The Acemetes: Rome’s Sleepless Monks

Rome, Italy

Monti (R.I.) is Rome’s first rione (district). Those strolling its streets today often overlook that these lanes tell a 2,000-year-old tale, dating back to when Rome was still shaping its urban identity.

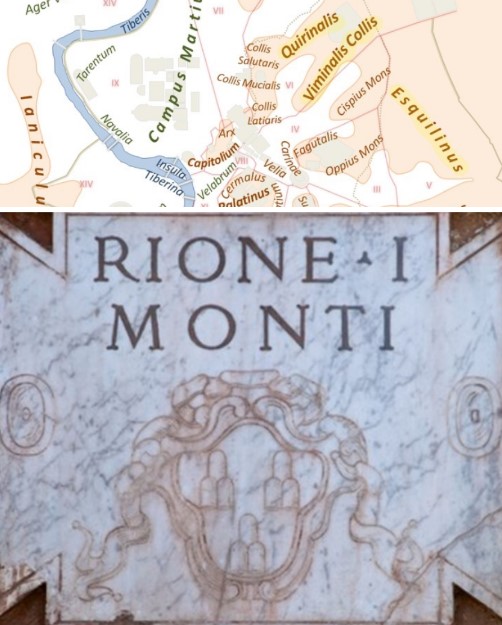

Its name originates from the Middle Ages term "li monti" (the hills), referring to the sparsely populated area encompassing three of Rome’s seven hills: Esquiline, Viminal, and part of the Quirinal. Today, the Esquiline—once featured on Monti’s coat of arms—no longer belongs to the district.

Coat of Arms of Rione Monti and a schematic map of Rome showing the seven hills and the Servian Wall

In ancient Rome, this area was Julius Caesar’s birthplace. It was densely populated: the upper sector hosted aristocratic domus, while the low-lying (Suburra) —marshy until drained by the Cloaca Maxima—was a plebeian zone notorious for its brothels and disreputable taverns. Farther down, in the valley between the Capitoline and Palatine hills, stood the Imperial Forums. Separated from the fire-prone working-class district by a massive firebreak wall (still framing the Forum of Augustus today), the area faced constant peril.

Roman aqueducts were damaged by warfare, such as the 537 AD siege of Rome by Vitiges’ Goths, who severed them to cut off the city’s water supply. Centuries later, in the Middle Ages, Monti’s elevated terrain still hindered water access, driving residents toward the Tiber’s drinkable waters in lower plains.

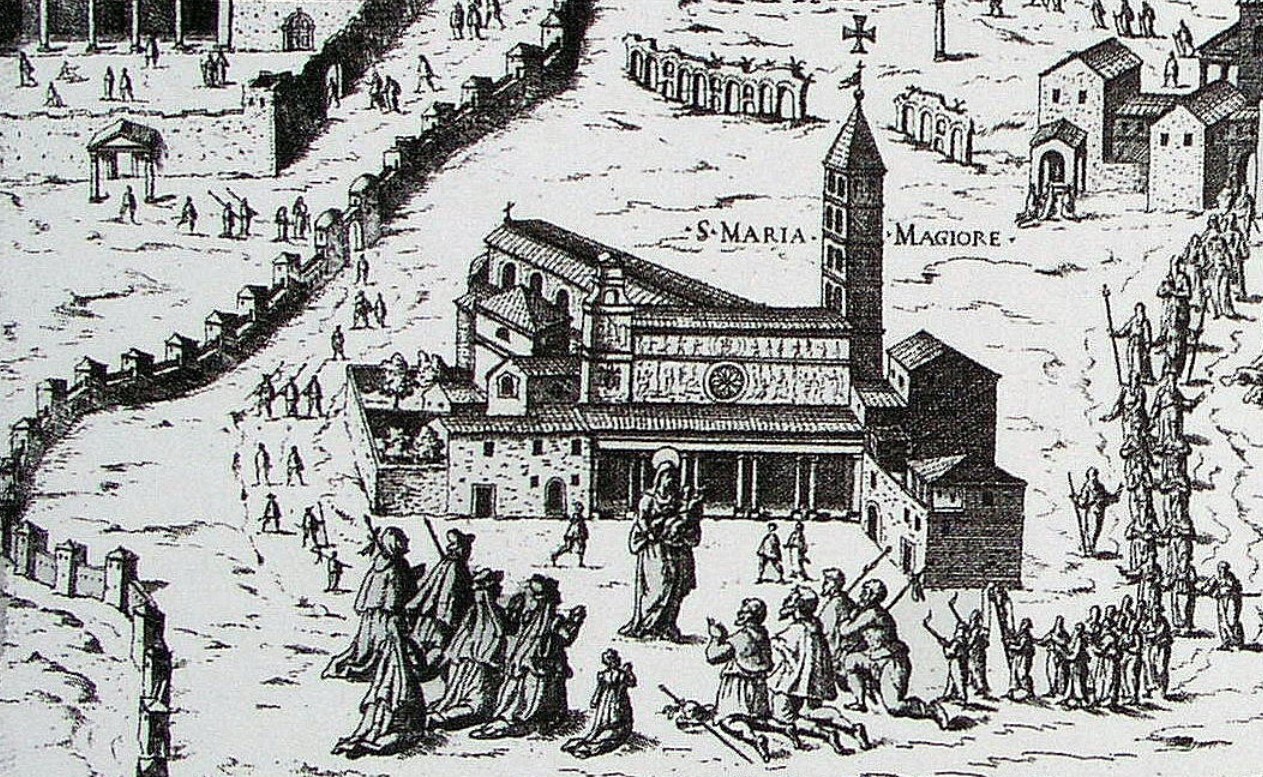

From the Middle Ages until the early 1800s, Monti remained a vineyard- and garden-rich area, sparsely populated due to water scarcity and distance from the cultural hub of St. Peter’s Basilica. Its survival as a habitable zone relied solely on the Basilicas of St. John Lateran and Saint Mary Major, whose steady stream of pilgrims ensured a constant presence.

Detail of Saint Mary Major. 'The Seven Churches of Rome', copper engraving from Speculum romanae magnificentiae, 1575 (Antoine Lafréry)

In 431, the dogma of Theotòkos (divine motherhood) was proclaimed at the Council of Ephesus. Pope Sixtus III (432–446) thus commissioned a church dedicated solely to the Virgin. Built on the Esquiline Hill—where the ancient cult of Juno Lucina (protector of childbirth) merged with Marian veneration—the magnificent Basilica of Saint Mary Major rose in 432 AD to honor Mary, Mother of God.

To further celebrate the Madonna, relics from Bethlehem’s grotto and remnants of Jesus’ cradle (7th century AD) were transferred here, earning the basilica the nickname Santa Vergine ad praesepe (Holy Virgin at the Crib). Indeed, it houses not only stunning 5th-century mosaics but also the first depiction of the Nativity: history’s earliest inanimate nativity scene.

From the 15th century onward, the basilica underwent numerous renovations, including replacing its lost Paleochristian ceiling with a wood-coffered one commissioned by Spanish Pope Alexander VI (1431–1503) of the Borgia family. He adorned it with gold from the first shipment to Spain from the newly discovered Americas—a gift from the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile to the Mother of God.

The nativity scene (presepe) of Saint Mary Major, commissioned in 1288 by Pope Nicholas IV from Tuscan sculptor Arnolfo di Cambio (pupil of Nicola Pisano).

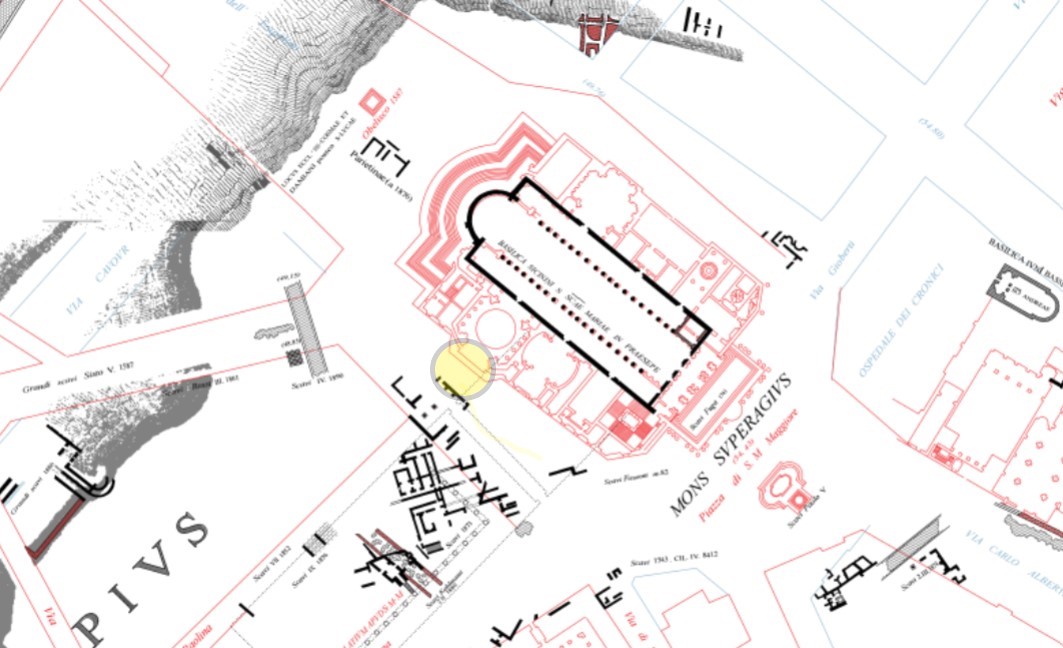

It was during this century that the church of the Acemete monks vanished. Pope Nicholas V (1447–1455) ordered the construction of the basilica’s Patriarchio (papal residence) on the site. This palace was altered so frequently—shifting between patriarchal seat, canonry, and papal residence—that it became unrecognizable. By the 19th century, its existence was even doubted.

Location of St. Hadrian ad Sanctae Mariae Maioris in the map of Rodolfo Lanciani

The small church and adjoining monastery (now lost) stood on today’s Via Liberiana. Dedicated to St. Adrian, a martyr of Nicomedia persecuted under Diocletian, it was known as "Sant’Adriano ad Sanctae Mariae Maioris." By the late 8th century AD, it lay abandoned and in ruins (in ruinis marcescebat a priscis temporibus), inhabited by the poor and beggars.

'Charlemagne and the Pope' by Antoine Vérard (1493). The Frankish king, a devout Catholic, aided Pope Adrian I against invaders in 772 AD. Depicted here: the pope requesting Charlemagne’s help near Rome.

Pope Adrian I restored it, endowed it with assets, and entrusted it to the Acemete monks. Like those in neighboring monasteries, they were tasked with "Deo die noctuque canentes, solitas dicere laudes" (singing God’s praises day and night without ceasing).

By the 14th century, Romans called it "Sant’Adrianello" — likely to distinguish it from the larger, more important Sant’Adriano al Foro nearby. It was also referenced as Sant’Adriano ad duo furna, possibly due to ruins of two aqueduct arches (fornici).

Monastery of San Saba (1787), Victor-Jean Nicolle. The church and convent housed Acemete monks who settled here around the 8th century. San Saba was one of Rome’s most important medieval monasteries, built atop a Roman oratory dedicated to St. Silvia (Pope Gregory the Great’s mother), later inhabited by hermits

Rome’s major basilicas—like the Vatican and Lateran—were served by Acemete monks. Monasteries near each ensured divine psalmody continued uninterrupted, day and night.

The Acemetes (from Greek akoímetoi: "sleepless ones") were Byzantine Christian monks of a community founded by St. Alexander in the early 5th century AD. They rose to prominence in the Church’s early centuries, peaking in the 5th–6th centuries in the East, and later spreading to the West (especially France).

To maintain perpetual psalmody, they rotated in eight-hour shifts, chanting psalms continuously—morning prayer (orthrinón/morning lauds), lamp lighting (lychnikón/vespers), pre-sleep prayer (prothýpnion/compline), and midnight prayer (mesonýktion/matins). This practice later evolved in the West into the laus perennis (perpetual praise).

Acemetes wore distinctive green robes with a double red cross on the chest. Their exemplary lives produced numerous Eastern Church saints, bishops, and patriarchs.

Suspected of Nestorianism and opposed by Emperor Justinian, they were condemned by Pope John II in 534 AD and vanished by the late 6th century.

Via Liberiana (Rome)