The Last Giant: Alexander Severus' Aqueduct and Its 22 Kilometers of Eternity

Rome, Italy

Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander (208-235 AD) was born in Arca Caesarea, an ancient city in Syria that had become a Roman colony. His original name, it seems, was Alexianus. We know very little about his father, Gessius Marcianus, but his mother, Julia Avita Mamaea – daughter of Julia Maesa and sister of Julia Soaemias – is known to have been an overbearing and domineering figure. Alexianus received his early education alongside his cousin Elagabalus under their grandmother Maesa, who was living in exile in Emesa, and was consecrated, like Elagabalus, to the cult of the Sun God. When Elagabalus, proclaimed emperor, moved to Rome (218), Mamaea and Alexianus followed him. However, Alexianus was kept away from the court's scandals by his mother, which allowed him to win the favour of those soldiers disgusted by Elagabalus's lifestyle. Matters reached the point where Elagabalus was forced to adopt Alexianus and name him Caesar; the adopted son took the name Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander (221). Soon, however, Elagabalus found himself compelled to make further concessions, investing him with the title of Emperor and Augustus, while simultaneously plotting to eliminate him. Before he could succeed, Elagabalus was removed in a military uprising orchestrated by Mamaea (222).

Thus, Alexander became sole emperor. He was only thirteen and a half years old; consequently, the governance of the empire remained firmly in the hands of the elderly Maesa, soon joined by Mamaea, who was left alone after Maesa died shortly thereafter. To secure the army's favour, Mamaea spread the rumour that Alexander was the son of Caracalla; however, the effects of this ploy, which gave Alexander a third paternity, do not seem to have been very significant.

The women at court held immense power, continuing the trend seen under Elagabalus; the Syrian family had taken the reins of government, yet failed to grasp that power in Rome was founded on the army, and that its support was indispensable. Indeed, the regimes of Caracalla and Elagabalus had left the legions deeply resentful. Sedition erupted in various places. The streets of Rome were the scene of clashes between the Praetorian Guard and citizens for three days, with the latter naturally suffering the worst. The soldiers' anger was now directed against Mamaea, accused of greed and held responsible for the army's grievances.

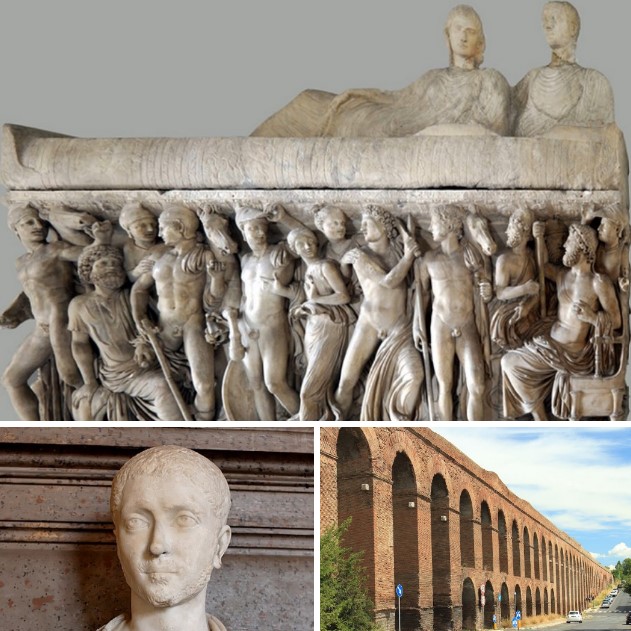

In any case, Alexander too would be eliminated, like many of his predecessors and successors. In 235, he and his mother were killed in a revolt by his own legions – in this instance, the western legions. The ashes of Alexander and his mother were entombed in a sarcophagus decorated with scenes from the myth of Achilles. It is now housed in the Capitoline Museums but was originally placed in a grand mausoleum, today known as Monte del Grano in Rome.

A section of the Alexandrian Aqueduct; a bust of the eponymous emperor; and his marble sarcophagus (3rd century AD) from the "Monte del Grano" – between Via Tuscolana and Via Labicana – now kept in the Capitoline Museums, Rome.

Alexander was noble and mild-mannered. He had a good Hellenic education, displayed an admirable appreciation for the arts, but knew little Latin and consequently spoke it rarely and reluctantly. At heart, he remained an Easterner.

Remembered in history as an example of a good emperor, he respected the Senate's prerogatives and cared for his subjects. He did not increase the tax burden and promoted religious syncretism.

He also focused on Rome: improving its roads, and commissioning new baths and a new aqueduct to supply them.

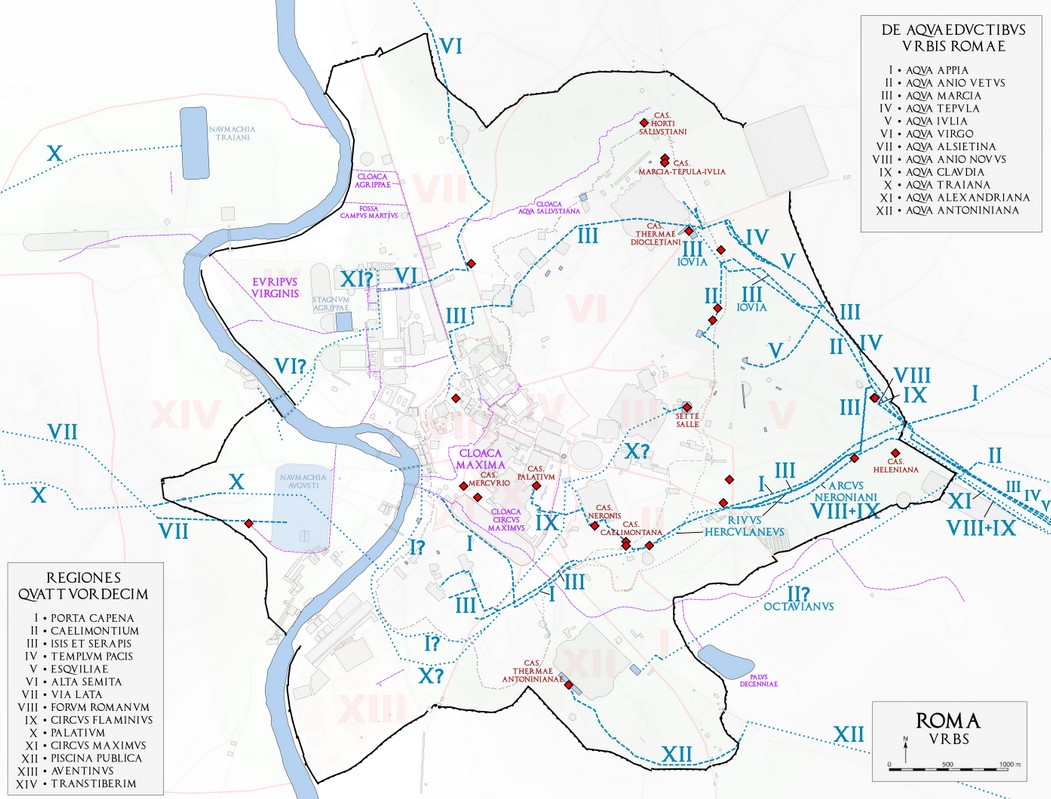

Map of ancient Rome showing the water distribution system via the aqueducts and castella and the sewage system from the foundation of the city until the fourth century AD. Map based after Rodolfo Lanciani, Forma Urbis, completed and corrected with the most recent archaeological proposals and discoveries.

The springs of the Aqua Alexandrina (Alexandrian Aqueduct) were located three kilometres north of the territory of Colonna (Pantano Borghese, opposite Gabii, about 20 km east of Rome). They were later used by Pope Sixtus V for the construction of his Acqua Felice aqueduct.

With a mixed route – underground and via viaducts to cross valleys – the imposing aqueduct entered Rome in 226 AD ad spem veterem, near Porta Maggiore, and headed towards the Campus Martius. Here, Alexander Severus himself had restored the Baths of Nero, henceforth known as the Thermae Alexandrinae, which were thus provided with an autonomous water supply.

The aqueduct, stretching approximately 22 km, was an extraordinary testament to Roman hydraulic engineering. It was the third largest in daily capacity at 21,632 m³ and was the last of the great Roman aqueducts. After over 1800 years of history, it still stands proudly with magnificent arches visible at various points along its course.

The characteristic brick curtain walls underwent numerous interventions over the centuries. In the 3rd-4th century AD, they were refaced with brick, restoring the original appearance of the structure. During this same period, piers were added to the original arches to strengthen them. In the 5th-6th century AD, the entire aqueduct structure was refaced in opera listata (small tufa blocks alternating with brick courses), and collapsed arches were rebuilt.

Significant work was undertaken by Pope Adrian I (772-795), who reinforced the structure using repurposed squared stone blocks. He repaired the curtain walls, again using spolia (small tufa blocks and bricks laid with undulating beds), and built watchtowers. Exploiting the height of the ancient structure, these towers commanded wide views, particularly controlling the intermediate road network.

Later, as we know, the Alexandrian Aqueduct was repurposed and restored by Pope Sixtus V in 1585. He rebuilt much of the original course to supply his vast estate and gardens at Villa Montalto (now the site of the National Roman Museum near Termini Station) and eventually also fed the beautiful Fontana del Mosè. Pope Sixtus V, born Felice Peretti di Montalto, named the restored aqueduct the Acqua Felice. For Romans, it became the Acquedotto Felice. Its arches are clearly visible, notably the fine arch in Via Marsala and the famous Porta Furba in the Tuscolano area.

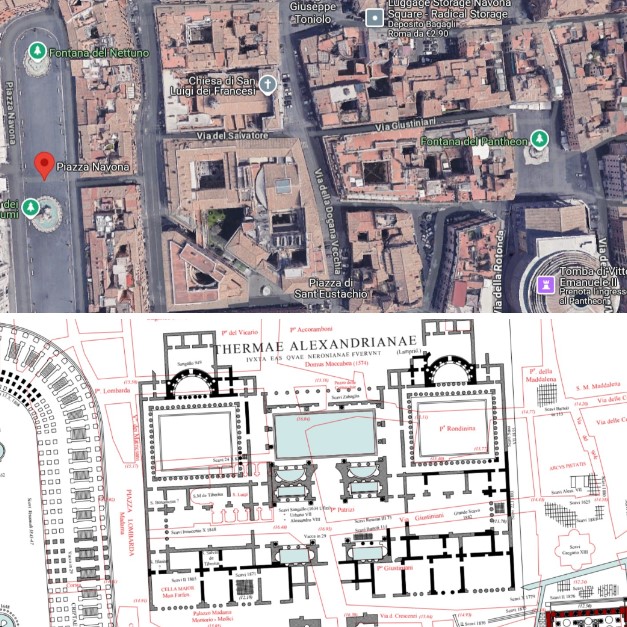

Location of the Baths of Nero / Alexandrian Baths

In 62 AD, Emperor Nero commissioned grandiose baths. Unlike Agrippa's baths built about a century earlier, however, these were reserved solely for him and his court. They were located in the area bounded by present-day Piazza della Rotonda, Via del Pozzo delle Cornacchie, and Via della Dogana Vecchia, covering an area of 30,000 m². They differed structurally from Agrippa's baths by following the typical imperial axial and symmetrical layout, with its rooms aligned according to the cardinal points. They were the first baths built according to this scheme. They were supplied by the Aqua Virgo, the same aqueduct feeding Agrippa's Baths; Nero had a branch constructed from it.

In 64 AD, the Great Fire devastated much of the city, for which Christians were blamed. Nero's baths, however, were not affected. This is deduced from a passage in Tacitus's Annals, stating that the emperor offered the Gardens of Agrippa, his baths, and the nearby Pantheon to assist citizens who had lost their homes in the fire.

The baths were then renovated in 227 AD by Alexander Severus. From then on, they were called the Thermae Alexandrinae: they became public and were supplied by the Aqua Alexandrina, specially built by him. The emperor made modifications to the complex, possibly enlarging it and changing the construction technique to the typical brickwork (opus latericium) of his period. The central feature of the baths was the Natatio (large swimming pool), around which other rooms were arranged: the Caldarium (hot room), Tepidarium (warm room), and Palaestra (exercise yard). They were undoubtedly magnificent, like the Neronian Baths before them. Indeed, the poet Martial wrote in his Epigrams:

What was worse than Nero? What was better than Nero’s Baths?

According to Sidonius Apollinaris, they were still in use in the 5th century AD. Over time, they were stripped of their precious decorations. These were reused in noble palaces, churches (including St. Peter's Basilica), the Pantheon (two pink granite columns reused in the 1666 restoration of the pronaos), placed in squares (a cornice and two columns are currently re-erected near the bath remains in Piazza Sant'Eustachio, while another column was re-erected in 1896 near Porta Pia), or in gardens (a monumental basin, once in the Villa Medici collections, is now in the amphitheatre of the Boboli Gardens in Florence, while a monumental capital, currently in the Vatican Museums' Cortile della Pigna, serves as the base for the Pinecone).

Some decorative elements from the Alexandrian Baths: fountain in Piazza della Costituente; two columns in the Pantheon; two columns in Via di S. Eustachio, Rome; the monumental capital supporting the Pinecone in the Cortile della Pigna of the Vatican Museums; and a monumental basin in the Boboli Gardens, Florence.

Remains of the baths lie beneath the Palazzo del Senato and the Palazzo Giustiniani. Inside the latter, numerous artifacts can be found; indeed, when the palace was built, it was enriched and decorated with many statues and reliefs from the baths. The Church of San Luigi dei Francesi itself stands above one of the ancient bath halls, and its floor preserves parts of the original Roman marble pavement. Furthermore, during archaeological excavations beneath Palazzo Madama in the 1980s, a large basin made of polychrome Egyptian granite was discovered. It was certainly used in the caldarium of the baths. The then President of the Senate, Giovanni Spadolini, donated the artifact to the city of Rome. It was placed as a fountain on a Renaissance pedestal in the small square, subsequently renamed 'Piazza della Costituente', connecting Via degli Staderari with Via della Dogana Vecchia and Piazza Sant'Eustachio.

Rome, Via di S. Eustachio, 20