Acca Larentia, a semi-divine prostitute and mother of the Lares

Rome, Italy

Acca Larentia is a figure from Roman mythology, regarded as a semi-divine character inherited from the Etruscans as a prostitute who protected the humble populace. She was born in Alba Longa, the village founded—according to legend—by Ascanius, son of Aeneas, around the mid-12th century BCE, shortly after the destruction of Troy (dated by ancient scholars to 1184 BCE).

Her name, Acca Larentia (Latin: Ăcca Lārentĭa or Laurentĭa,-ae) has two components: Acca derives from an Indo-European root meaning ‘mother,’ with cognates in Sanskrit (akka) and Greek (akkw), though it is uniquely attested in Latin. The second part is considered a derivative of Lar (despite uncertainty due to the vowel length difference), making Acca Larentia the Mater Larum(Mother of the Lares)—a highly significant yet obscure deity in the Roman pantheon, worshipped under various names (Lara, Larunda, Mania, Tacita, and possibly Genita Mana and Fauna).

Graphic Reconstruction: The Tiber River, the Cermalus with the Lupercal, and Faustulus’s hut with the Capitoline Hill in the background.

On December 23, the Accalia or Larentalia was celebrated. On this day, the flamen Quirinalis (priest of Quirinus) and the pontiffs offered funerary sacrifices and wine libations at the tomb of Acca Larentia (or Larentina, meaning ‘Mother of the Lares’). This was the final festival of the archaic calendar, closing the year.

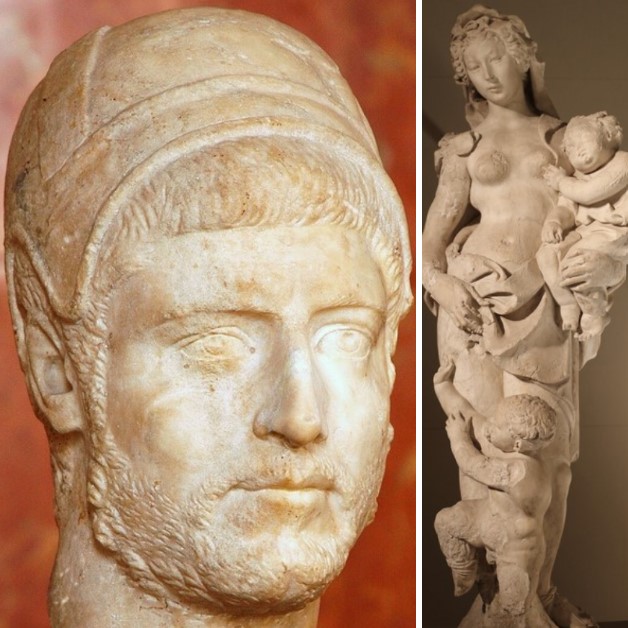

Siena, Santa Maria della Scala Hospital - Sculptures from Fonte Gaia by Jacopo della Quercia; and a portrait of a flamen quirinalis in Louvre Museum, Paris

Her tomb was located at the edge of the Velabrum—at the foot of the Aventine Hill, near the mouth of the Nova via [Var. L. L. VI, 23 – 24; Plut. Rom. IV; Cic. Ad Brut. I, 15, 8; Gel. VII, 7, 6; Macr. Sat. I, 10, 15]. This was a transitional zone between the Roman Forum and the Palatine, inhabited by Etruscans in the archaic era. Today, it is identifiable behind the Temple of Vesta, precisely where theShrine of Juturna stands. It was likely an archaic tomb, a remnant of the ancient necropolis that once occupied much of the Forum valley. The area’s connection to the earliest Palatine settlement (the porta Romanula, the fourth corner of Romulus’s pomerium recalled by Tacitus) and the calendrical position of the Larentalia point to a “liminal” cult—both spatially and temporally—dating to a pre-urban, pastoral society.

he ritual’s antiquity is confirmed by Varro’s use of the name Larental. . Another name for the festival was dies Tarentus, from an alternate name for the deity honored: Acca Tarentina [Varro, Lingua Latina VI, 24]. On the same day, the gens Junia honored their dead with a parentatio (ancestral rite) [Plutarch, Roman Questions 34].

Two main traditions, enriched by variants, exist about Acca Larentia:

The Ficus Ruminalis in the Roman Forum, before the Column of Phocas. The epithet ruminalis may derive from Romulus’s name, from ruminant animals sheltering under it, or—most plausibly—because the divine twins were suckled by the she-wolf (lupa) in its shade. Romans called breasts rumae and venerated a goddess Rumina, believed to oversee child-rearing (Plutarch, Romulus IV, 1). Alternatively, "Ruminal" may come from the nearby river, archaically called Rumon. Ancient historians recount that the tree miraculously moved from the Palatine to the Forum’s center, where it remained venerated throughout the Empire. In 58 CE, the ancient trunk—after 840 years (Pliny, Natural History XV, 77; Tacitus, Annals XIII, 58)—withered and leafless, miraculously regreened. Reconciling accounts of the Ficus Ruminalis near the Lupercal with those placing it in the Forum is highly uncertain; interpretations of the cult and the name’s etymology depend on resolving this. The Forum still shows the unpaved area where the fig, olive, and vine grew, alongside a statue of Marsyas with a wineskin, as depicted on Trajan’s nearby reliefs.

First Tradition: The twins Romulus and Remus, abandoned in a basket on the Tiber, were carried by the flood to a cave near the ficus ruminalis at the Palatine’s base toward the Velabrum [Livy I, 4, 6; Plutarch, Romulus IV; Lactantius, Divine Institutes I, 20; Dionysius of Halicarnassus I, 84, 2]. Nearby was the Lupercal grotto and spring.

In one variant, Faustulus’s wife—a descendant of Evander living near the Palatine—found the twins (or received them from Numitor). She was nicknamed lupa ("she-wolf," slang for prostitute) due to her wild nature and infidelity, often coupling with youths in the woods [Livy I, 4, 6–7; Dionysius I, 84, 2–4; Servius, Aeneid I, 273; Plutarch, Romulus IV; Roman Questions 35; Lactantius I, 20; Aulus Gellius VII, 7, 5–8; Festus 119; Tertullian, Ad Nationes II, 10; Ovid, Fasti III, 55ff; Augustine, City of God XVIII, 21].

Another variant states the twins were suckled by a she-wolf (lupa) and found by Faustulus, who brought them to his wife Acca Larentia.

The twins were sons of the Alban princess Rhea Silvia. Upon learning their royal origin, they killed their usurping uncle Amulius and restored their grandfather Numitor, rightful king of Alba Longa. Later, they founded Rome. Here, Acca Larentia is also called Faula or Fabula. She already had twelve sons and lived with them in a hut on the Cermalus. After Faustulus’s death, she adopted Romulus as an Arval Brother (Fratres Arvales), replacing a deceased son.

Representation of the lupercal: Romulus and Remus fed by the she-wolf, Lupa, surrounded by representations of the Tiber and the Palatine. Panel from an altar dedicated to the divine couple of Mars and Venus. Marble, Roman artwork of the end of the reign of Trajan (98-117 CE), later re-used under the Hadrianic era (117-132 CE) as a base for a statue of Silvan. From the portico of the Piazzale dei Corporazioni in Ostia Antica. Shown in museum of Palazzo Massimo alle Terme (Rome).

Acca became wealthy—either through prostitution [Cato, Origines Fr. I, 23 in Macrobius, Saturnalia I, 10, 16] or by marrying Tarutius, a rich Etruscan farmer [Licinius Macer Fr. 1 in Macrobius I, 10, 17]—and bequeathed her lands to Romulus, who passed them to the Roman people. In gratitude, the people instituted annual public honors at her tomb: the Larentalia.

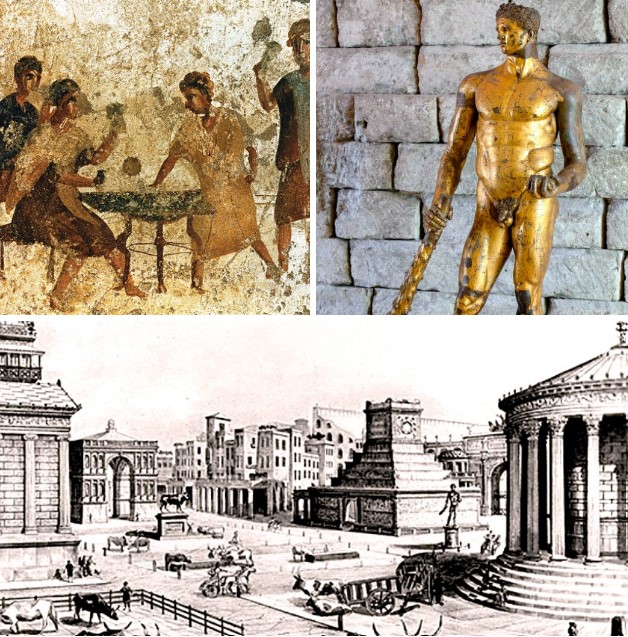

Roman fresco of dice players (Tavern of Mercury, Pompeii) · Gilded bronze statue of Hercules (2nd c. CE, Capitoline Museums), found in the Forum Boarium · Graphic reconstruction of the Forum Boarium: Right: Ara Maxima, statue and Temple of Hercules.

Second Tradition (7th century BCE) places Acca Larentia later, under King Ancus Marcius. The aedituus (temple guardian) of Hercules’ temple, bored on a festive evening, challenged the god to dice—staking a lavish dinner and a beautiful woman. He threw dice for himself and Hercules. The god won, so theaedituus prepared a sumptuous feast on the altar fire and summoned Acca Larentia, a famous prostitute. She slept in the temple, where Hercules appeared in a dream and coupled with her. The next day, she met a wealthy young Etruscan who asked her to be his lover. Recalling Hercules’ promise of reward, she accepted. When the Etruscan died, she inherited his wealth and later bequeathed it to Rome. King Ancus Marcius established her public cult [Plutarch, Romulus V; Roman Questions 35; Macrobius I, 10, 12–15; Tertullian II, 10; Augustine, City of God VI, 7].

Dice-throwing was a widespread divinatory rite of likely Eastern origin; the “feast” mirrors the iconography and cult of the Italic Hercules (banqueting as Epitrapezios); and the “divine-prostitute union” is a clear hierogamy (sacred marriage), reflecting Eastern-inspired sacred prostitution common in archaic Italy.

Here, the god won, and the guardian paid: he brought Hercules a feast and Acca Larentia. After their night together, Hercules promised her a good marriage. She married the wealthy farmer Tarutius and inherited his estate. She then willed it to Rome on condition of an annual public cult at her tomb—granted by Ancus Marcius.

This later myth tightly links Acca Larentia to the Hercules of the Ara Maxima, transforming the ancient Velabrum deity into a robilissimum scortum (“most notorious harlot”), whose profession centered on the Forum Boarium.

Both versions express a transition from negative to positive:

• Acca Larentia evolves from a shepherd’s wife to a wealthy farmer’s spouse (pastoralism → agriculture).

• She transforms from prostitute to revered matron (pre-civilized → civilized marriage).

• Calendrically, the Larentalia marked a definitive exit from primordiality (Saturnalia) into Jupiter’s reign—it was also a “Feast of Jupiter.”

The Vestal Virgins by Louis Hector Leroux (1829-1900)

Both traditions conclude identically: Rome inherits Acca Larentia’s lands. Closing December’s festivals echoed the idea of Rome’s territorial inheritance, paralleling the month’s first festival honoring Gaia Taracia. This Vestal received great honors for donating the campus Tiberinus, (Field of Mars) to Rome. Aulus Gellius explicitly pairs Acca Larentia and Gaia Taracia (7, 7, 1). The similarity between Gaia’s epithet Taracia and Acca’s husband Tarutius may also be significant.

Thus, behind Acca Larentia and her legends lies an ancient Goddess, whose cult likely dates to Rome’s earliest phases.

Largo Romolo e Remo 2, (Rome)