Barumini in the heart of Sardinia

Cagliari, Italy

For the peoples of the Mediterranean, the need to address the lack of local resources acted as a major incentive for the development of trade networks throughout the basin. During the Paleolithic and Neolithic eras, they did not face significant difficulties in finding raw materials like flint or obsidian needed for toolmaking. However, securing metals like tin and iron became a greater challenge in the subsequent Metal Ages. In fact, tin had to be imported at high cost since the Bronze Age (an alloy of copper and tin), as it was mined only in distant locations like Cornwall and, in smaller quantities, Asturias and Andalusia. Consequently, between the third and first millennia BCE, a period defined by bronze and iron working, Neolithic societies transformed into cultures primarily focused on trade.

Sardinia, the second-largest island in the Mediterranean, occupied a strategic position in the basin and was rich in metal deposits. The Nuragic civilization (named for its characteristic structures, the nuraghi) began to develop on the island in the second millennium BCE. It was one of the most original and advanced cultures of its time in the Italian territory: composed of several small, pastoral communities (likely more shepherds than farmers), it was very belligerent and perhaps did not develop a writing system. Over the centuries, it came under the influence of Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans. Phoenician colonization pushed the Nuragic people into the island's interior but also integrated them into Mediterranean trade circuits from the 7th century BCE onwards. In fact, the civilization reached its peak development between 1000 and 500 BCE, which ended around 241 BCE when Sardinia became Roman. However, full Romanization succeeded only centuries later, during the Augustan and Julio-Claudian period (27 BCE – 68 CE), as evidenced by the late spread of typically Roman structures like villas and baths.

Inside Su Nuraxi at Barùmini (by Nicola Castangia)

The word nuraghe probably derives from the root nur, an ancient indigenous word meaning 'cluster of stones,' which aligns with the Babylonian word nuhàr, meaning 'tower' or 'temple.' A nuraghe is a truncated-conical megalithic building with a single entrance. Shaped like a defensive tower, it was constructed with large dry-laid boulders. It served as a dwelling, warehouse, lookout post over agricultural fields and domesticated animals, and, most importantly, as a fortress for shelter during raids from neighboring tribes. Sometimes, it could be part of a larger complex for religious worship or social gatherings. The nuraghi are the largest megalithic buildings in Europe. Their distribution is limited almost exclusively to Sardinia, beginning at the end of the ancient Bronze Age. Dating from the second millennium BCE, approximately 7,000 were erected (with many still buried or unknown), primarily between 1800 and 500 BCE.

Su Nuraxi at Barùmini (Cagliari)

The nuraghi were surrounded by stone walls and often grouped together, forming fortified housing complexes; for this reason, each nuraghe was typically in visual contact with at least two others. The most significant example of this architecture is undoubtedly the archaeological area of Su Nuraxi at Barumini. Located on the western outskirts of Barumini, about sixty kilometers from Cagliari, it consists of an imposing complex nuraghe (featuring more than one tower) with the appearance of a medieval castle but predating it by almost 3,000 years. It was built on a hill 238 meters above sea level during the second millennium BCE. A village was built around its walls in the middle of the first millennium BCE and housed up to 1,000 inhabitants.

Ideal reconstruction of Su Nuraxi at Barùmini, 1000 BCE (sardegnacultura.it)

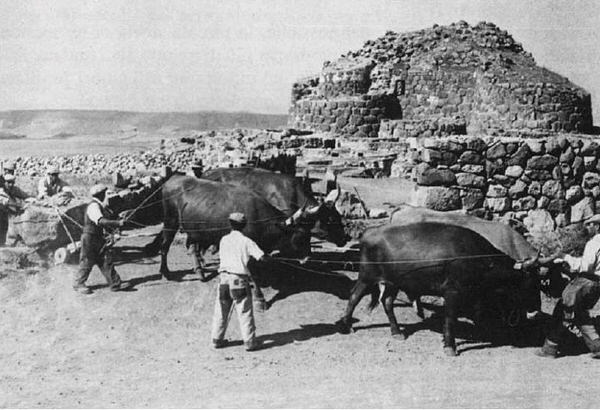

The first people to notice the presence of archaeological structures on the artificial hill of "Bruncu Su Nuraxi" were the farm laborers who worked this land, in the immediate post-war period. They would plow over it and sow barley and fava beans. Wheat was not an option, as the soil was too shallow and unsuitable for it. What the people of Barumini called Sa Funtana (the fountain) was, in fact, one of the bastion's towers. In the 1950s, a systematic archaeological excavation campaign was launched to unearth the nuraghe structure, which collapses over time had almost completely covered with earth and grassy vegetation. Over five years, around forty farm laborers—mostly war veterans—a hundred workers from Barumini, and several oxen, led by archaeologist Giovanni Lilliu, succeeded in bringing Su Nuraxi di Barumini back to light after millennia.

The archaeological area of Su Nuraxi in 1954

The complex of Su Nuraxi (from the Sardinian for 'the nuraghe') at Barumini is one of the largest Nuragic villages in Sardinia. Numerous modifications were layered onto its original structure, making it a site of great interest today. It was included by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site in 1997.

The nuraghe and village were strategically connected to a system of dozens of other nuraghi and Nuragic sites, such as the one found beneath Casa Zapata, less than a kilometer away.

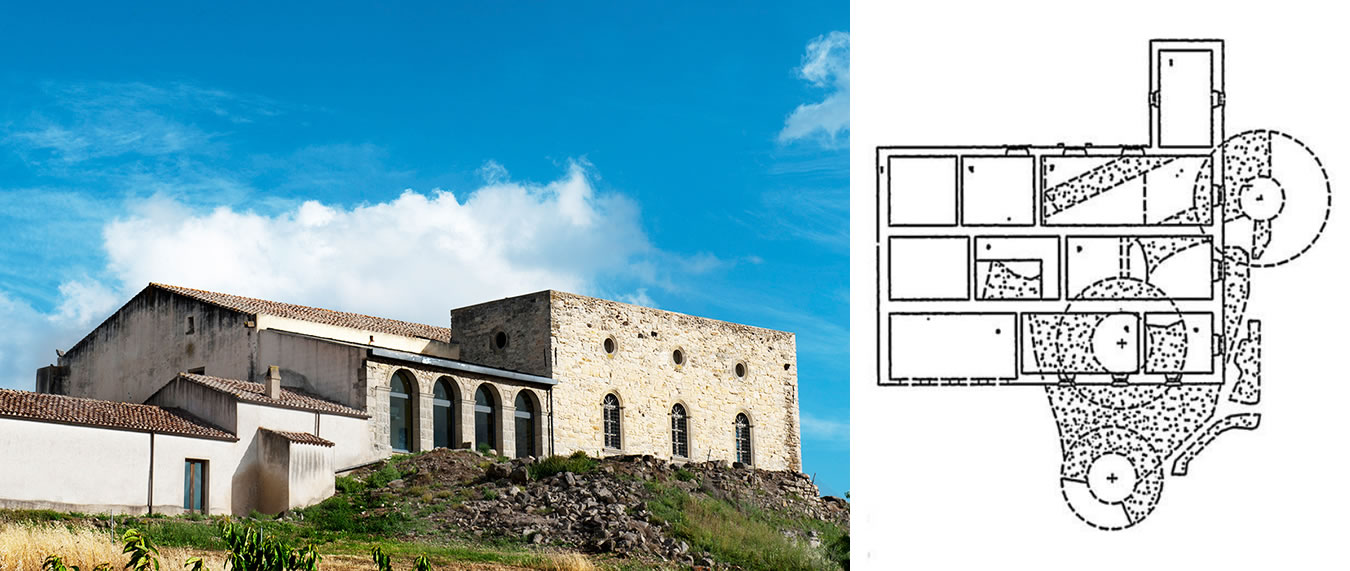

Zapata'a House

Casa Zapata (or su Palazzu ‘e su marchesu, the Marquis's palace) is a jewel of Sardinian architecture. It was erected at the end of the 16th century by the ancient and noble Aragonese Zapata family (Çapata or Sapata), who were present in Sardinia from 1323 to 1946. In 1990, after the death of the last Baroness, Donna Concetta Ingarao Zapata, the town of Barumini purchased the abandoned Zapata House to convert it into a museum. During renovation works, workers discovered the remains of a Nuragic settlement beneath the floors. They first found a nuraghe nicknamed "of the church" (su Nuraxi ‘e Cresia) and later other archaeological remains near the parish church (su Nuraxi sa Cresia manna, large church). Excavations are still ongoing. The museum is open to visitors, and through a system of suspended walkways and glass floors, one can admire the Nuragic complex from above.

Plan of the archaeological remains of the nuraghe Su Nuraxi ’e Cresia

Barumini was a fief of the Zapata family until 1840. The presence of ancient, largely ruined buildings was known even then, but they had never been properly identified. Some remains of the buried nuraghi of Su Nuraxi began to be studied and unearthed a century later. The excavations have allowed scholars to trace the different construction phases, confirming the entire complex was inhabited until the first century BCE, in Roman times, even though the nuraghe was already a ruin and was used by the Romans as a burial ground.

Viale Su Nuraxi, Barumini;

Casa Zapata: Piazza Papa Giovanni XXIII, Barumini.