Abano Terme: Eternal Sanctuary of Healing Waters

Padua, Italy

Nestled in northeastern Italy, approximately 50 kilometers from Venice, Abano is a thermal resort gracefully unfolding at the foothills of the Euganean Hills. This dormant volcanic zone, which still retains pockets of intense geothermal heat, is renowned for its abundant thermal springs—celebrated for their therapeutic properties since antiquity.

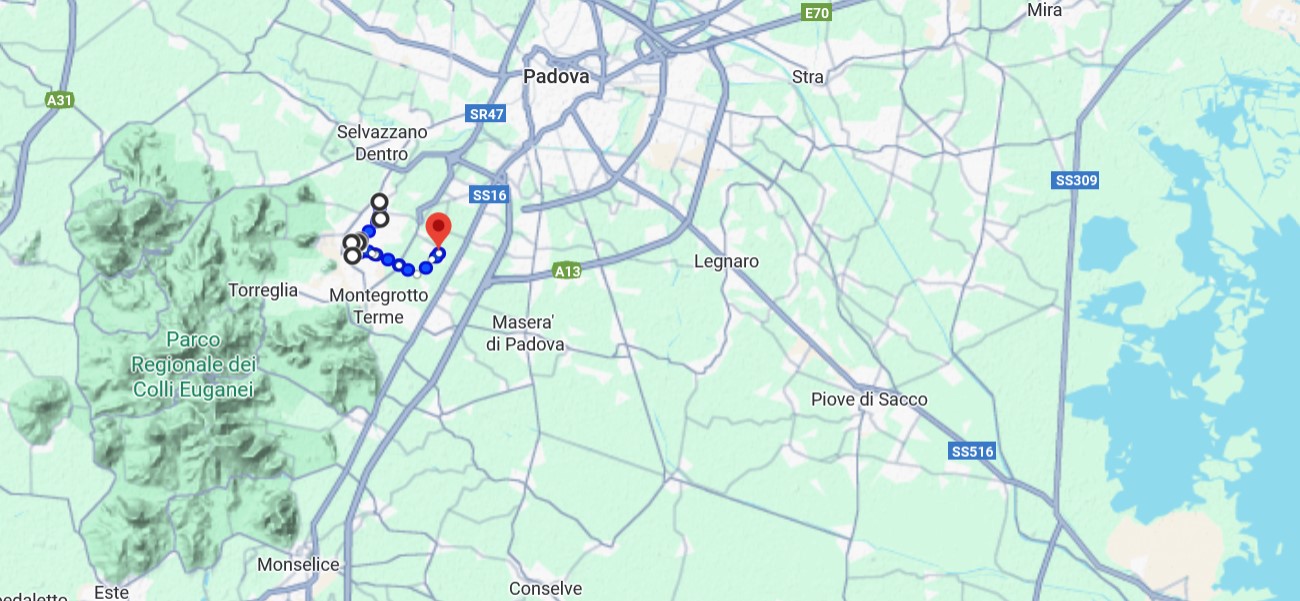

Abano Terme’s Location and View of the Euganean Hills

Archaeological evidence suggests Abano’s origins trace back to the 9th century BCE (Iron Age), when local tribes used natural thermal springs for rituals and healing. Lacking scientific knowledge, ancient peoples attributed the springs’ benefits to divine intervention.

Male Statue from Montegrotto Terme, Aponus (18th-century discovery)

An 18th-century find in Montegrotto Terme revealed a statue depicting a water deity (late 2nd century CE, now at Venice’s National Archaeological Museum).

The name Abano likely derives from the Latin Aponus—god of thermal waters, later equated with Apollo as a bestower of health. The root ap- (Indo-European for "water") evolved into Aquae Aponi (Greek: à ponos, "pain reliever"), meaning "waters of repose." The ancient baths occupied a vast area on the eastern slopes of hills formed 34 million years ago by Po Valley floods and localized volcanism. This geology fostered warm thermal-mineral springs, creating a landscape dotted with natural hot springs collected in small lakes or steaming pools, emitting a pungent sulfur scent. Key springs include Monte Irone (hottest), Montegrotto, Montortone, Battaglia, and San Pietro Montagnone.

These waters—reputed to cure muscle, joint, and skin ailments—were paired with ash-gray muds (44–75°C), transported widely despite their unpleasant odor.

Mud Curing Reservoir

The springs attracted the Euganei people (Latin: Euganei), who inhabited northeastern Italy between the Eastern Alps and the Adriatic. They lived in small hilltop communities, dwelling in stilt houses along warm lakes east of the Euganean Hills. They traded with Greek merchants sailing the Adriatic and Po River networks. When the Veneti arrived from Illyria (9th–8th century BCE), the Euganei retreated to the rugged hills.

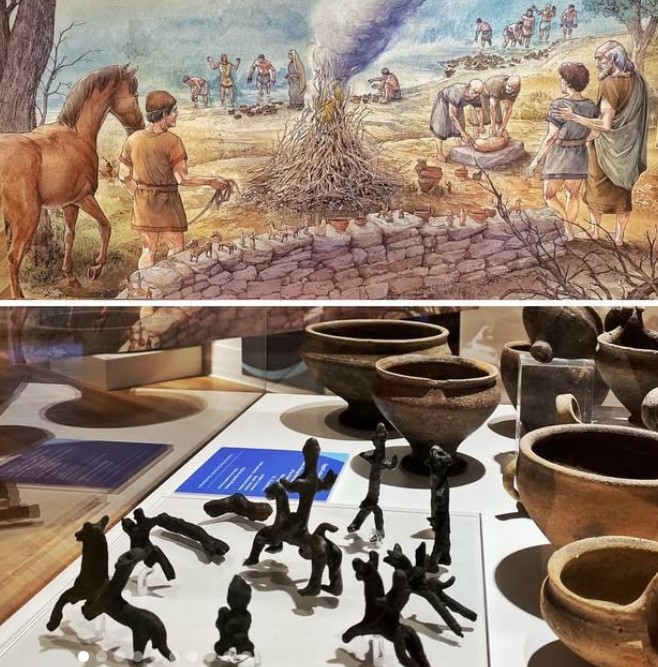

The Veneti cultivated the land, driving cultural and economic prosperity. Skilled farmers, famed horse breeders, and artisans, they elevated the region’s status. Bronze horse miniatures—votive offerings to the thermal lake deities—symbolized their gratitude. By the 8th century BCE, locals and pilgrims gathered at a circular sacred lake (3 km wide) to perform health rituals, leaving pottery, bronzes, and offerings on its shores.

Reconstruction of a 7th-Century BCE Lakeside Sanctuary and Votive objects displayed at Montegrotto’s Museum of Ancient Thermalism and Territory.

Despite marshlands and dense forests, a settlement named Aponus emerged by the 7th century BCE. All social classes journeyed here to immerse in the healing waters, offering precious gifts—vessels or anatomical replicas of cured body parts—to patron deities. Epigraphic texts confirm the sacred status of these springs.

From the late 3rd century BCE, the Veneti allied with Rome against Celtic incursions. Road networks and trade transformed Venetic life by the 2nd–1st century BCE.

Map of Euganean Hills Highlighting Roman-Era Sites

Roman artifacts in Abano Terme are sparse. Urban traces cluster along a 2-km axis (Via Battisti to Via Marzia), while rural ruins lie at Giarre (a 1st-century BCE farmstead). Evidence points to elite residences linked to thermal resources, but no public buildings. The settlement likely developed as Padua’s suburb between the late 1st century BCE and early 1st century CE.

Excavations revealed:

• Northern sector: Roman housing and a necropolis (Caesarean to 4th century CE).

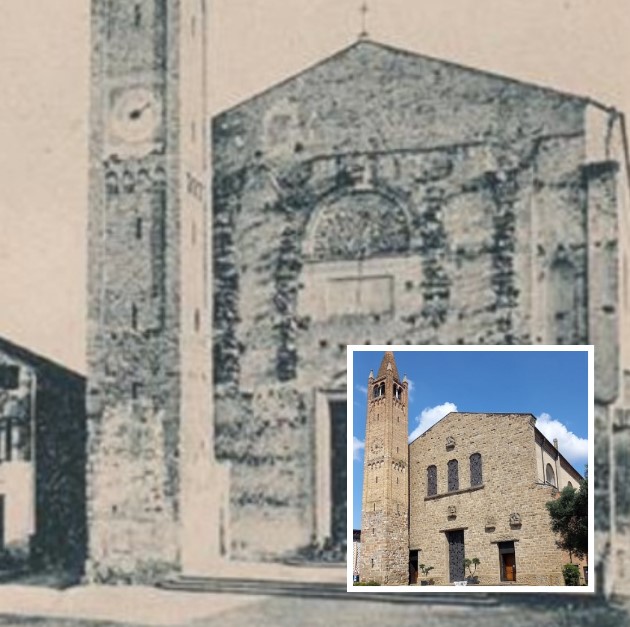

• San Lorenzo Cathedral site (Duomo): Paleo-Christian chapel, necropolis (1st–4th century CE), cobbled road, and aqueduct remnants. Though the current cathedral dates to the late 18th century, Christian worship here began by the 10th century. Reused 1st–2nd century CE materials suggest local origins.

The Cathedral Before 19th-Century Renovation

Key artifacts include:

• Coins from Tiberius to Constantine.

• A 1st-century CE boundary stone inscribed "Q(uinti) Crispi / iter / privatu / m."

• A fragmented funerary inscription of the Coelia family (1st century CE).

• A bronze medallion of Lucius Verus (166 CE).

Near Via Appia-Monterosso, a 1st-century CE necropolis was found. Around Parco Morosini, discoveries include:

• Roman and Julio-Claudian necropolises.

• Road and aqueduct ruins.

• A late 1st-century BCE emporium.

• Residential buildings (Roman/early Imperial eras).

• Funerary items (1st century CE and 3rd–2nd century BCE).

Roman Golden Age (1st Century BCE–4th Century CE)

Romans flocked to public thermae or private villas for restorative baths. Latin writers immortalized the site: Martial praised it; Pliny the Elder studied it; physician Aurelian prescribed it; Claudian poetically dubbed it Aquae Patavinorum ("Waters of Padua"). Livy, Suetonius, and Cassiodorus also documented it. Claudian noted: "Here, the suffering regain lost strength and return to health." Martial claimed poets Gaius Valerius Flaccus (Argonautica) and Arruntius Stella were born here.

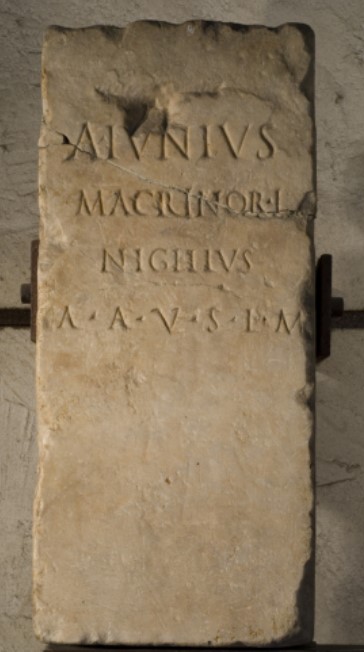

Quadrangular Sacred Stele (1st–2nd Century CE). Inscription: "A(ulus) Iunius / Macrinor(um) l(ibertus) / Nigellus / A(quis) A(ponis) v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito)" (Maffeian Lapidary Museum, Verona).

Under Imperial Rome, Abano peaked: Suetonius recorded Tiberius consulting Aponus’ oracle before war in Illyria. After a favorable prophecy, he cast golden dice into the spring. Padua became a Roman municipium, and local nobility emulated Roman thermal culture.

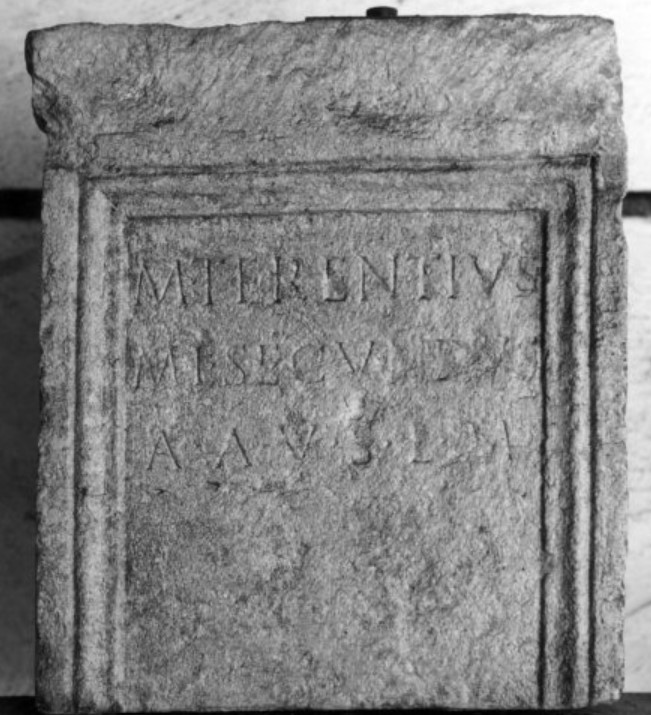

Framed Rectangular Altar (1st Century CE). Inscription: "M(arcus) Terentius / M(arcus) L(ucius) Secundus / A(quis) A(ponis) v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito)" (Maffeian Museum).

Were plunged in sorrow — yet rebuked the tear,

For yet they knew not of the fatal day.

Thus on Euganean hills where sulphurous fumes

Disclose the rise of Aponus from earth ...

—Lucan, Pharsalia 7.220 (ca. 65 CE)

1st-century CE excavations confirm a temple to Aponus on Montirone Hill and a nearby pottery emporium for therapeutic water vessels.

Endurance Through Ages

Thermal activity persisted through the 5th century CE. Despite the Empire’s collapse, the springs remained sought for healing—not leisure. Christianity upheld their medicinal value.

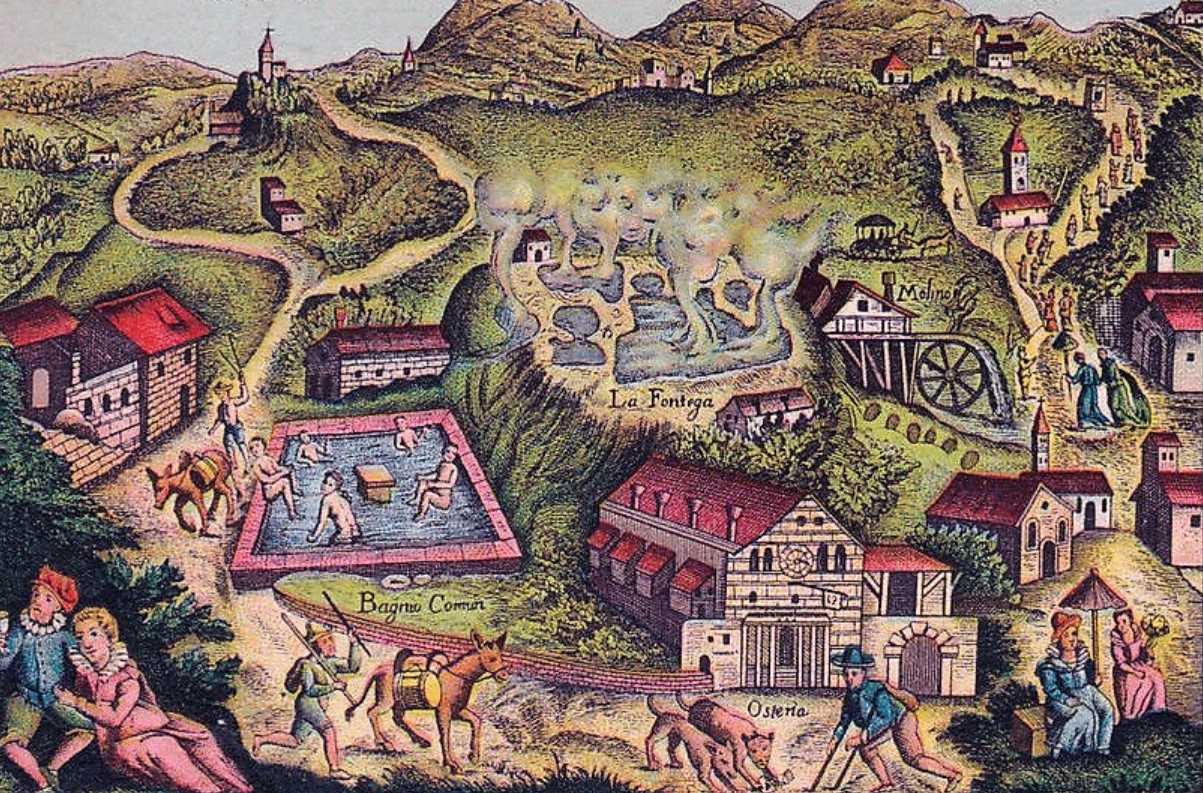

Abano Terme by Domenico Vandelli (1761)

Medieval monasteries revived thermalism, establishing health centers. Renaissance elites, including Venetian doges, frequented them. Today, Abano Terme—10 km southwest of Padua—is the Euganean thermal district’s heart. Each major hotel taps its own well, sustaining an unbroken legacy of healing.

Via Matteotti, 35031 Abano Terme (Padova)