The freedom enjoyed by Etruscan women at Banditaccia (Caere)

Rome, Italy

The Etruscans were an ancient Mediterranean civilization that thrived from the 9th to the 1st century BCE. To the Greek poet Homer (8th century BCE), they were monstrously fierce pirates who jealously guarded access to the sea that still bears their name.

The Greek historian and geographer Herodotus (484-425 BCE) provided an account of Etruscan origins that was almost universally accepted in antiquity, except by Dionysius of Halicarnassus (c. 60-7 BCE). According to this story, they were inhabitants of Lydia in Asia Minor who decided to emigrate. They followed one of the sons of their king to the country of the Ombrikoi. By Ombrikoi, Herodotus, like all Greek writers, meant the Umbrians, who according to tradition once occupied a much larger part of Italy than the modern province of that name. The Lydians settled among them and called themselves Tyrsenoi after the name of the prince who led them.

During the 6th to 5th centuries BCE, the word Tyrrhenian referred specifically to the Etruscans, for whom the Tyrrhenian Sea is named, as noted by the Greek geographer, philosopher, and historian Strabo (c. 64 BCE - 24 CE).

The Roman historian Livy (59 BCE - 17 CE) wrote: "the renown of their name filled the whole length of Italy from the Alps to the Sicilian strait."

What we know for certain is that their cities appear to have developed from the preceding terramare culture, and initially, they lived in ancient central Italy (Tuscany, western Umbria, and northern Lazio). After conquering adjacent lands, their territory (Etruria) covered a significant part of the northern and southern peninsula.

They shared a common language and culture and formed an early federation of 12 city-states (the Dodecapolis, Greek for twelve cities). The Romans derived a great deal of cultural influence from them. The growth of their city-states is related to the acquisition of wealth through trade.

Etruscan territories, city-states and major spread pathways of Etruscan products

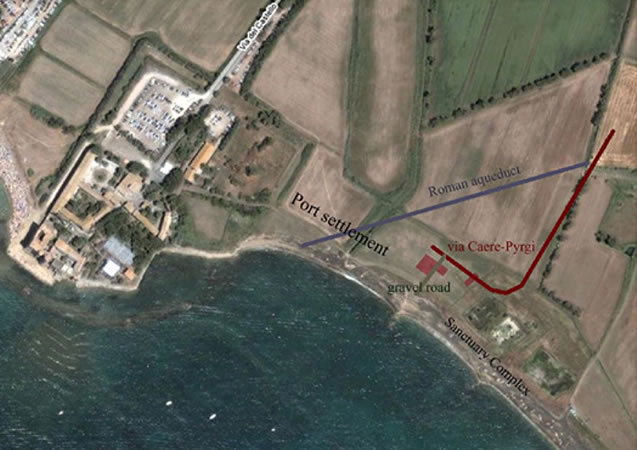

The wealthier Etruscan cities were located a safe distance, about 5 km from the sea coast. An example was Caisra or Cisra (known as Caere or Agylla to the Romans), the modern town of Cerveteri (approximately 50–60 kilometres north-northwest of Rome). It was one of the most important and populous cities of the Etruscan League and one of the larger ones in southern Etruria; in fact, ancient Caere occupied an area 15 times larger than modern Cerveteri. Caisra had three seaports, which were crucial for overseas trade. Pyrgi was the natural port and hosted sanctuaries for foreign worship.

Pyrgi, the seaport and the sanctuaries

Today, the area of Cerveteri and Banditaccia is best known for its Etruscan necropolis (cemetery) and archaeological treasures. Banditaccia is the site of the largest necropolis of Caisra and is also one of the largest in the ancient Mediterranean world. It includes thousands of graves arranged like a city with neighborhoods and streets. It extends for about 400 hectares, though only a fenced-off portion of 10 hectares is visitable and contains about 400 burial mounds. It developed from the 9th century BCE (the Villanovan period) until the 3rd century BCE (the Hellenistic-Roman period) and is traversed by a burial road more than 2 km long. The hundreds of circular mounds belonged to high-ranking families and have yielded rich grave goods, including objects imported from the Near East and Greece.

Etruscan road dug in the tuff at Banditaccia Necropolis, note the grooves created by the wheels of the ancient carts

The tombs were dug into the tuff rock, inside a round mound. Their interiors resembled Etruscan houses, complete with beds, chairs, and reproductions of objects the deceased used daily.

Observing the tombs, it is easy to understand how the family (lautn) was the center of Etruscan society, while the married couple (tusurthir) was the center of the family. The Etruscans were a monogamous society that emphasized pairing:

• The lids of large numbers of sarcophagi were decorated with images of smiling couples in the prime of their life, often reclining next to each other or in an embrace.

• Many tombs included funerary inscriptions naming the parents of the deceased—the father's name often written in Latin, and the mother's in Etruscan—because the mother's family origin was important in Etruscan society.

Tomb of the Reliefs, late 4th or early 3rd century BCE, Necropolis of Banditaccia (Cerveteri)

But observing the archaeological findings, we discover that the Etruscan woman was freer than her contemporaries in other cultures:

• Spindle whorls and spring scales show that she practiced manual work like spinning and weaving, while loom weights indicate she produced the luxurious robes and other goods for which Etruria was famous throughout the Mediterranean.

• Inscriptions on some of her mirrors, used to explain the scenes represented, show she could write and read.

• Funeral objects like exquisite Corinthian vases or glass vessels show that she used scented oils.

• Frescoes show she was perfectly attired and groomed: she applied cosmetics with ivory sticks and combed her hair with ivory combs; she flaunted large earrings; her finely woven dresses crinkled; she wore soft red shoes with flashy pointed toes; her pale skin was set off by flushed cheeks and deep red lips. She participated in public life or events (as a spectator or participant), banquets, and rode in carriages.

Sharing wives is an established Etruscan custom. Etruscan women take particular care of their bodies and exercise sometimes along with the men, and sometimes by themselves. It is not a disgrace for them to be seen naked. They do not share their couches with their husbands but with the other men who happen to be present, and they propose toasts to anyone they choose. They are expert drinkers and very attractive.

The Etruscans raise all the children that are born, without knowing who their fathers are. The children live the way their parents live, often attending drinking parties and having sexual relations with all the women. It is no disgrace for them to do anything in the open, or to be seen having it done to them, for they consider it a native custom.

Theopompus’s account, which goes on to discuss public displays of affection, spouse-swapping, and other licentious behavior, is almost certainly exaggerated. The men and women who recline together in famous sarcophagi from Banditaccia seem overwhelmingly to be married couples. Their conviviality does not meet Roman standards of probity—a Roman general was never supposed to laugh—but the banquet scenes from the tombs show nothing like the wild parties held by the Greeks.

On April 9, 1881, came to light in countless fragments, the Sarcophagus of the Spouses (or Sarcophagus with Reclining Couple) at the Banditaccia necropolis, eastbound, Cerveteri, Italy, c. 530-520 BCE, painted terracotta, 3 feet 9 1/2 inches x 6 feet 7 inches (at the National Etruscan Museum in Rome's Villa Giulia). Reassembled from about four hundred fragments, the Sarcophagus of the spouses is actually an urn intended to accommodate the material remains of the deceased.

Etruscan women enjoyed a degree of freedom unheard of in the Greek and Roman worlds: they sang, they danced, they dined with men, and they were considered sexually loose. A sense of joyous freedom shines through two beautiful terracotta sarcophagi found at Banditaccia towards the end of the nineteenth century: one is now in the Museum of Villa Giulia in Rome, and the other in the Louvre Museum in Paris. A sarcophagus is a box-like funeral receptacle for a corpse, most commonly carved in stone and displayed above ground.

The Sarcophagi of the Spouses from Banditaccia (Caere) are considered masterpieces of Etruscan art. They are quite similar and contemporary, suggesting they are products of the same artistic workshop. They belong to practically the same generation as the marvellous Apollo of Veii.

Images of banquets begin as early as the sixth century BCE—the probable date of the Banditaccia sarcophagi. They show husband and wife reclining as equals as they participate in a banquet, probably a funerary banquet for the dead. This was an unimaginable attitude in contemporary Greece, where courtesans (hetairai), who were prostitutes, were the only women attending public banquets, or symposia, dancing and playing music. Roman women led similarly restricted lives, expected to be sober and silent in the presence of men. The affectionate gestures and tenderness between the Etruscan man and woman convey a strikingly different attitude about the status of women and their relative equality with their husbands.

We can note the freedoms enjoyed by Etruscan women in life (they dined alongside men, partaking of wine without reservation) and in death, too (their burials rivaling those of their male relatives, filled with great quantities of luxurious goods).

Sarcophagus of the Spouses, c. 520 BCE, Louvre Museum, Room 18.

The body of the sarcophagus is styled to resemble a kline (the convivial bed on which banquet guests reclined). The figures are half-sitting, half-reclining, resting on highly stylized cushions, and are finely finished (for example, they have hair plaited in stylized braids hanging rather stiffly at the sides of the neck). The husband is a grave and dignified personage, wearing long hair and a well-shaped beard but with a clean-shaven upper lip. The wife has long plaited tresses hanging down her shoulders; she wears a soft cap atop her head—as every lady of rank did—and shoes with characteristically Etruscan pointed toes. She is not wearing the jewellery and heavy ornaments she would have worn in life, but which have been discovered in the tombs.

What we do not know is what the figures were holding in their curled fingers. The arm positions of both figures hint that each must have held small objects. Since the wife and husband are reclining on a banqueting couch, the objects could have been vessels associated with drinking, perhaps wine cups, or representations of food. Another possibility is that they may have held small vessels containing oil used for anointing the dead. Or, perhaps, they held all of the above—food, drink, and oil, each a necessity for the journey from this life to the next.

A pair of terracotta cinerary urns, always coming from the necropolis of Banditaccia, Cerveteri - 5th century BCE. Note how the similarity of the urns (size and decorations) testifies to the equality between wife and husband.

Whatever the missing elements, the conviviality of the moment and the intimacy of the figures capture the life-affirming quality often seen in Etruscan art of this period, even in the face of death.

But the spouses were not always represented side by side. A pair of terracotta cinerary urns—also from the Banditaccia necropolis and dating to the 5th century BCE—containing the remains of two spouses, depicts them respectively on their own kline (Tharnas). The lower part of the urns is identical, featuring a bas-relief on the side of the beds where two felines are represented attacking their prey, and two naked, semi-reclining male figures. Note how the similarity of the urns (size and decorations) also testifies to the equality between wife and husband.

A view of Banditaccia Necropolis, Cerveteri - 1970

The Veientes, therefore, having suffered greatly from that battle, stirred no more out of their city but suffered their country to be laid waste before their eyes. King Tarquinius made three incursions into their territory and for a period of three years deprived them of the produce of their land; but when he had laid waste the greater part of their country and was unable to do any further damage to it, he led his army against the city of the Caeretani, which earlier had been called Agylla while it was inhabited by the Pelasgians but after falling under the power of the Tyrrhenians had been renamed Caere, and was as flourishing and populous as any city in Tyrrhenia.

- DIONYSIUS OF HALICARNASSUS, ROMAN ANTIQUITIES § 3.58.1, Event Date: -525 GR

A view of Banditaccia necropolis, Cerveteri (Caere)

Via della Necropoli, Cerveteri (Rome)