their loved ones from being violated.

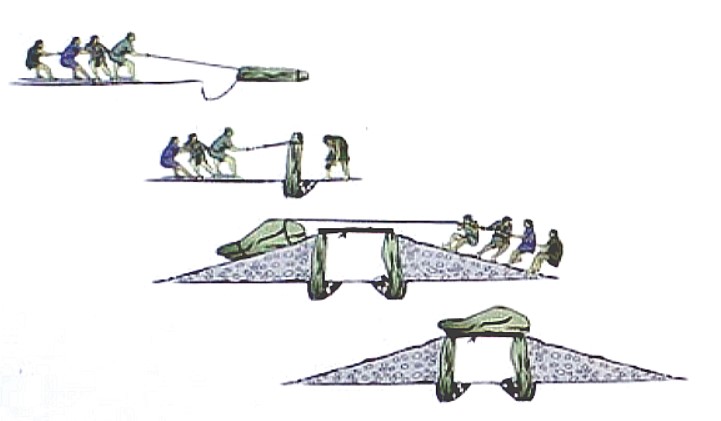

In ancient times, these prehistoric monuments were defined as works of giants. They served as landmarks and meeting points for communities, sometimes coming from distant lands, on special occasions. Their construction could require the coordinated effort of a hundred or more people.

Construction of a dolmen

Megalithic architecture is documented in Apulia by numerous dolmens and menhirs scattered throughout the territory. Popular imagination called them Houses of Giants (or of fairies or devils), while in France they were often considered shelters for legendary characters such as Roland and Gargantua.

In 380 CE, the emperors Gratian, Theodosius I, and Valentinian II promulgated the Edict of Thessalonica. This document proclaimed Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire. This was an implicit condemnation of pagan worship, which risked leading to the demolition of megalithic works. Fortunately, the people of Apulia found a compromise: the structures would be spared provided that iron crosses were placed on top of some menhirs, while on others, crosses were engraved to exorcise any residual pagan energy. Their name was also changed to "Hosanna."

Even today, rites that exorcise devils and witches are performed during Palm Sunday in some villages and towns of Lower Salento. For example, some farmers beat bundles of blessed palms and olive branches against menhirs, and processions end near menhirs used as hosannas.

During the Middle Ages, megalithic monuments continued to be objects of worship. The Church tried to repress pagan rites through a series of councils. But it was only after an edict by Charlemagne that many were destroyed. From 800 to today, it is estimated that 65 menhirs have been demolished.

Engraved crosses on a menhir

The Chianca dolmen, nestled in the countryside and surrounded by olive trees, was famous even in Roman times. It is considered one of the most important in Europe and is also very well preserved. In 2011, it was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It dates back to the Bronze Age and belongs to the type of tomb with a wide corridor, composed of a burial chamber and an access corridor (dromos).

"Chianca" derives from an Apulian dialect expression (chienghe) which means 'table,' exactly like dol from the Celts of Lower Brittany or planca from Latin. It undoubtedly refers to the main part of the monument: the large slab forming the roof.

The dolmen has a total length of just under 10 meters and is formed by four large stone blocks that constitute the burial chamber and other smaller ones that form a corridor (7.80 meters), which was perhaps once covered.

Via Stradelle, 76011 Bisceglie (Barletta-Andria-Trani)